PV: The journey from a village school student to the top graduate of the Materials Science department of the top engineering school in France must have many special things?

- An interesting thing is that my journey is not a pre-planned one, but a series of opportunities.

I was born in the poor countryside of Can Loc, Ha Tinh. In terms of learning conditions or access to new fields and knowledge, it cannot be compared to big cities.

After graduating from secondary school in the village, I was lucky to pass the entrance exam to the specialized Math class of Vinh University High School for the Gifted. This was my first chance.

Later, when I delved deeper into the research, I realized that mathematics is not just dry numbers but a foundation for logical thinking to delve into physics, chemistry, programming, and simulation, which are closely related to the field of materials science that I pursue.

When choosing a major for the university entrance exam, I asked my father for advice. He is a person who has the habit of listening to the radio and always updating the news. "Materials science and nanotechnology will be the future", his orientation led to the decision to register for the entrance exam for Engineering Physics and Nanotechnology at the University of Technology (Vietnam National University, Hanoi).

To be honest, at that time I didn't really understand what this industry was. I just found "nano" to be new and interesting.

After 6 months of studying, I received a scholarship from Project 322 - a program of the Vietnamese Government to send students abroad for training using the State budget.

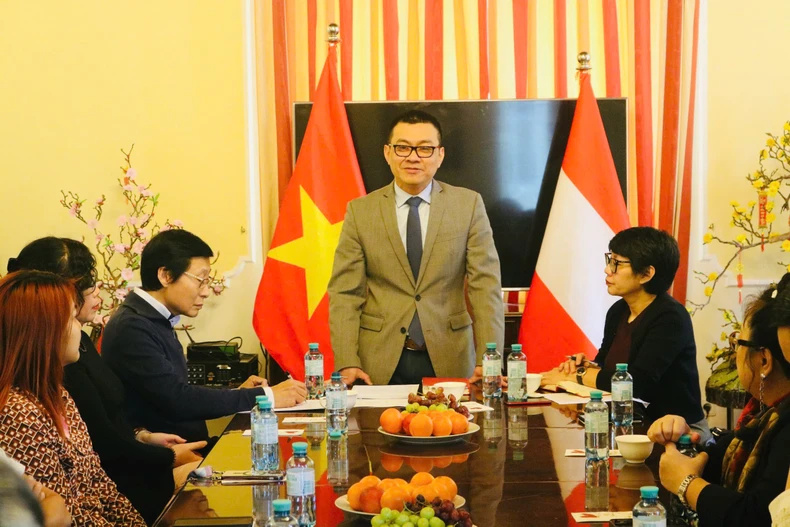

I was selected to study engineering at the National Institute of Applied Sciences in Lyon (INSA de Lyon) in France. My 9-year journey of pursuing knowledge in a foreign country began from there.

Is it surprising to learn that it was his father who introduced his son to a field that, even now, is still very new?

- My father is also the one who inspired me throughout my studies and important decisions later on.

He joined the army when he was 17-18 years old, participating in the resistance war against America.

After 1975, he had the opportunity to receive a scholarship to study in the former Soviet Union for 7 years. Although he really wanted to go, he had to put his dream aside to take care of his family. While fulfilling his duties as the eldest son, he also had to work hard to earn a living to support my four siblings and me to study.

However, he always inspires us with dedication.

"You can do any job, but don't care too much about material things, but have a spirit of dedication. If you can do something for your village or hometown, that's good." My father's simple advice is also our guiding principle on the journey ahead.

Receiving a scholarship to study in France, I was always aware that I had the responsibility to continue my father's unfinished dream. Those were the difficult but glorious years of my twenties.

Was studying abroad in France a "fate" as you call it, leading you to the path of scientific research?

- I was a good student, but I never thought I would become a researcher. For me, studying was simply doing my best within the framework of what was taught.

I don't have a clear concept of scientific research, and I don't have an idea of what it means to create new knowledge.

The turning point leading to the door of scientific research and then truly becoming a professional researcher was a 6-month internship in Belgium to graduate with a master's degree in science.

My internship was at IMEC (Interuniversity Microelectronics Centre, Belgium) - one of the leading nanotechnology research centres in Europe. This was a completely different environment from what I had experienced before.

IMEC has more than 2,000 researchers working on the most advanced technologies in semiconductors, microelectronics, nanosensors, new materials. What I used to read about in books is now a reality before my eyes.

Having studied in France, a very advanced country, I was still amazed by the scale and modern equipment system of this center.

I feel like a fish in water, the environment here gives me a lot of inspiration to pursue a career in scientific research, when working with very intelligent, diligent and professional people.

After finishing my internship, I returned to France and decided to do a PhD at the Materials-Physics Laboratory (LMGP), part of CNRS & Grenoble Polytechnic School, pursuing the development of spatially-typed atomic layer deposition (SALD) technology.

In short, it is the technology of manufacturing nano-thin film materials with atomic-level control. It is like wearing many layers of clothes and each layer is a layer at the atomic level.

This technology is like a universal key to open up applications in many different fields.

Living in a place that is still considered a "paradise" for scientific researchers and certainly comes with attractive job opportunities, why did you decide to return to Vietnam after nearly a decade in Europe?

- For me, there is no hesitation between returning or staying. "Do something for the village and homeland", my father's advice is something I always keep in mind.

Therefore, from the moment I set foot in France, I always assumed that I would return to Vietnam. The thing to consider here is when to return home.

Typically, professional researchers who complete their PhD will continue to do postdoctoral research to gain experience. This is a very important stage to help them develop their research capacity, project management skills and build an international collaboration network.

I also thought that I would follow that path, continue as a postdoc for a few years before returning.

However, in 2018, I had the opportunity to meet some Vietnamese colleagues working in the country. They told me that Phenikaa University wanted to invite young scientists to work. Learning about the school's development orientation, I found many points that were suitable for me.

At that point, I started thinking seriously: If not now, then when?

Although science has no borders, if our efforts are put in the right place, they will bring much greater value. Vietnam will need us more than in places that are too developed like France.

Is there anything that makes you hesitate when deciding to return home when everything is not really ripe yet?

- Of course. When I decided to return home, I had to consider a lot.

What worries me most is feasibility. In Vietnam, scientific research, especially in the field of advanced materials, still does not have as many favorable conditions as abroad. I used to ask myself: "Am I being too hasty? Should I stay a few more years to accumulate experience before returning?"

In addition, funding for scientific research is also a big challenge. Abroad, research funds are abundant, facilities are modern, and there is a professional support team. But in Vietnam, I will have to build everything from scratch.

However, I also see opportunity in the challenge. If I build a lab from scratch, I will understand every detail of it. I will be able to take full control of my research in the future.

I also consulted some professors in France, and they fully supported my decision. They said that returning to my country did not mean that I was giving up science, but that I was opening a new direction where I could contribute more.

I received my PhD in October 2018 and returned to Vietnam in June 2019.

How did you "start over" when you returned home?

- The first time when I returned to Vietnam was a very difficult but also inspiring period.

It was also a coincidence that my new colleague, Dr. Bui Van Hao, after a period of research and postdoc in the Netherlands, had just returned to Vietnam and was also researching this atomic layer deposition (ALD) technology. At that time, in Vietnam, there were only two of us who were doing in-depth research on ALD.

On November 19, 2019, the two brothers decided to form a research group on ALD technology. But at that time, we had nothing in hand - no lab, no equipment, no personnel.

The first thing to do was to ask for funding to build a laboratory. We presented our proposal to the board of directors of Phenikaa University and were granted 2.4 billion VND. This is a relatively large amount in Vietnam, but in reality, building a standard laboratory in this direction can cost millions of USD.

Initially, we contacted companies that sell commercial machines. However, the minimum quote was $200,000 (about 5 billion VND) for a system, double the budget we had.

Furthermore, these systems often have only a few fixed features, making it difficult to intervene if design changes are needed to test new features.

How can research be made to be so constrained?

Besides, if we buy a commercial system, we will be completely dependent on the supplier. If even a small component breaks, I don't know how to fix it because I'm not a designer.

And this difficulty is also an opportunity for the first "made in Vietnam" SALD system?

- Yes, we gave up the idea of buying a commercial system and decided to design and make it ourselves.

We tried to convince the school board to invest. However, the teachers were very hesitant because they did not know what he was building. I understood this hesitation. From the school board's perspective, deciding to spend billions on an unclear system with unknown results was very risky.

Perhaps our determination and hope in the younger generation convinced the teachers and fortunately the funding proposal was approved, but this was only the first challenge.

The next difficulty is finding people to do it. I can grasp the technology, understand how to design, with what standards, but I really need a mechanical and electronic unit to realize these ideas.

I contacted many automation companies but all refused. They usually assemble available modules, but have no experience in building a completely new system from scratch, with many standards of mechanical precision at high temperatures, chemical safety, control stability, air tightness, etc.

By chance, I was connected with Mr. Diep, the owner of a manufacturing company in Dan Phuong.

Mr. Diep is an engineer graduated from Hanoi University of Science and Technology, I often jokingly call him an anonymous expert, not too famous but very good.

I called him and made an appointment to meet him on a Sunday afternoon. We met, made a pot of tea. I told him about my return from France to Vietnam, the difficulties I was facing, and my desire to design a completely new system.

With automation and micrometer-level precision, just a little extra heating is difficult, but my system consists of 5 elements from many fields combined…

Mr. Diep is very interested in difficult topics.

"I don't understand what you're trying to do, but I'll go with you," he told me bluntly.

For 2 years, my research team and Mr. Diep's company worked together to perfect the SALD system "screw by screw".

We ordered every detail, sat down and discussed what the standards were, for example how to choose the steel, what material the gaskets should be made of, how to resist chemical corrosion, how the air nozzle should be simulated and designed.

Have to wait for many months for the goods to arrive. Then build the mechanical connections, test run. Construction starts in 2021 and will be completed in early 2022.

How did you feel the moment you pressed the button and saw your "brainchild" working smoothly?

- I remember very clearly that it was February 2022. It was almost midnight, but I couldn't wait until tomorrow morning. I was so excited, so looking forward to this moment.

I was alone in the lab, did a final check, and then pressed the system start button.

Throughout the time of creating the system, I was under a lot of pressure. This was not just an experiment, but a real test. I had to prove to the management, colleagues and people who had put their trust in me that the research team could do it.

As the system began to operate, each process performed exactly as designed, I held my breath. When I saw the first layer of material being created, each atomic layer being precisely scanned, I knew I had succeeded.

I immediately recorded a video, alone in the room, saying loudly, "It's out, teachers! The nano-thin film material made by ALD at atmospheric pressure has been produced," and immediately sent it to my colleagues to report the good news.

How did the successful fabrication of the first atmospheric pressure atomic layer deposition (SALD) system in water create a turning point?

- This is a system that allows the fabrication of semiconductor metal oxide nano-thin films with thickness control down to the atomic monolayer level.

This system not only works stably, but is also much improved compared to the system I used to work in France. In France, I operated the system for 4 years, working with it every day. I clearly understood the limitations, and when I returned to Vietnam, I optimized the design, received many suggestions and advice from colleagues and Mr. Diep's company to overcome all those shortcomings.

Now, students, trainees, and researchers can operate the system themselves. This is what I have long wished for. If they just bought a commercial system, students would just know how to push buttons, but now, they can actually do science, and have the right to make mistakes…

If something goes wrong, we can fix it in a relatively short time (maybe a day to a week), because we know the design and can really feel and assess where it's broken.

In the next phase, we are working with partners to try to bring the technology into practical applications as soon as possible. Hopefully in 5 years, our conversation will be about how this thin film technology is coming into practice.

Some of the areas I see the most potential for right now are UV-resistant coatings in some polymer-based materials. Because polymeric materials can break down under UV exposure. You can imagine it like baskets left in the sun become brittle and easily broken.

We will apply a very thin nano layer that does not change the product's characteristics and can resist that.

The second segment is water filter membranes. Currently, RO membranes are mainly imported. We can completely use this technology to manufacture RO membranes, even process and coat them with anti-virus and anti-bacterial materials.

Or like Vietnam's orientation is to build a semiconductor chip factory, nanomaterial technology is a part of that.

Having worked and researched in Europe for a long time, what role do you think mastering high technology plays for a country?

- Research and development accounts for a very high proportion in today's high-tech products. For example, with smartphones, research and development researchers account for 60-70% of total profits on each product.

Developed countries now hold core technology, pushing production lines through developing countries, which only provide labor and suffer from some environmental problems.

The most important thing in the development of science and technology is to master the core technology, which here is the aspect of manufacturing technology. In the field of materials technology, mastering new manufacturing technology can hope for breakthroughs and application development.

Mastering core technology will help Vietnam solve the problem of exporting raw materials and importing refined products and ensure self-reliance, especially in the context of a volatile world.

If we still depend on technology, we will always be behind. Only in areas where we can be self-sufficient can we hope to develop breakthroughs and be pioneers.

What advice do you have for young people about pursuing scientific research?

- As a researcher and also a lecturer in charge of training at the faculty, I really hope that high-tech scientific research fields, especially basic science, will have more high-quality human resources.

In the process of modernizing the country, human resources are the most important. The policies have created the premise, but in the end, to operate and realize the potential, the human factor is still the factor. The next generation must be the generation that masters the country's science and technology, and we cannot rely too much on hiring foreign experts.

Young people who are good at natural sciences should boldly embark on the path of science and technology.

The treatment in Vietnam for scientists is much better than before. In some domestic research and training institutions, the treatment and spending levels for professional scientists are not inferior to those abroad.

In particular, with the boost from Resolution 57, Vietnam is entering a period of very strong investment in science and technology. I have great faith that there will be a generation of scientific breakthroughs in the near future.

Thanks for the chat!

Comment (0)