After 8 years of living in Iceland, Ms. Nguyen Phuc is no longer as scared as the first time she felt the tremors when the volcano erupted.

On January 14, two volcanic eruptions occurred on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland, sending lava into the southwestern town of Grindavik, destroying several homes. This was the second eruption on the peninsula in less than a month, and the fifth since 2021, after 800 years of dormancy.

Icelandic President Gudni Johannesson called on people to keep hope and overcome difficulties, as lava poured into Grindavik, where people "have built their lives, doing fishing and other jobs, creating a harmonious community".

Lava from a volcano flows into the town of Grindavik on the Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland on January 14. Video: X/Entroverse

Nguyen Phuc, a Vietnamese living in the town of Njardvik, about 15 km from the eruption, said this was the first time lava had entered a residential area in Iceland, causing major infrastructure damage in decades.

"Everyone is looking towards Grindavik, everyone seems to be sad and regretful for those who lost their long-time homes because of the volcanic lava," Ms. Phuc told VnExpress .

The Vietnamese community in Iceland responded strongly when the government and charitable organizations called for donations to support people affected in Grindavik through the Red Cross.

"Icelanders know all too well the pain of losing homes to lava in history, so whenever a volcano erupts, neighboring areas immediately lend a helping hand, even on offshore islands," said Eric Pham, 40, a Vietnamese tour guide in Iceland.

Location of the town of Grindavik. Graphics: IMO

Situated between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates, two of the largest tectonic plates on the planet moving in opposite directions, Iceland is a hotbed of seismic and volcanic activity. The country experiences up to 26,000 earthquakes a year.

When she first arrived in Iceland in 2015, Ms. Phuc was very frightened by the first earthquake. But 8 years later, she considers earthquakes a daily occurrence, because this phenomenon happens so often, while Iceland has developed an advanced disaster warning system, helping people take safety measures.

Jon Orva, a risk manager at Iceland’s disaster insurance agency, said homes in the country must be built to strict standards for design, materials and able to withstand earthquakes of less than magnitude 6. Information about the construction is made public locally, making management transparent.

Officials and scientists also closely monitor seismic and volcanic activity. Iceland has the most active volcanoes in Europe, with a total of 33 monitored sites. This is also the reason why Iceland's geology industry is so developed.

"We are warned early about even the smallest seismic activity. Volcano and earthquake prevention are also taught in the education program," said Nguyen Thi Thai Ha, a math teacher in the capital Reykjavik, pointing out that the sparse population density, sense of compliance and spirit of community support also play a big role.

In fact, the residents of Grindavik had been warned about seismic and volcanic activity in the area for months. When the volcano erupted, the entire population was evacuated during the night, so no casualties were recorded.

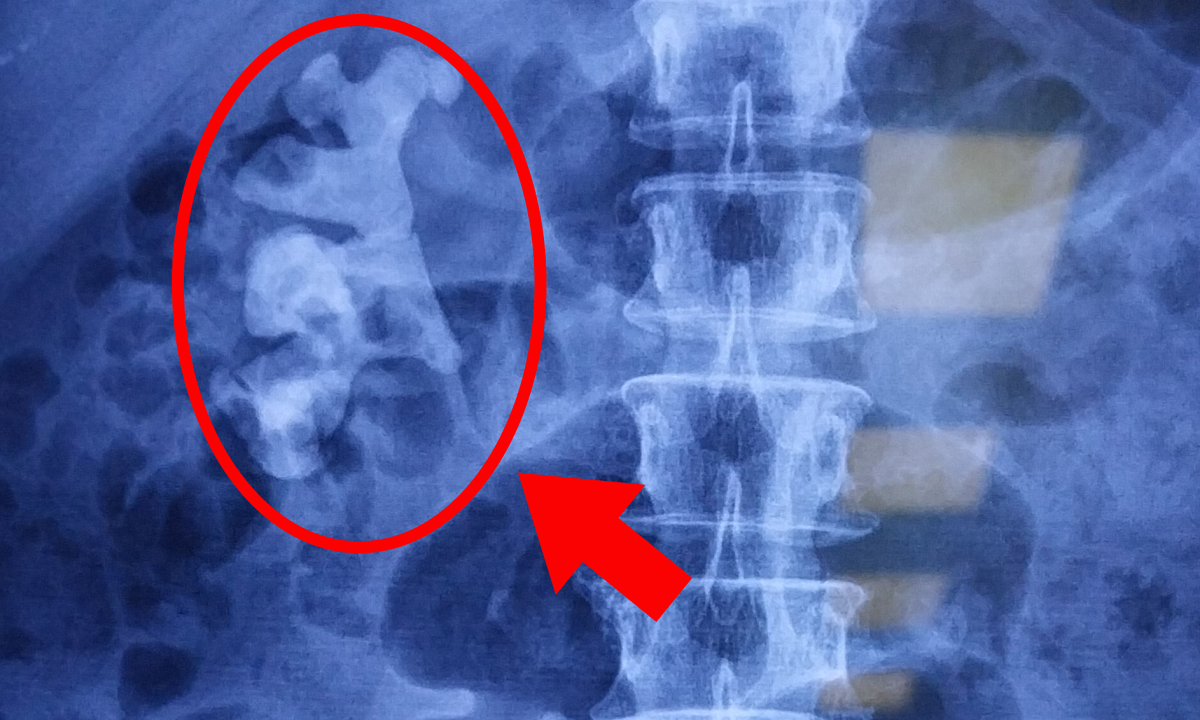

Authorities had previously built a wall of earth and rock outside Grindavik to block the lava flow. The wall proved effective during the first eruption, which occurred at 8 a.m. on January 14, when a fissure appeared in the ground outside the town. Lava flowed toward the town, but was blocked by the wall.

By that evening, a second fissure about 100 meters long had appeared at the edge of town, rendering the perimeter wall useless. Lava poured into Grindavik, engulfing several homes.

Icelandic authorities build a wall to stop lava from flowing into the town of Grindavik, January 14. Photo: AFP

The Vietnamese community in Iceland said that the local authorities' ability to manage and warn of natural disasters helped them feel secure in "living with the volcano" and their lives were not too disrupted during the most recent eruption.

"Luckily, this eruption did not produce ash, so flights were not affected," said tour guide Eric Pham. "In fact, tourists are happy to see the volcano from above when flying."

Trips to see lava flows have become a tradition for many Icelandic families. "Every time a volcano erupts, most Icelanders wait to see it," says local photographer Ragnar Sigurdsson.

Officials will monitor and measure toxic gases in the area of the eruption and notify residents when it is safe. They will also set up climbing ropes, set up parking lots, makeshift toilets, and have rescue teams stationed outside to make it easier for people to admire the volcano.

"Everything is very well planned and free, you only have to pay for parking," Eric Pham commented. During his 10 years living in Iceland, Eric Pham had 5 opportunities to watch volcanic eruptions, including one time by helicopter.

"It's like a mountain climbing or picnic, people bring hot dogs and pizza to grill, but still need to keep their distance because the lava is very hot," he said.

After many years of not daring to go because of fear, Ms. Ha and her friends went to see the volcano erupt for the first time in August 2022. When she arrived, she was surprised to see a long line of people crossing the dangerous terrain to admire the lava flow. "At that moment, I felt truly lucky to witness the boiling of a volcano with my own eyes for once in my life," said the 32-year-old teacher of Vietnamese origin.

Nguyen Thi Thai Ha takes a photo next to a lava flow in Iceland, August 2022. Photo provided by the character

Duc Trung

Source

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs the Government's special meeting on law-making in April](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/13/8b2071d47adc4c22ac3a9534d12ddc17)

![[Video] Using beauty to eliminate ugliness - An effective remedy against "dirty livestreams"](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/13/931f77476e68477eac7b0b6c704b51ae)

![[Photo] Closing of the 11th Conference of the 13th Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/12/114b57fe6e9b4814a5ddfacf6dfe5b7f)

Comment (0)