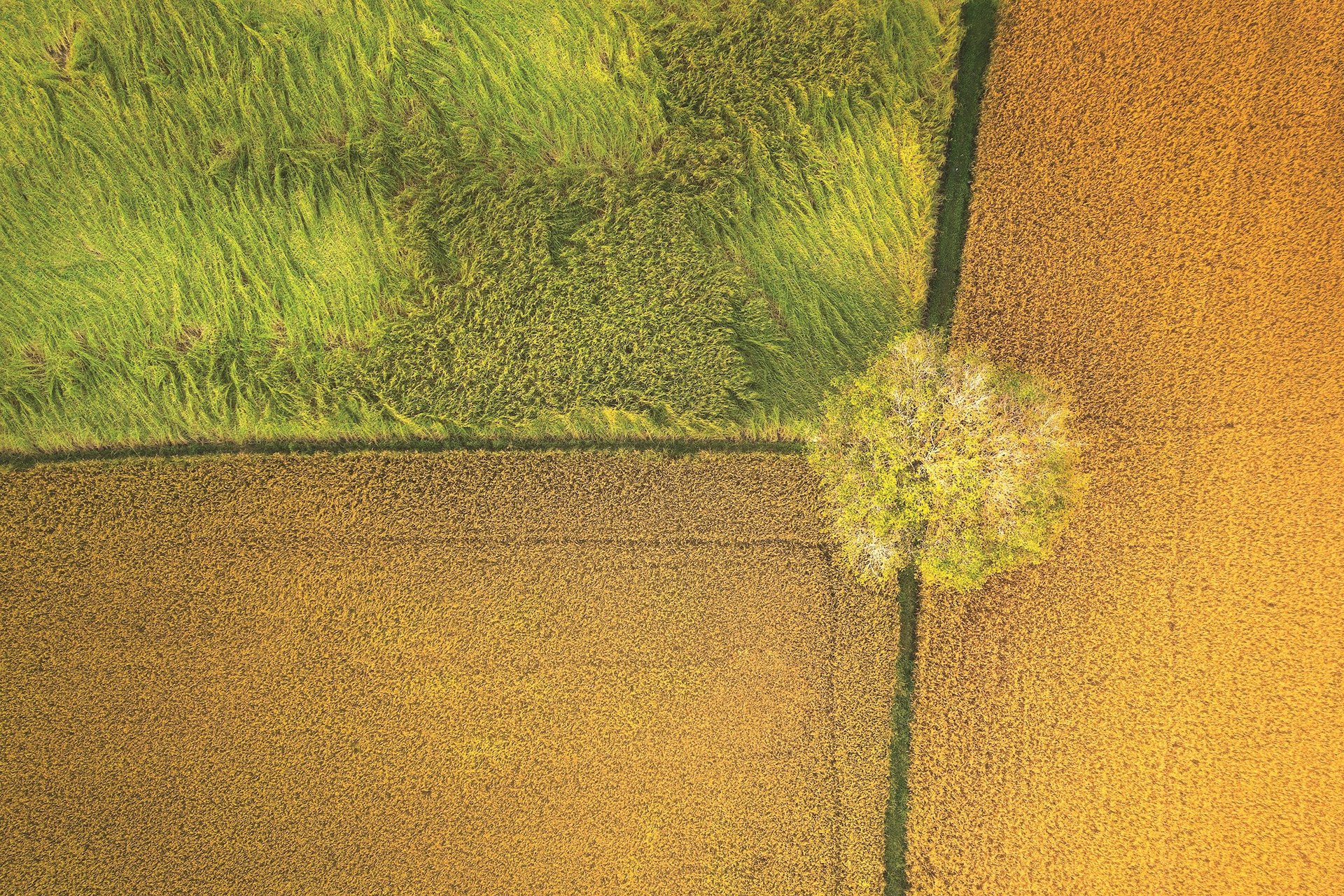

Isn’t it interesting to see your country through the eyes of an eagle? You nod, “Plus, aerial photography makes you see how small the things on earth are, like children’s toys, and how we (you trace your finger along the crowded road in the large photo hanging in the middle of the room) are like ants. Seeing how small we are has its own charm.”

You say this for a reason.

Invite each other to sit at a coffee shop, you tell me about a trip to your hometown at the beginning of the year. The moment you saw the house you used to live in through the plane window, more than ten minutes before the plane landed, you thought about where fate was.

Or maybe it was your father's spirit right next to you, he was the one who urged you to sit by the window, he was the one who cleared the clouds, so you could see and locate the house right away, thanks to the Thuy Van water tower right next to it, thanks to the land bank jutting out right at the river junction. You could recognize it at a glance, even though the roof had changed its tile color, a few outbuildings had been built to the back, and in the garden the trees had grown taller.

That is your scientific brain that imagines based on proportion, but everything down there is like a modest toy, even the majestic water tower that when you were a child, when you went out a bit far, you used as a landmark to return home, now only a span longer. At that moment, you fix your eyes on the house, the garden, taking in its pitiful smallness, thinking about yourself, about the battle you are about to enter, about the surprise attacks to ensure victory.

Just a few minutes before, when the flight crew announced that the plane would land in ten minutes, you were still opening the envelope containing the documents to review, estimating the time of the appointment with the lawyer, muttering convincing arguments in your head, imagining what the other side would say, how you would rebut. Leaving the visit to your father's grave for last, before leaving with the inheritance in hand. After two and a half days at the place where you spent your childhood, you and your half-siblings probably couldn't sit down to eat a meal together, because of your hostile thoughts about each other. They thought it was absurd that you hadn't been close to your father for twenty-seven years, and now you showed up to demand a share of the inheritance, like snatching something from his hands.

You remember your mother's efforts when she was alive, she single-handedly built the house, from a small plot of land with only enough space left for a ten-hour bush, she saved up to buy more, and expanded it into a garden. The family could not just enjoy it peacefully. No one would give in, once their views did not meet, they had to meet in court.

But the moment you look down from above at that pile of assets, its smallness makes you think that even if you cut it with just one stroke of the knife, it would fall into pieces, nothing more. Memories suddenly bring you back to the train your father took you to live with your grandmother, before he remarried a librarian, who later gave birth to three more daughters.

The friends bought soft seats, sparing each word, because of the many mixed emotions in their hearts before the separation, because they knew that after this train ride, their feelings would never be the same again. Both of them tried to shrink as much as possible, sinking into their seats, but could not avoid the chatter around them.

A family of seven was quite noisy in the same compartment, as if they were moving house, their belongings were spilling out of the sacks, the plastic bags were bulging, the little boy was wondering if the mother and daughter hens in the cargo hold were okay, the old woman was worried about the armchair that had come loose, after this it would probably break a leg, a girl was sobbing, not knowing where her doll was. “Did you remember to take the lamp for the altar?”, questions like that kept popping up on the sunlit train tracks.

Then, still in a loud voice, they talked about the new house, how the rooms would be divided, who slept with whom, where the altar should be placed, whether the kitchen should be in the east or south to suit their age. They regretted that the old house would probably be demolished soon, before people built the road leading to the new bridge, "when it was built, I cleaned every brick, now thinking back I don't feel sorry for it".

Around noon, the train passed a cemetery spread out on white sand. The oldest man in the family looked out and said, “One day I will be just as small as that, and so will you all. Just look.” The passengers in the cabin had the opportunity to look at the same place again, only this time they did not marvel or exclaim like when they passed by the flocks of sheep, the fields of dragon fruit laden with fruit, and the headless mountain. Before the rows and rows of graves, people were silent.

“And twenty years later, I remember that detail the most, when I looked at the houses scattered on the ground,” you said, moving your hand on the table to make way for the puddle of water at the bottom of your coffee cup, “suddenly an association jumped into my head, which I must say was quite inappropriate, that the houses down there were the same size and material as the graves I saw from the train when I was thirteen.”

A phone call interrupted the story, that day, I hadn't even heard the ending before you had to leave. While you were waiting for the car to pick you up, I said I was curious about the ending, what about the inheritance, how the half-siblings were fighting, who won and who lost in that battle. You laughed, then just imagine it was a happy ending, but that happiness doesn't lie in who won how much.

Source

Comment (0)