Instead of tightening fiscal policy when inflation is high and unemployment is low, rich countries are taking "unbelievably bold" steps to do the opposite - increasing spending and borrowing, according to the Economist.

Government budgets in rich countries are increasingly strained. Although the US avoided a debt default, it ran a budget deficit of $2.1 trillion in the first five months of the year, equivalent to 8.1% of GDP.

In the European Union, politicians are finding that rising interest rates mean that the $800 billion recovery spending package will drain the public purse, much of it borrowed.

The Japanese government recently dropped the timetable for an economic policy framework to balance its budget, which excludes current account payments, but the deficit remains at more than 6% of GDP. On June 13, the yield on two-year British government bonds rose above the level seen during the bond crisis triggered by the temporary budget in September last year.

US budget deficit. Source: The Economist

Rich countries' fiscal policies not only seem reckless but also inappropriate for today's economic circumstances, according to the Economist .

Given the circumstances, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) kept interest rates unchanged on June 14, waiting for further signals on the health of the economy. But with core inflation above 5%, few believe interest rates will remain unchanged.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is also poised to raise interest rates again, with the Bank of England (BoE) almost certain to follow suit on June 22. With nominal wages up 6.5%, Britain is the only country facing the threat of a spiral of rising wages.

High inflation, low unemployment and rising interest rates mean the world needs contractionary policy, meaning restraint in spending and borrowing. But rich countries are doing the opposite. The US deficit has only previously exceeded 6% in times of turmoil: during World War II, after the global financial crisis and most recently after the Covid-19 lockdown.

There is no such disaster that would require emergency spending. Even the European energy crisis has eased. So the main purpose of massive government borrowing is to stimulate the economy, pushing interest rates higher than they should be. Higher interest rates make financial instability more likely.

Government budgets are also affected. For example, for every one-percentage-point increase in interest rates, the cost of servicing the UK government’s debt increases by 0.5% of GDP over a year. One reason for the US’s difficulties is that the Fed has to pay more interest on the money it creates to buy back US government bonds in stimulus years. In short, monetary policy can only control inflation if fiscal policy is prudent. The risk of losing control increases as interest rates rise.

But politicians have done little to change that. Even after the “Fiscal Responsibility Act” raised the US debt ceiling and cut spending, the country’s net public debt is forecast to rise from 98% of GDP today to 115% by 2033.

The British government planned to tighten its belt last year but now plans to cut taxes. The eurozone looks solid enough overall but many member states are fragile. At current interest rates – and likely to rise – reducing Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio by one percentage point a year would require a pre-interest budget surplus of 2.4% of GDP.

Why do some rich countries continue to increase spending, even though they may be borrowing more? It may be due to politicians’ views on what is urgent or their familiarity with the deficit model.

In Italy, public debt as a share of GDP has cooled from its peak of 144.7% in December 2022 but remains significantly higher than the 103.9% level in December 2007, according to economic data organization CEIC Data. Debt is high but the country needs many items that need increased spending.

Pension and health care systems face pressures from an aging population. Carbon neutrality targets require public investment. Geopolitical risks increase the need for defense spending. Meeting these demands requires higher taxes or accepting more money printing and higher inflation.

In the United States earlier this month, after Congress authorized the 103rd increase in the debt ceiling since 1945, observers believe there will be a 104th and more. Adel Mahmoud, chairman of the Cairo Economic Research Forum (Egypt), said that the debt ceiling crisis will happen again because the US government has been spending beyond its revenue and relying on borrowing to finance its operations.

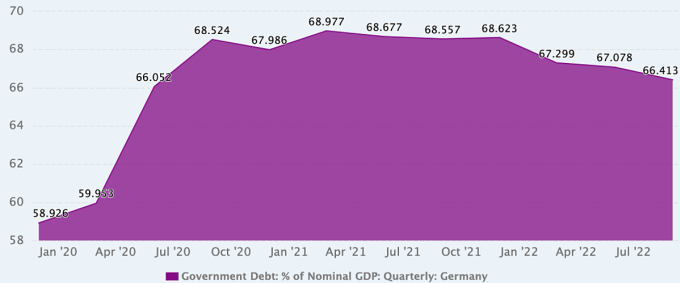

Even in Germany, a country famous for its fiscal discipline, with public debt at just 66.4% of GDP at the end of last year, views on fiscal policy are gradually changing and are becoming a subject of debate.

Evolution of Germany's public debt-to-GDP ratio. Source: CEIC Data

After facing successive crises due to the pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, Germany has moved away from its characteristically tight fiscal policy. In 2020, after eight years of balanced budgets (2012-2019), with total public debt falling from around 80% of GDP to just 60%, then-Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that the country was ready to spend heavily to offset the economic impact of Covid-19.

And as the impacts of climate change become clearer, some in German politics — notably the Green Party — argue that it should be treated as an urgent problem that requires investment on par with pandemics and wars.

Marcel Fratzscher, president of the German Institute for Economic Research, agrees. He says that increased spending should be considered when weighing the pros and cons of moving quickly and cheaply, or slowly and more challengingly. “If the German government were honest, it would recognise that we are in a state of almost permanent crisis, that we are facing major transformations ahead, and that this is not an option,” he says.

But some German economists see the past three years as a fiscal outlier, and want to reinstate the debt-inflating mechanism as soon as possible. They argue that the government has been able to spend freely during the pandemic because of its savings in previous years.

Niklas Potrafke, an economist at the Ifo Institute for Economic Research in Munich, Germany, said the government's response to the pandemic with expansionary fiscal policy was good. But the conflict in Ukraine has caused another crisis and further expansionary fiscal policy. "I am worried that the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have created a mentality of perpetually increasing budget spending. The government needs to consider consolidation strategies," he said.

Phien An ( according to Economist, FP, Xinhua )

Source link

![[Photo] Overcoming all difficulties, speeding up construction progress of Hoa Binh Hydropower Plant Expansion Project](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/12/bff04b551e98484c84d74c8faa3526e0)

Comment (0)