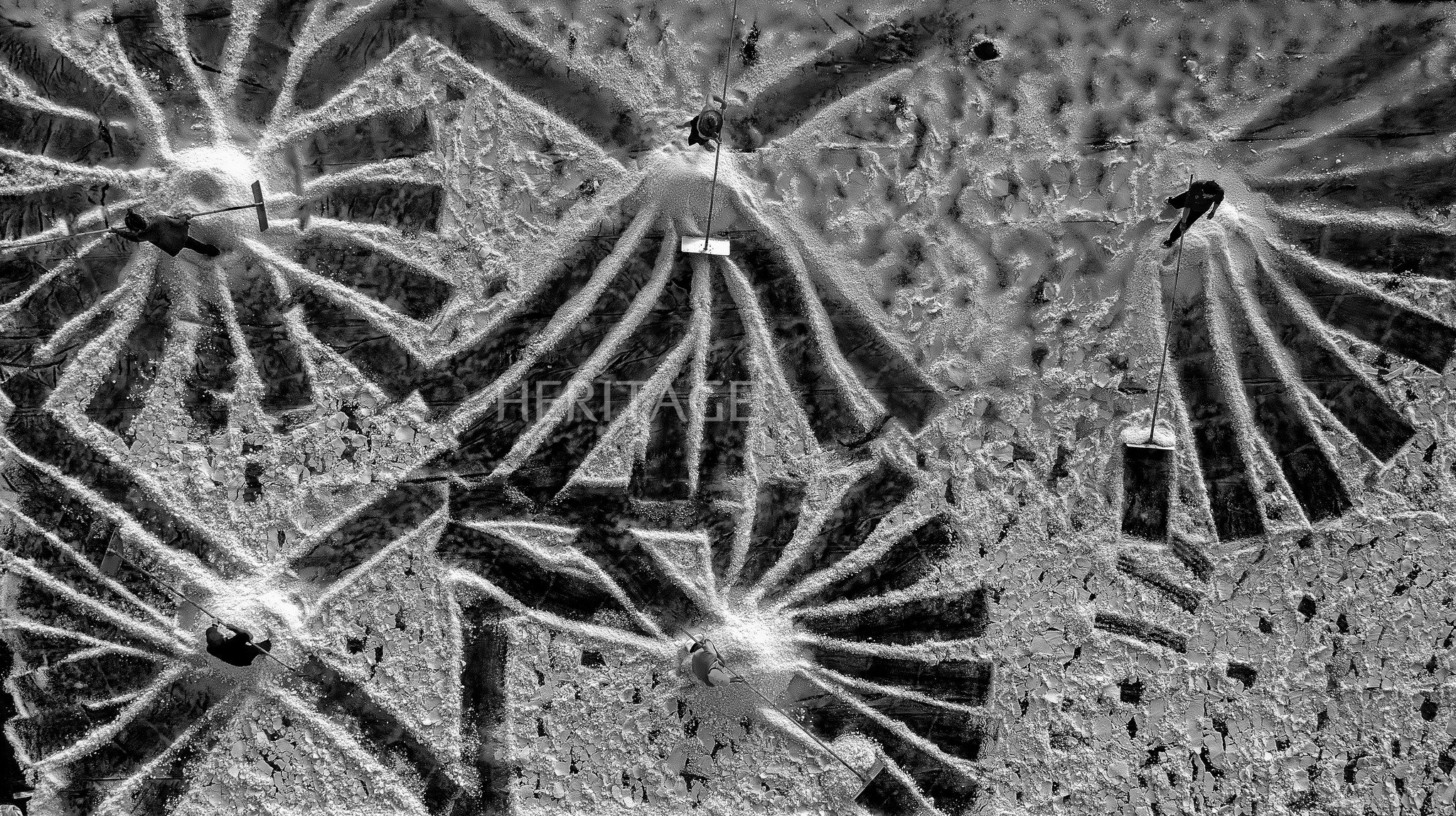

After financial preparations, dredgers, and field surveys, in 1901, France proceeded to dig the Xa No dredge canal.

A corner of Xa No canal today.

This was the initiative of two powerful French landowners, Duval and Guery, in exploiting the vast wilderness between the two provinces of Can Tho and Rach Gia. Not only for agricultural benefits, the French also had a vision: With this canal, a strategic waterway would connect to the Cai Lon River, to the West Sea; contributing to breaking the isolation of the Rach Gia region from the six provinces of Nam Ky.

The canal digging was carried out by the French company Montvenoux, using four dredgers named Loire, Nantes, My Tho 1 and My Tho 2. Each dredger had 350 horsepower, each large bucket could scoop up 375 liters, and blew mud up to 60 meters away.

Because the canal was dug by machinery from a mud scoop mounted on a barge (Vietnamese people mispronounce it as xang), this canal was called xang canal. As for the name Xa No, because this is the starting point of the canal on the Can Tho side. The excavator cut across Xa No canal, so this project was also named Xa No canal, even though the canal ran as far as Vi Thanh and Hoa Luu.

Learning in detail how to dig the Xa No canal, with technical parameters, we can see the scale and the work to be done is quite massive; but extremely difficult for a top-notch irrigation project in the South, comparable to the Saigon - My Tho railway project at that time.

The canal has a total length of about 45km, 12km on the Can Tho side and 33km on the Rach Gia side, following a straight water line without any curves. The canal is dug according to the following specifications: 2.5-9 meters deep, over 60 meters wide at the mouth, and 40 meters at the bottom.

In just 3 years, Xa No canal was completed, costing up to 3,680,000 French quan. The inauguration ceremony took place at the Vam Xang location on the Can Tho side of the canal, with the attendance of the Governor General of Indochina and many local officials.

This is a strategic project, part of the French colonialists' large-scale exploitation plan, on a large area of land between Can Tho and Rach Gia. Therefore, it has a strong impact on the economic and social development of this land that has long been dormant. In other words, because it was previously only exploited manually, it was difficult to progress quickly. Over a long period of time, the land reclamation from the Gia Long period to the Tu Duc period has not progressed much. It was only when science and technology were applied and mechanical power was developed that this land truly changed!

The canal section on the Can Tho side starts from the Vam Xang intersection of Can Tho canal; the end of the canal is at the border of Nhon Nghia village (present-day Bay Ngan area). From here, the excavation of the land on the Rach Gia side continues to the Vam Xang - Hoa Luu location adjacent to Cai Tu canal (a branch of Cai Lon river).

The canal section on the Can Tho side was easier to construct, because it was near many branches of the canal. Moreover, at this time, the Phong Dien and Cai Rang areas were prosperous, with favorable logistical conditions for canal digging activities. Meanwhile, on the Rach Gia side, there were wild forests all around, with flooding in the rainy season and dry fields and burnt grass in the dry season, and there were also many wild animals. At the time of canal digging: from the Mot Ngan to Muoi Bon Ngan areas, there were almost no residents, no villages, hamlets... In this area, there were only wild forest lands belonging to the end of Nhon Nghia village (Can Tho) extending to Vi Thuy and Vi Thanh villages; including the land of Hoa Luu village (Rach Gia). The remaining population lived scatteredly, along the natural banks of the Tram Cua, Cai Nhum, Cai Nhuc canals, etc.

In the first years after the canal was completed, before much exploitation could be done, there were two big storms in the Year of the Dragon (1904) and floods and droughts (1905), so the situation was not very optimistic. After that, many powerful French and Vietnamese landlords began to requisition and seize land from the direction of Can Tho, gradually encroaching on Rach Gia.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the potential for agricultural development in the Vi Thanh, Vi Thuy, and Hoa Luu regions was awakened, showing the clear effectiveness of digging the Xa No canal. Specifically, many Western and Vietnamese fields were formed in the style of "Tay Be" fields, namely the French landowner named Alber Gressier (also known as Tay Be fields, Ong Kho fields) in Bay Ngan. This landowner exploited the land by: Every 1,000 meters, he dug a large horizontal canal, every 500 meters, he dug a small canal to drain waterlogging and remove alum from the land on both sides of the Xa No canal. Therefore, there were canal names in numbers: One Thousand, Three Thousand, Four Thousand and a Half, Seven Thousand, Fourteen Thousand... Why didn't they continue digging the horizontal canals towards Vi Thanh when they reached the Fourteen Thousand canal? Because this area does not belong to Tay Be field, there are many natural rivers and canals such as: Nang Chang, Tram Cua, Ba Doi, Cai Nhum,... At the same time, thanks to the fresh water of Xa No canal, many cajuput forests in Hoa Luu, Vi Thanh were gradually cleared for farming and cultivation.

To encourage, the French government also issued many policies on land reclamation and management such as: Anyone who reclaims more than 10 acres of land will be exempted from taxes for 5 consecutive years; in a land owned by a French person exploiting 400 acres or more, they are allowed to employ 80 tenant farmers, and can apply to establish a new village. However, the French government also stipulated: Reclaimed land cannot be adjacent to canals or ditches more than 1/4 of the land's perimeter. The reclamation area of more than 1,000 acres is decided by the Governor-General of Indochina.

The remarkable achievement of the canal digging was: the first application of the model of agricultural production concentration in the form of land ownership, from a few dozen, a few hundred to a few tens of thousands of acres (like Ong Kho - Bay Ngan land). Accordingly, applying scientific and technical advances such as: closed irrigation, through building sluices, stone dams (still have evidence today). Regarding traction, many buffaloes were purchased to plow and pull carts during harvest. Some documents say that in Bay Ngan land, plows were experimented with, including harrows, seedling sowing machines,... But the results were not very positive.

With the efforts to exploit the effects of the Xa No canal, the number of landowners and wealthy people in the Vi Thanh, Vi Thuy, and Hoa Luu areas increased rapidly, with famous figures emerging who owned a lot of land. In 1912, according to statistics from Rach Gia province, the French owned the most land with 26,121 acres owned by 23 landowners. By the 30s and 40s of the last century, in Hoa Luu village alone, the number of Vietnamese landowners increased rapidly: Tran Kim Yen (Sau Yen): Had land from Di Han intersection to Kinh Nam, running 5km along the Nuoc Duc river, with 5 cajuput forest holes hundreds of acres wide.

In addition, there are many other landowners in Hoa Luu who do not know the exact amount of land such as: Hoi Dong Ho, Tran Phu Quoi, Nguyen Viet Lien, Tran Giac, Ly Tan Loi (Ca Loi), Boi Bang,... and dozens of other powerful landowners (rich farmers).

The land expanded, fresh water flooded, farming methods also gradually changed, the main farming techniques were still weeding, planting rice, harvesting, threshing, and cleaning. The average yield at that time was from 10-12 bushels/cong. There was an individual who cultivated 3 cong of land and achieved nearly 50 bushels of rice. From 1910, traders and rice millers bought rice from Rach Gia area (Go Quao, Long My, Vi Thanh, Vi Thuy, Hoa Luu) along Xa No canal, transported it to Cai Rang market, brought it to mills, and then transferred it to Cho Lon for export.

The land reclamation work quickly brought results, contributing to Rach Gia province rising to the top position in the South in rice production, with an area of 319,960 hectares and an output of 394,900 tons in 1930.

CLEAN TASTE

Source link

Comment (0)