A massive reconstruction effort is still underway a year later, but many questions remain about the future of devastated areas.

What exactly happened?

The February 6, 2023, earthquake struck shortly after 4 a.m. local time and lasted 85 seconds. It was followed by more than 570 aftershocks within 24 hours — including a magnitude 7.5 quake north of the original epicenter in Türkiye's Kahramanmaras province.

According to the latest figures released by Türkiye's Environment and Urbanization Minister Mehmet Ozhaseki on Friday, some 680,000 homes collapsed or were so badly damaged that they were uninhabitable, leaving hundreds of thousands of people in need of shelter.

The disaster sparked a massive international rescue and aid operation involving dozens of countries and organizations. Initially, the worst-hit areas were difficult to reach, forcing people to dig through the rubble with what tools they could.

Rescue efforts in both countries have been hampered by a lack of manpower and equipment. Damaged roads and airports as well as bad weather have also hampered the arrival of rescuers and aid.

The rubble of buildings destroyed by an earthquake in the city of Antakya, Türkiye on January 11, 2024. Photo: AP

In Syria's northwestern Idlib province, the White Helmets rescue group blamed the international community for delays, while Turkish authorities faced criticism for a slow response that left many people waiting days for help.

Aid to opposition-held Idlib was initially limited to a border crossing between Türkiye and Syria, with the first aid shipment after the earthquake taking three days to reach survivors.

While television images of survivors being pulled from the rubble have raised hopes, the death toll is still rising. The Turkish Interior Ministry said on Friday that the final death toll in Türkiye had reached 53,537. The earthquake displaced about 3 million people and 11 provinces in Turkey were declared emergency zones.

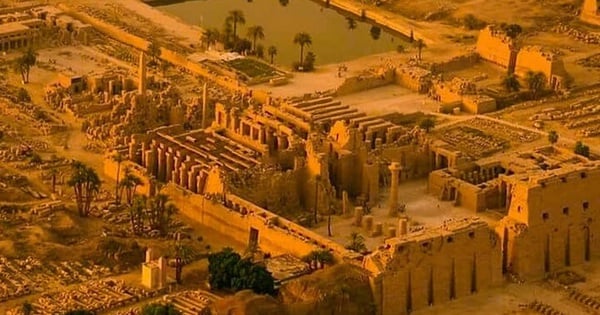

In Syria, the United Nations says 6,000 people have been killed, mostly in Idlib. Other estimates put the figure higher. The quake came after more than a decade of civil war that has left Syria’s infrastructure severely damaged. Some of the areas hardest hit by the quake were also some of the areas hardest hit by the conflict, including the city of Aleppo.

The World Bank estimates the damage in Türkiye at $34.2 billion and in Syria at $5.1 billion. But the cost of rebuilding and the impact on the economy are much larger—at least $100 billion in Türkiye’s case.

Continuous geological risk

Türkiye sits on several fault lines, making it one of the most earthquake-prone countries in the world. The East Anatolian Fault System, where the disaster occurred, lies near where the Anatolian, Arabian and African tectonic plates meet.

In 2020, the country suffered several major earthquakes, including the most recent major one on the East Anatolian Fault – a magnitude 6.7 quake in the city of Elazig that killed 41 people.

The East Anatolian Fault last saw an earthquake of magnitude 7 or greater in 1822, when at least 10,000 people were killed in Aleppo, Syria.

Why such great damage?

Türkiye strengthened building regulations after the 1999 Istanbul earthquake but experts say lax enforcement, poor planning and irregularities since then made the 2023 disaster worse.

The use of poor quality materials and lack of proper inspection during Türkiye's construction boom in recent years have made the problem worse, experts say.

In Hatay, the hardest-hit province, many settlements are built on risky alluvial soil. A government amnesty for shoddy construction, which allows violators to pay fines instead of demolishing or repairing dangerous buildings, is also a factor.

Delays in search and rescue operations also led to higher death tolls, critics say.

Humanitarian aid shrinks

In the weeks after the earthquake, humanitarian aid began pouring into Syria, and a United Nations appeal raised nearly $387 million in pledges.

But months later, as other crises emerged, Syria’s priorities seemed to fall by the wayside. To this day, humanitarian organizations struggle to bring the world’s attention back to the war-torn country as they face donor fatigue and shrinking budgets.

A man displays flowers for sale next to the ruins of destroyed buildings in downtown Antakya, Türkiye on January 11, 2024. AP Photo

Last June, an annual international donor conference in Brussels for Syria met with mixed results, and the following month the World Food Programme (WFP) announced it would cut aid to the war-torn country. In January, the WFP ended its main food assistance programme for Syria.

In many places, rubble remains where it fell as people struggle to survive in tents and prefabricated containers, a year after the quake. About 4 million people are relying on humanitarian aid amid rising violence in northern Syria.

Mai Anh (according to AP)

Source

Comment (0)