Vanbleu's bright yellow jacket stands out against the waves, his draft horse pulling a rope along the sand, causing vibrations that cause shrimp to jump into the taut net.

Gunther Vanbleu, 49, a Belgian shrimp fisherman with 10 years of experience, rides his horse Martha to pull a shrimp net during low tide in the coastal town of Oostduinkerke, Belgium, on October 24, 2023. Photo: REUTERS

The coastal village of Oostduinkerke is the last place in the world where crawfish fishing is still practiced – a centuries-old tradition now recognised by UNESCO.

Fishermen's proximity to coastal waters has made them firsthand witnesses to how climate change is altering the North Sea's ecosystems.

“We catch less shrimp than we used to,” Vanbleu told Reuters. “But we also have a lot of weeds and animals that you never saw here before, which come from the Atlantic when the water warms up.” Weevers are small, venomous fish that tend to burrow into the sand using only their eyes.

According to NASA, the ocean has absorbed 90% of the global warming caused by humans over the past few decades. In the North Sea, surface temperatures have increased by about 0.3 degrees Celsius per decade since 1991.

That rise in temperatures has disrupted traditional seasons for the horseback fishing community.

“The fishing season ends when we see the first snow; it ends in December. Now we don’t see any snow,” said fisherman Eddy D’Hulster.

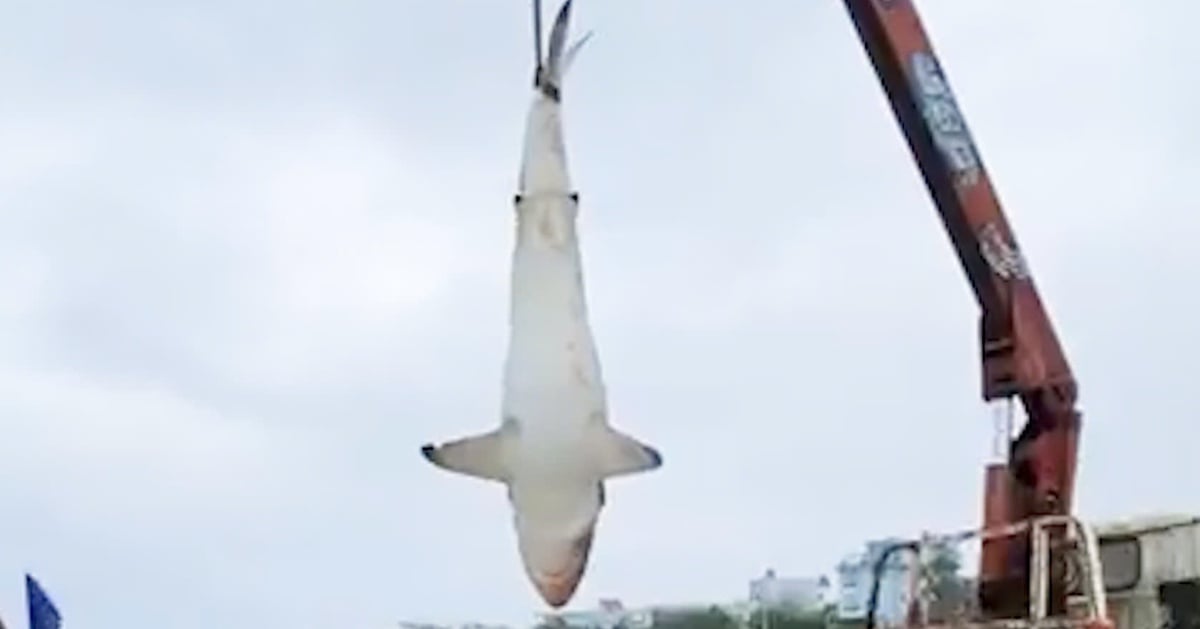

While shrimp populations fluctuate during short-term changes like heat waves, fishermen and scientists report increases in smaller fish and squid populations, traditionally found further south but which have moved north into the warming waters of Belgium.

“For some species, we saw higher abundance, such as cuttlefish and squid, like cuttlefish,” said Ilias Semmouri, a marine ecologist at Ghent University.

North Sea cod populations have declined sharply since the 1980s, a cause scientists blame on rising sea temperatures and overfishing.

Climate change is causing unpredictable changes in fish stocks, making it more difficult to set catch quotas to sustainably manage marine populations, said Hans Polet, scientific director of ILVO, the Belgian Flanders fisheries research institute.

“Nature is no longer responding the way we are used to,” Polet said. “Chaos is coming into the system… I am worried, I am really worried.”

Mai Van (according to Reuters, CNA)

Source

Comment (0)