More than 9,000 doctors have resigned in a row over the disparity in benefits between essential treatment departments and more profitable departments in the South Korean medical industry.

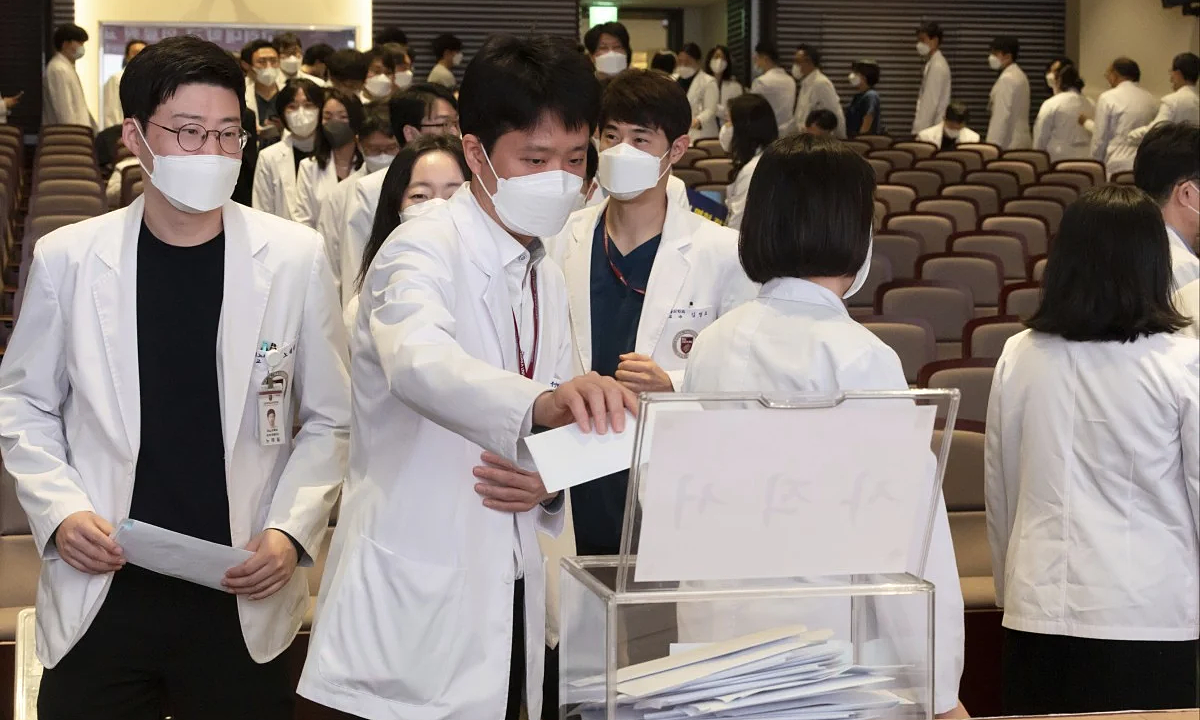

South Korean medical residents filed a collective resignation earlier this week to protest the government's proposed medical education reform program, which calls for increasing the enrollment quota for medical schools by 2,000 people per year from 2025.

More than 9,200 resident physicians, accounting for more than 70 percent of Korea's young medical staff, have applied for collective leave, with more than 7,800 leaving their workplaces. Nearly 12,000 medical students nationwide have also applied for leave, accounting for nearly 63 percent of all medical students in Korea.

The widespread strike has caused problems in the South Korean healthcare system. Many of the country's largest hospitals have had to reduce their operating capacity by 50%, refuse to accept patients or cancel surgeries, raising concerns that the healthcare system will be disrupted if the resident doctors' protest continues.

The South Korean Health Ministry raised the health alert to critical on the evening of February 22. The government asked doctors to return to work and called for dialogue with the government, but they showed no signs of backing down. The government also instructed hospital leaders to reject requests for leave from interns.

South Korean doctors protest in front of the presidential office in Seoul on February 22. Photo: Reuters

The South Korean government has launched a plan to reform the healthcare sector because the country has one of the lowest doctor-to-patient ratios in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In 2023, South Korea will have 2.2 doctors per 1,000 patients, lower than the OECD average.

It will also be the first time South Korea has increased its medical school enrollment quota in 27 years, in response to a rapidly aging society. South Korea is expected to face a shortage of 15,000 doctors by 2035, when seniors are expected to make up 30 percent of the population.

The government says its plan to increase medical school enrollment will partly address the shortage of doctors, promising an additional 2,000 medical graduates by 2031 after completing six years of study.

But contrary to the government's view, resident doctors say the country does not need more doctors because it already has enough, and that changing the policy would reduce the quality of national health care, arguing that the population is shrinking and that South Koreans have easy access to medical services. The average outpatient visit per person in the country is 14.7 times a year, higher than the OECD average.

Interns point out that one problem in the current Korean medical industry is the shortage of personnel and income disparity in essential but "unattractive" departments such as pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology.

They argue that doctors are not interested in these specialties because the services they provide are often cheaper than "sexy" specialties such as cosmetic surgery and dermatology, where fees are set by doctors rather than covered by health insurance. They cite the cost of childbirth as being much lower than the cost of a simple laser skin treatment, which has led many students to enroll in cosmetic surgery instead of obstetrics.

The South Korean government believes that low-cost essential departments will benefit from the new health insurance policy it announced earlier this month. Under the new policy, the insurance will provide financial support for pediatrics, intensive care, psychiatric, and infectious diseases departments based on the urgency, difficulty, and risk of treating a case.

But resident doctors stress that increasing medical school enrollment will not help fill staffing gaps in essential departments, but will only increase competition for "attractive" departments, especially in Seoul hospitals.

South Korean Prime Minister Han Duck-soo (in blue) visits doctors at the National Police Hospital in Seoul, February 21. Photo: AP

Last week’s strike was not the first time that South Korean doctors have protested against plans to increase medical school enrollment. During the Covid-19 pandemic, many resident doctors went on strike, forcing the government to back down.

Doctors also say the government needs to address their working conditions before considering increasing the number of medical staff. South Korean resident doctors often work 80-100 hours over five days a week, or 20 hours a day, leaving many feeling overwhelmed.

They argue that the situation can only be improved by recruiting more experienced doctors, not by increasing the number of students and new doctors. The Korean Medical Association (KMA), which represents the majority of doctors in the country, has also accused the plan to increase the medical school enrollment quota as a populist measure to strengthen the government's position ahead of the election.

Jeong Hyung-jun, policy director of the Korean Medical Activist Group, added that young doctors may be concerned that increasing the number of students will affect their social status, as having more doctors will increase competition in the market.

He said that in Western countries, public hospitals account for 50% of medical facilities, so doctors welcome having new colleagues, because the workload is reduced but income remains the same.

But in South Korea, many doctors open private clinics, where they set their own fees. Prices for private clinics would fall sharply if more doctors entered the market, hurting their incomes.

"That's why the so-called 'three-minute treatment' flourished, where doctors spend only three minutes on each patient to increase the number of visits to maximize profits," said Lee Ju-yul, a professor of medical management at Namseoul University.

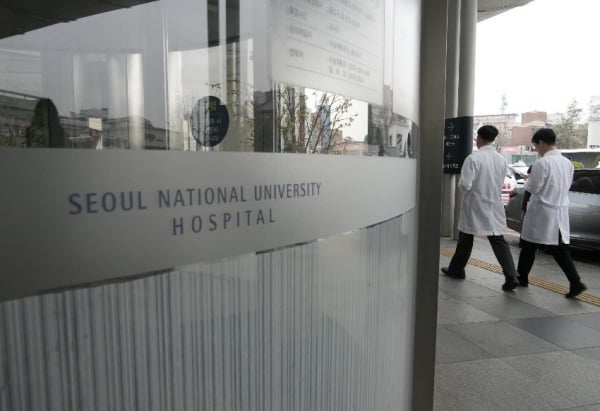

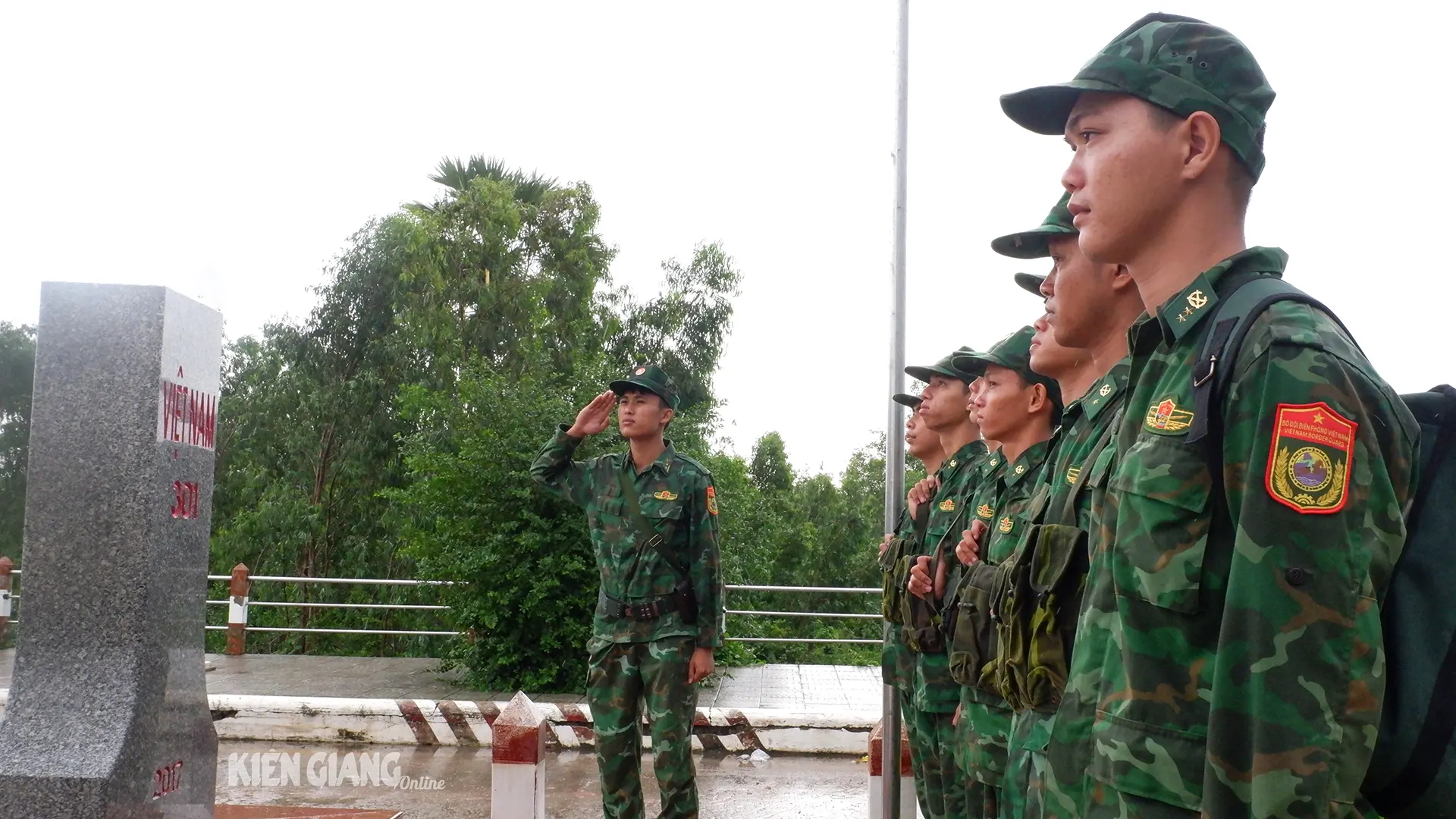

A doctor at a hospital in Seoul, South Korea on February 18. Photo: Yonhap

The South Korean public and many other medical organizations support the plan to increase medical school enrollment quotas. A survey by the Korean Medical Workers Union (KMHU) in late 2023 showed that nearly 90% of the public supported increasing medical school enrollment quotas, up nearly 20% from 2022.

But supporters also stress that plans to increase doctors will only be effective when accompanied by measures to improve the status of the public health system, acknowledging that the marketization of medicine is one of the main reasons why many specialties are less attractive.

"Even if we increase the training of thousands of doctors, there is no guarantee that they will enter essential departments or public hospitals," said the Korean Federation of Medical Rights Activists (KMFA).

Duc Trung (According to Korea Herald, People Dispatch )

Source link

Comment (0)