As negative electricity prices from rooftop solar power surge, California's state government is scrambling to figure out how to deal with the excess electricity.

Homes covered in solar panels in California. Photo: Adobe

In sunny California, solar panels are everywhere. They line the arid desert landscape of the Central Valley and dot the rooftops of downtown Los Angeles. California has nearly 47 gigawatts of installed solar capacity, enough to power 13.9 million homes and more than a quarter of the state’s electricity, according to the latest count. But now the state and the grid operator are grappling with a strange situation. Too much solar on sunny days when demand is not so high has led to negative electricity prices, according to the Washington Post .

To address this, California has stopped encouraging rooftop solar installations and slowed installations. But the shrinking economic benefits could slow the growth of solar in a state that is trying to transition to renewable energy. As other states build more solar plants, they may soon face the same problem.

“It’s an insurmountable challenge,” said Michelle Davis, global solar director at energy research and advisory firm Wood Mackenzie Power and Renewables. “But it’s a challenge that many grid operators have never addressed.”

Solar power has many great benefits: it costs almost nothing to operate once built, it creates no air pollution, and it produces energy without burning fossil fuels. But its main disadvantage is that the Sun doesn't shine all the time.

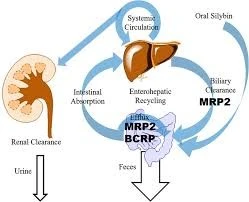

More than 15 years ago, researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory modeled the future of widespread solar power and noticed something strange. When there was a lot of solar on the grid, the gap between demand for electricity and renewables became U-shaped. The morning surge in demand would be replaced by near-zero demand at noon, when solar could produce all the electricity people needed. Then, when the sun went down, demand would spike again.

California’s grid operator, CAISO, calls this effect the “duck curve.” It’s most noticeable in the spring months, when solar panels get plenty of sunshine but little demand for heating and cooling. In recent years in California, the duck curve has become a giant canyon, with solar power sitting idle. In 2022, the state wasted 2.4 million megawatt hours of electricity, 95% of which was solar. Last year, the state experienced that much waste in just the first eight months of the year.

Clyde Loutan, director of renewable energy integration at CAISO, said California has long been preparing for more solar on the grid, but it underestimated the pace of home solar development.

Cutting back on solar power isn’t technically difficult, says Paul Denholm, a research fellow at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. But cutting back on your own generation raises your electricity prices and reduces the benefits of rooftop solar. Since the 1990s, California has paid rooftop solar owners to feed energy into the grid. That means they get $0.20 to $0.30 for every kilowatt-hour they produce.

But a year ago, the state changed that system and now compensates new solar owners only for the value of their electricity to the grid. In the spring, when the duck curve is deepest, the amount can drop to near zero. Customers can get more money if they install panels and feed power into the grid in the morning or early evening. The change has been met with fierce opposition from Californians and rooftop solar companies. The utility company Wood Mackenzie predicts that California solar installations will fall by about 40% by 2024.

Other states that have been slower to adopt solar than California are starting to see similar results. Nevada, which gets 23% of its electricity from solar, has also seen its duck curve deepen. Hawaii, where thousands of homes have rooftop solar, has seen its payments to those households drop.

California’s grid operators hope their experience will provide lessons for other states. CAISO is selling surplus power to several neighboring states. California also plans to install batteries and other solar storage systems to use at night. Transmission lines could also help distribute power more evenly. Some outages have come from areas that don’t have enough lines to handle a sudden surge in solar power.

An Khang (According to Washington Post )

Source link

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs meeting on US imposition of reciprocal tariffs on Vietnamese goods](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/5/9b45183755bb47828aa474c1f0e4f741)

![[Photo] Hanoi flies flags at half-mast in memory of comrade Khamtay Siphandone](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/5/b73c55d9c0ac4892b251453906ec48eb)

Comment (0)