2023 could have been a year of peace and reconciliation in the Middle East. Over the past year, the world has seen Iran and Saudi Arabia – two regional powers and longtime rivals – restore relations and reopen embassies; seen Saudi Arabia and Israel move closer to normalizing relations; seen the Arab League accept Syria back into the fold; and saw the warring parties in Yemen commit to taking steps toward a ceasefire.

However, the situation changed on October 7 when Hamas, a Palestinian political -military organization, suddenly attacked southern Israel by land, sea and air, killing about 1,140 people (including soldiers). Israel immediately declared war, determined to wipe out Hamas through an unprecedented siege and bombardment campaign in the Gaza Strip, which was under Hamas' control. Israel's retaliatory attacks have killed more than 20,400 people in Gaza, as of December 25.

Ruins in Khan Younis, southern Gaza, in late November

The Middle East is being drawn back into a spiral of violence just as the prospect of lasting peace is beginning to emerge in a region that is deeply sensitive politically, religiously and ethnically. And with the nearly two-year-old war in Ukraine, the fighting in the Middle East has deepened the sense that peace, already fragile, is even more fragile.

While peace talks between Russia and Ukraine have long stalled, the Israeli-Palestinian peace process is now buried under bombs and bullets in the Gaza Strip. The “two-state” solution – the mainstay of plans to resolve the decades-long conflict between Israelis and Palestinians – is more difficult than ever.

Can a new peace process arise from the ashes of the current plight?

What future for the "two-state" solution?

The idea of a "two-state" - an independent Palestinian state, existing alongside an Israeli state - has been around for decades, according to The Economist . In 1947, the United Nations proposed a plan to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state, with the city of Jerusalem under international control. However, the Arabs rejected the plan and Israel declared independence in 1948, leading to the First Arab-Israeli War.

Before and after the creation of the State of Israel, some 750,000 Palestinians were driven from their homeland, which was then under the control of the fledgling Jewish state. In the 1967 Six-Day War, or the Third Arab-Israeli War, Israel captured the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan. Israel also captured the Gaza Strip from Egypt in that war but withdrew from the territory in 2005.

After decades of conflict, the Palestinians still did not accept the "two-state" solution until 1987 when the "intifada" broke out. Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) leader Yasser Arafat began to change his approach, acknowledging the existence of Israel and supporting the coexistence option, according to Le Monde .

Israelis and Palestinians began negotiations at a peace conference in Madrid in 1991. With the Oslo Accords of 1993, a “two-state” solution seemed within reach for the first time since 1948. The achievement also earned the then Israeli and Palestinian leaders the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994.

However, the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin by a right-wing extremist in 1995 stalled the peace process. Hopes were raised again at the Camp David conference in the US in 2000, but the effort ultimately failed. The Israeli-Palestinian peace process stalled in 2014 and there have been no serious negotiations since.

(From left) Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, US President Bill Clinton and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat at Camp David (USA) in 2000

SCREEN CAPTURE THE NEW YORK TIMES

The Hamas-Israel conflict has been less than three months old, but it has already led to the most serious bloodshed in Gaza since 1948 and appears to have dealt another blow to hopes of a “two-state” solution. But even without Hamas’s October 7 attack, the possibility of “two states” becoming a reality would have been slim.

According to a Pew Research Center poll in the spring of 2023, only slightly more than 30% of Israelis believe that it is possible to live peacefully with an independent Palestinian state. Ten years ago, one in two Israelis said they believed in a “two-state” solution. After the events of October 7, that number may be even lower.

The situation is similar in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem, where Gallup polls conducted before the Hamas attacks found that only about 25% of Palestinians there support a “two-state” solution. In 2012, 6 in 10 Palestinians supported the option.

A glimmer of hope

However, many parties still believe this is the only path to peace between Israel and Palestine, including the US. "When this crisis is over, there has to be a vision of what happens next, and in our view, that has to be a two-state solution," US President Joe Biden said about the Hamas-Israel conflict during a White House press conference in October.

US President Joe Biden

At a conference in Bahrain in November, Arab officials delivered a similar message. "We need to return to a two-state solution, an Israeli state and a Palestinian state living side by side," Anwar Gargash, an adviser to the president of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), told the conference.

Such an effort would have to overcome a number of obstacles, according to The New York Times , not least the dramatic expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, which Palestinians say has contributed to the destruction of their hopes of establishing a state on that land. The rise of ultra-nationalism in Israel further complicates the task: It opposes Palestinian statehood, seeks to annex the West Bank, and understands that the removal of Jewish settlements there is a “political powder keg.”

Palestinians protest against Jewish settlements in Nablus, West Bank, in September 2023

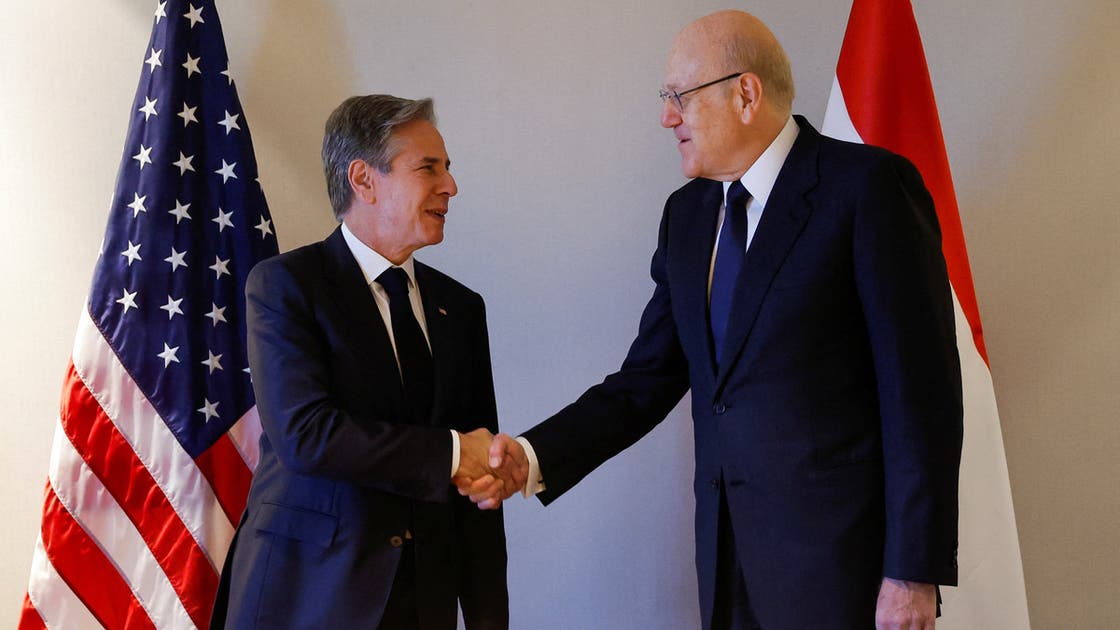

One of the leading advocates of a “two-state” solution is Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati, who launched a peace plan after the Hamas-Israel conflict erupted. In an interview with The Economist in October, he said the plan involved three steps.

The first is a temporary five-day humanitarian ceasefire, in which Hamas would release some hostages and Israel would cease fire, allowing humanitarian aid into Gaza. If the temporary ceasefire holds, the plan would move to the second phase: negotiations for a full ceasefire. With the help of intermediaries, Israel and Hamas could also negotiate a prisoner-for-hostage exchange.

Western and regional leaders will then begin work on the third phase: an international peace conference aimed at a “two-state” solution for Israel and Palestine. “We will consider the rights of Israel and the rights of Palestinians. It is time to bring peace to the whole region,” Mr Mikati said in the interview.

Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati (right) met with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in Jordan in November 2023

Hope for peace remains, according to Tony Klug, a former adviser to the Palestine Strategy Group (PSG) and the Israel Strategy Forum (ISF). Writing for The Guardian in November, he pointed out that every Israeli-Palestinian peace process since 1967 has been spurred by an unforeseen “seismic event.” This Hamas-Israel war could be one such event.

Specifically, Klug said, the 1973 Yom Kippur War, or the Fourth Arab-Israeli War, led to a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel in 1979. The 1987 events spurred diplomatic initiatives that culminated in the 1993 Oslo Accords. The 2000 events spurred the 2002 Arab peace initiative. While it is too early to say with confidence, it is possible that the current wave of outrage will follow a similar pattern, Klug said.

Israeli officials say they are focused on the war against Hamas, which could last for months, and any discussion of a peace process must wait until Gaza is quiet. But in think tanks and in the recesses of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, talk of a “post-war” political process has already begun, according to The New York Times .

EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell

The European Union (EU) has called for an international peace conference to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, an idea supported by Spain, which hosted a landmark Middle East peace conference in 1991. The Arab world could also initiate peace talks, although Egypt’s recent efforts have yielded little results.

"Peace will not come by itself; it must be built. The two-state solution remains the only viable solution we know. And if we have only one solution, we must devote all our political energy to achieving it," The Guardian quoted EU Foreign Policy Chief Josep Borrell as saying.

Hardships in Ukraine

Ukrainian officials said in November that a global “peace conference” on Ukraine could take place in February 2024, amid Western concerns that the Gaza war was making it harder to win diplomatic support for Kyiv’s peace plan.

Kyiv had wanted the summit to take place in late 2023 to build a coalition behind Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky's 10-point "formula" to end the war with Russia. Kyiv has hosted a series of talks involving dozens of countries without Russia in an effort to build up to the summit.

Western diplomats say Ukraine’s efforts to win support have lost momentum due to rising tensions in the Middle East. The Hamas-Israel conflict has caused new rifts between the United States and other Western countries and some of the Arab powers and leading developing nations that Ukraine had hoped to win over, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Source link

![[Photo] Solemn opening of the 1st Government Party Congress](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/13/1760337945186_ndo_br_img-0787-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam attends the opening of the 1st Government Party Congress](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/13/1760321055249_ndo_br_cover-9284-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)