The Spring Festival excursion was supposed to take place six weeks ago. A series of troublesome situations occurred, bad weather, illness of the empress dowagers and concubines, difficulties caused by the regents, I don't know what else, all caused the trip to be delayed.

We had made that journey eight days earlier, on a glorious afternoon. The day before, along the routes the procession had taken, flags and banners of all colours had fluttered in the wind, and the people of the city and the neighbouring villages had set up small altars laden with fruit, covered with golden parasols, incense burners and lamps arranged in a row.

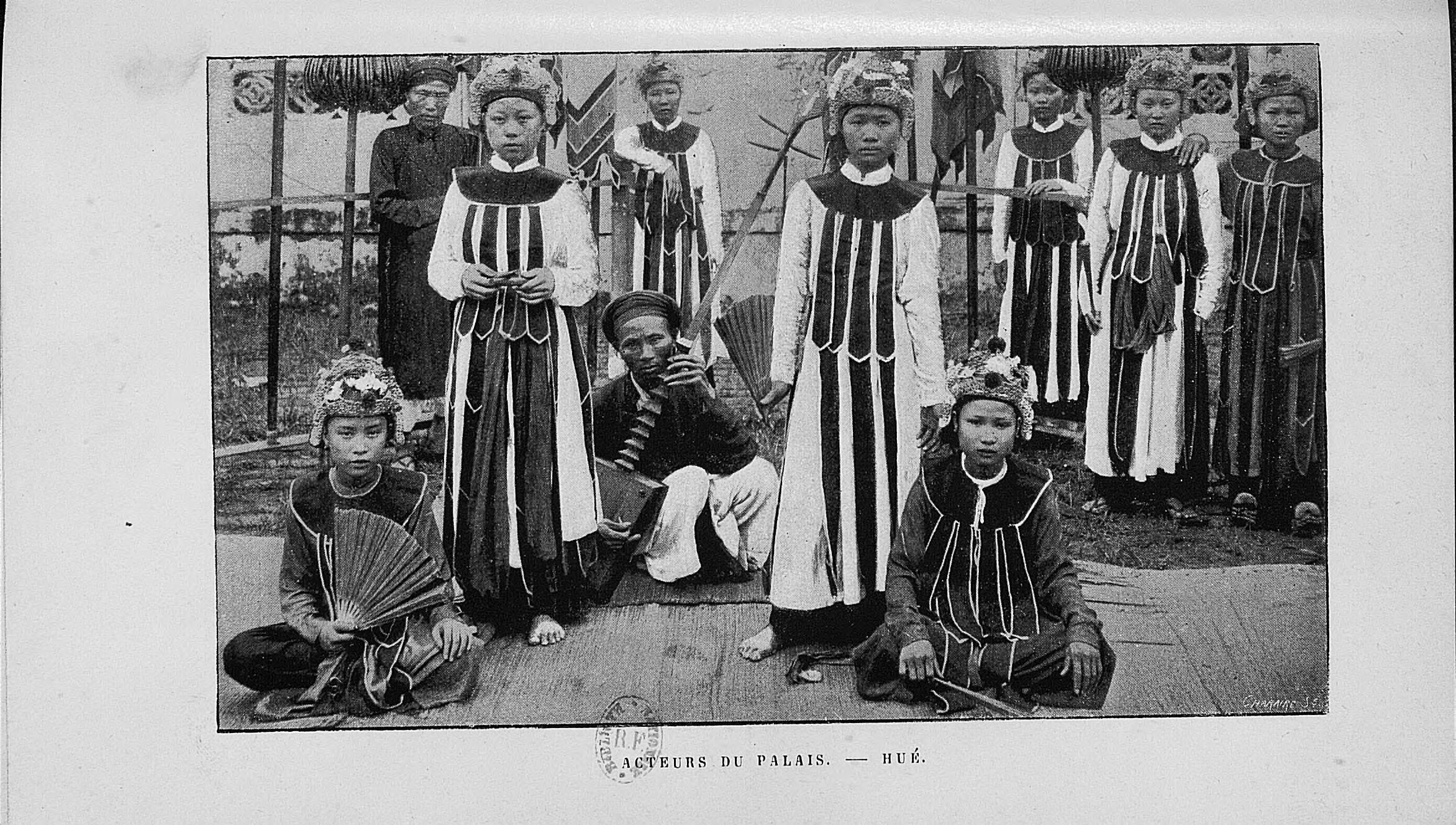

Hue Royal Court Artists

The festival began with a visit to the Imperial Envoy's Palace. The King, escorted by his guards in red and painted hats, walked towards the river, where the royal barge was waiting. There, barefooted men, lined up as neatly as possible, some brandishing spears, others carrying rifles. The whole scene was solemn. The sunlight made old clothes look new, and people admired the mandarins in their beautiful silk ceremonial robes, flanked by umbrella-bearers, pipe-bearers and betel-nut trays.

A long boat, manned by about 40 oarsmen, towed the royal boat, and at the bow the commander, holding a megaphone, gave orders, pacing back and forth, gesticulating, and appearing very moved by his responsibility as if he were commanding a patrol boat in danger. To make things even more certain, a devoted servant, and more than that, a good swimmer, swam alongside the boat to save the royal family in case of a sinking.

The crossing took ten minutes. From the boat dock to the Apostolic Nunciature, the marines stood as a guard of honor. The distance was at most 100 meters. King Thanh Thai sat in a palanquin the entire way, his appearance majestic, his eyes fixed, his hands clasped, like a Buddha statue. At the threshold, the king slowly and solemnly walked up each step, then crossed the large lobby and the first living room.

A light meal had been prepared. At the king's table, there were only the Resident, the Commander of the Army, and the highest-ranking person in the court after the king - Tuy Ly Vuong, son of King Minh Mang. At his advanced age, over 80, he still bowed when he saw the king. It was strange to see this old man kneeling before a young king - who received the homage calmly, his face haughty, in a long golden cloak studded with gems, shining like a reliquary.

However, once seated at the table and the champagne poured, King Thanh Thai showed his true nature. The idol was replaced by a handsome boy, looking from object to object with curiosity and hopping like a daring sparrow. Through the large window, the young king stopped to observe the group of guests gathered in the next room, around the lavishly prepared banquet: there were about 30 officers and civil officials, but no women. Women were not allowed to attend such gatherings.

The conversation was limited to small talk. Moreover, the king was very sparing; a few words about the former Governor-General, a greeting to the new Governor-General, a few questions about a detail related to the interior, about a painting, about a curtain, that was all. However, it was clear that the king was in a good mood and tried to prolong the visit. The two younger brothers of King Thanh Thai, two children between 8 and 10 years old, were also having fun. Dressed in green, they stood behind the king's chair, eating cakes, almond candies and talking.

After an hour, the king withdrew, crossed the river again, and continued his tour of the city. Until evening, the long procession marched on both sides of the Dong Ba River. The people had to hide in their houses to show respect: watching the king pass by and looking at him was considered blasphemy. Only a few old men knelt before the small altar with incense burners smoking. Those who had endured the hardships of life for a long time were given some privileges.

As I contemplated this religious spectacle, as I saw the white heads bowing before the living idol whose journey brought good fortune to the city, made flowers bloom, fruits ripen, made the sick healthy, and gave hope to the poor, I understood how deeply rooted the adherence to traditional customs and rituals were in the soul of this nation, and those who thought they could abolish all of them without the need of time were either reckless or naive.

It was only after sunset that the procession slowly returned to the city. The last of the escort had long since disappeared, and we could still guess the path the procession had taken by the dust that rose under their footsteps, by the golden powder that hung in the still air. (to be continued)

(Nguyen Quang Dieu quoted from the book Around Asia: Cochinchina, Central Vietnam, and North Vietnam, translated by Hoang Thi Hang and Bui Thi He, AlphaBooks - National Archives Center I and Dan Tri Publishing House published in July 2024)

Source: https://thanhnien.vn/du-ky-viet-nam-le-nghinh-xuan-185241211224355723.htm

![[Photo] Visiting Cu Chi Tunnels - a heroic underground feat](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/8/06cb489403514b878768dd7262daba0b)

Comment (0)