The global housing market is caught in a dilemma, with borrowing costs continuing to hit record highs and limited supply pushing up prices. In many regions, the dream of owning a home has slipped out of reach for many, while those fortunate enough to own a home are struggling to pay their debts.

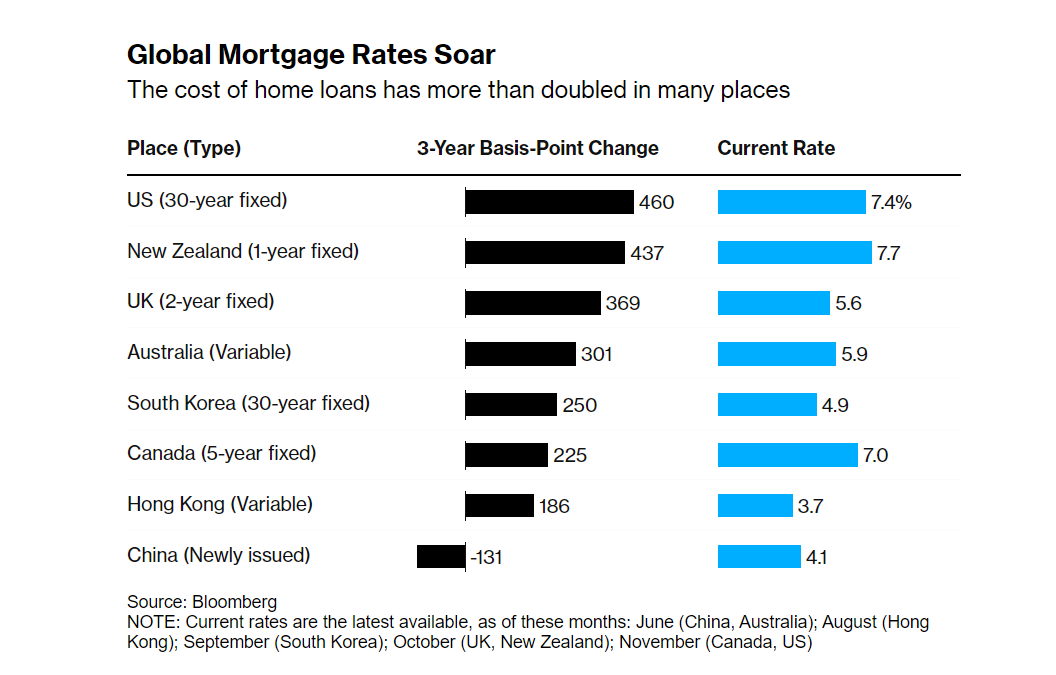

In the United States, where 30-year mortgages are common, the housing market has all but frozen as buyers have lost interest in making purchases as interest rates have risen. In New Zealand and Canada, home prices have never fallen below what buyers consider reasonable.

From the UK to South Korea, financial hardship is growing for homebuyers. And in many other places around the globe, high borrowing costs are making building and owning a new home more expensive than ever.

People around the world are finding it harder to buy or own homes. (Photo: Bloomberg)

The severity of the housing market downturn will vary from country to country, but overall, the situation will have a negative impact on global economic growth as people have to pay more for housing, whether they own or rent.

And with homebuyers becoming more cautious, home ownership as a profitable investment channel, the foundation for building personal financial independence for many generations of people in many countries, has become less attractive. The only rare winners are long-term homeowners who have been lucky enough to make a profit when real estate values have increased or bought a house without the need for mortgage loans.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Analytics, predicts that the 30-year mortgage rate in the US, currently at 7.4%, will cool to an average of 5.5% over the next 10 years. However, this is still a relatively high interest rate compared to just 2.65% recorded at the beginning of 2021. More importantly, he believes that this trend will also occur in many other developed countries.

And there are other unpredictable variables. The ongoing conflict in the Middle East and China’s economic difficulties could slow global growth, reducing housing demand and pushing down home prices. Meanwhile, the commercial real estate segment has in fact become a “burden” for the market itself in many economies.

And even as inflation cools and monetary policy begins to loosen, the thought that borrowing costs will never fall as low as they did in the post-global financial crisis period may still linger in the minds of many.

Mortgage interest rates have increased sharply in many countries (Photo: Bloomberg).

"Freezing phase"

In the U.S., low inventory, rising home prices and rising mortgage rates have pushed home sales to their lowest level since 2010, according to the National Association of Realtors. In October, the number of home purchase contracts signed fell 4.1% from the previous month, the lowest in nearly a year.

The housing market is now at its most unaffordable in four decades, with costs taking up about 40 percent of a household's income, according to data from Intercontinental Exchange Inc.

But the worst is yet to come. In an October report, Goldman Sachs said the impact of rising mortgage rates would be felt most clearly in 2024. They estimated that home sales would fall to their lowest level since the early 1990s.

“We are, in a sense, at the beginning of a ‘frozen’ phase that is not going to melt anytime soon,” said Benjamin Keys, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Things will improve, but certainly not in the way people want,” predicts Niraj Shah, an economist at Bloomberg Economics. The global housing market is struggling on both ends (buyers and sellers), he said.

He predicts that home prices in developed countries will fall slowly rather than “collapse” because unemployment will not rise too sharply. But a home will still be out of reach for many. And those who buy when prices and interest rates are high will be forced to cut back on spending to pay off their debts, he added.

Count every penny

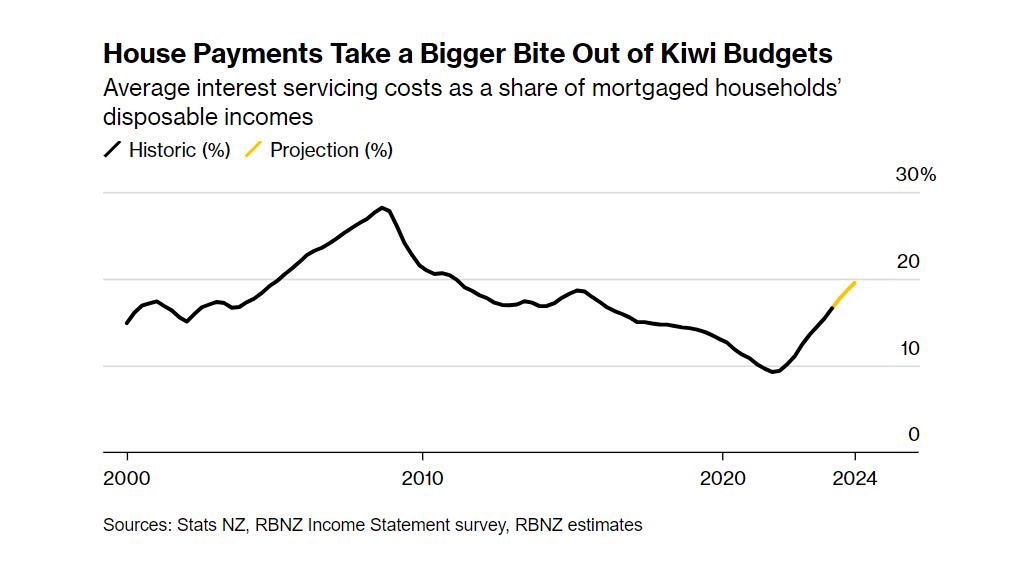

The situation is most acute in New Zealand, where the housing market has boomed during the pandemic, with house prices rising nearly 30% in 2021 alone. Twenty-five percent of all mortgages outstanding in the country were issued that year, and one-fifth of mortgage borrowers were first-time buyers, according to data from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ).

Mortgage rates in the South Pacific nation are typically fixed for less than three years, meaning a 525 basis point increase in the cash rate from October 2021 will make repayments even more difficult. The RBNZ estimates that Australians’ interest payments will rise from 9% of disposable income in 2021 to around 20% by mid-2024.

New Zealanders' home loan interest payments are expected to be up to one-fifth of their income (Photo: Bloomberg).

That drains the income of people like Aaron Rubin, who took out a NZ$1 million ($603,000) loan in 2021 to buy a four-bedroom house worth NZ$1.2 million. After moving to New Zealand from the United States eight years ago, he and his wife, Jessica, always thought buying a house in the coastal city of Nelson was the right decision to give their two children a stable life later on.

Initially, the couple were only paying around NZ$4,000 a month on the loan. But now that the interest-free period has ended, they are paying an additional NZ$2,400 a month.

“We didn’t even have enough money to go back to the States to visit relatives. Every penny had to be carefully considered,” said Rubin, now a software engineer. “It was time-consuming and stressful. Our lives were turned upside down.”

Still, he considers himself lucky to be able to afford the monthly interest payments. He said many of his friends are under much greater financial pressure.

Investors turn away

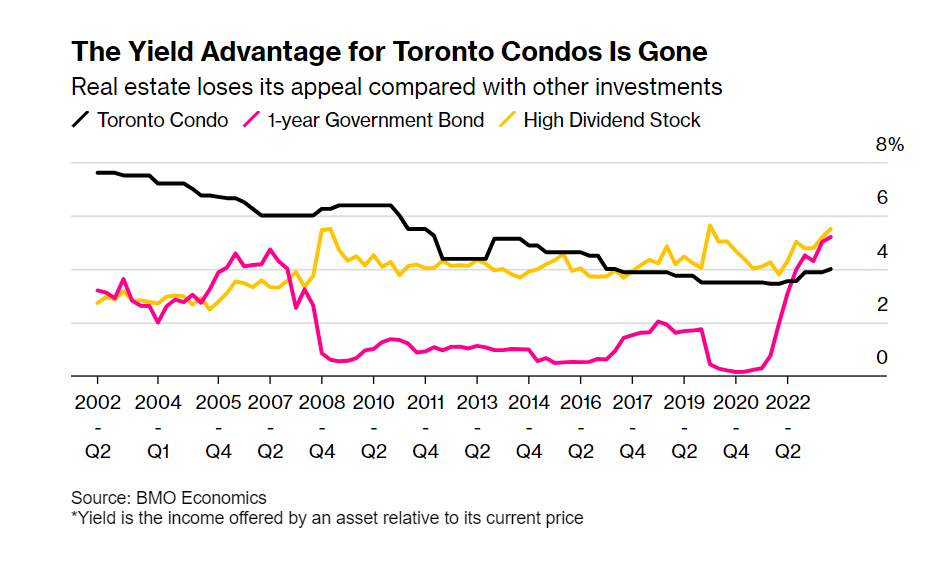

The boom in the past decade has turned real estate products into the leading profitable investment channel in countries such as New Zealand, Australia, and especially Canada, where tens of thousands of people quickly became F0 investors in the real estate market.

As of 2020, the number of apartments owned by investors who own at least one real estate product accounts for one-third of the total number of houses in the two most populous provinces of this North American country (Ontario and British Columbia).

But rising interest rates and bond yields have made that investment formula ineffective. Owning a condo in Toronto, Canada’s largest city, yields just 3.9% after expenses, well below the 5% yield on government bonds, according to research by the Bank of Montreal.

Buying a home is no longer an attractive investment channel in Canada (Photo: Bloomberg).

Investors’ willingness to buy real estate products before completion has been an important source of capital for developers over the past decade. And the lack of interest from customers has caused many projects to stagnate due to lack of capital.

Canada’s low housing supply is the reason why home prices have remained high despite the market’s struggles. And the slowdown in construction has only exacerbated the shortage.

A similar situation is occurring in Europe, where high interest rates and rising construction costs have left housing in short supply.

In Germany, building permit applications fell more than 27% in the first half of the year, while France saw a 28% drop in the first seven months. Meanwhile, construction in Sweden is only about a third of what is needed to meet overall market demand, which will keep house prices rising rather than cooling.

The impact of high inflation is also worth mentioning. In the UK, which has seen the fastest rise in living costs in decades, around 2 million people have switched to buy now pay later to make ends meet, according to the Money and Pensions Service. With more than 1 million homeowners facing higher mortgage payments this year, the financial strain is sure to be huge.

According to a recent KPMG report, around a quarter of UK mortgage-financed homebuyers are considering selling their homes and moving to cheaper housing options amid rising finance costs. Renters will also have to share some of the financial pressure with their landlords.

Karen Gregory, who lives in London, had no choice but to sell her existing home when her monthly mortgage payments more than tripled. The young couple with a young child who were renting their home would then have to find somewhere else to live or renegotiate their lease with a new landlord.

"We've had enough of rising interest rates," Gregory said.

Construction activity is sluggish amid rising interest rates, causing housing supply to remain scarce (Photo: Bloomberg).

Asia is no exception.

Homeowners are crying foul in South Korea, which has the highest household debt-to-GDP ratio among developed nations, at 157% if you include the nearly $800 billion in "jeonse" debt.

When participating in this system, the landlord will receive a deposit (called jeonse), equivalent to 1/2 of the apartment's value, at the beginning of the rental period, which usually lasts from 2 to 4 years.

As interest rates rise, jeonse becomes less attractive than monthly rent, reducing the amount of security deposits that landlords collect. Landlords often use new security deposits to pay off old leases that have expired, making it harder for them to meet their obligations.

The risk of apartment owners defaulting is forecast to remain high in 2024 as the number of contracts about to expire was signed at a time when house prices in Korea were escalating.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s housing market has been hit by China’s slowing growth, population displacement and high interest rates, which have slowed home price growth. Since the city’s currency is pegged to the US dollar, the monetary policy adopted by Hong Kong’s financial regulator must closely follow the Fed’s actions.

House prices in the city’s once most expensive areas have fallen to a six-year low, but no one is buying them. Construction companies are therefore forced to offer steep discounts while the government cuts registration fees to stimulate the market.

Housing prices in Hong Kong (China) have fallen but are still out of reach for many people (Photo: Bloomberg).

But unless interest rates are cut, the city’s housing market will not recover. House prices have risen so rapidly over the past decade that the dream of owning a home is out of reach for many. Sadly, the recent decline in home prices has not been strong enough to offset the rising cost of borrowing.

“Housing markets in many countries have been ‘partying’ for the past two decades, supported by record low interest rates and limited supply,” said Shah of Bloomberg Economics. “But the coming decade will be a painful one,” he warned.

Source

Comment (0)