China’s estimated $200 billion food delivery industry, the world’s largest by revenue and order volume, doubled during three years of COVID-19 lockdowns and provided a steady income for the country’s seasonal workers. But not anymore.

Food delivery workers wait to take orders outside a restaurant in Beijing, China. (Photo: Getty Images)

China's economy is grappling with a range of difficulties, from a prolonged real estate crisis to weak consumer spending, which has also hit delivery drivers hard.

“They have to work long hours and are really squeezed,” said Jenny Chan, an associate professor of sociology at Hong Kong Polytechnic University. “They will continue to face pressure because delivery platforms have to keep costs low.”

The sluggish economy means people are spending less on meals, which has reduced the income of food delivery drivers, who rely largely on the number and value of orders, forcing them to work longer hours to maintain their income, Ms. Chan said.

Additionally, the dominance of two major food delivery platforms in mainland China allows the companies to dictate contract terms, leaving workers in the industry with few avenues to protest deteriorating working conditions.

Large labor force

About 12 million drivers make up China's vast food delivery network, which began to flourish with the launch of the Ele.me app in 2009, now owned by tech giant Alibaba.

Food delivery drivers have played a vital role in the COVID-19 era, when people were banned from leaving their homes under strict lockdown orders from the Chinese government. Now, food delivery has become an integral part of the country's culinary culture.

Food delivery people are everywhere, they rush through crowded streets or dark alleys to deliver food every day, even in heavy rain or storms.

Meituan food delivery workers deliver food amid a storm in China. (Photo: Xinhua)

China's food delivery market will reach $214 billion by 2023, 2.3 times more than in 2020, according to estimates from iiMedia Research, a consumer trends tracker. The industry is expected to reach $280 billion by 2030.

However, drivers in the industry today are under great pressure to meet the "must deliver quickly" requirement for each order, regardless of having to drive in the wrong direction, speed or run red lights, endangering both themselves and other road users.

But they still have no control over their earnings. One delivery man smashed his mobile phone on the sidewalk after receiving a negative review from a customer. He said the customer’s complaint against him was unfounded, but the company still deducted performance points, which reduced his income.

"Do they want to destroy my way of life?" , the man was indignant.

Income reduction

Last year, profits soared at two of the industry’s biggest players, Meituan and Ele.me. Meituan’s revenue hit $10 billion, up 26% from 2022.

Alibaba reported revenue of $8.3 billion, driven largely by Ele.me, in the fiscal year ended March 31, up 19% from the previous year.

However, the income of food delivery staff has decreased significantly.

According to a report by the China New Employment Research Center, food delivery workers earn an average of 6,803 yuan ($1,100) a month. That’s nearly 1,000 yuan ($150) less a month than they did five years ago, although many report driving longer hours.

Lu Sihang, 20, told CNN that he works 10-hour shifts, delivering 30 orders a day, earning about 200-300 yuan ($30-44) per shift. Lu has to work almost every day to earn an average of 6,803 yuan.

Gary Ng, an economist at French investment bank Natixis, points to China's "weak spending." As the Chinese economy slows, consumers spend less.

Mr. Gary said that although food is a basic need, the difficult economy means that consumers will spend less money on food delivery services, while restaurants will have to reduce prices to attract customers.

That reduces the income of delivery staff because their income is largely based on commission on order value.

In addition, the sluggish economy means fewer jobs, making competition fierce. China’s youth unemployment rate jumped to 18.8% in August, the highest since the government changed its statistical method last year to exclude graduates who continue their studies.

“If the labor supply is large, the bargaining power of workers will decrease, while the number of orders is limited,” Gary said.

Food delivery workers wait to take orders at a restaurant in Beijing, China. (Photo: Getty Images)

The Dominance of Platforms

Research by China Labour Bulletin, a Hong Kong-based NGO, said delivery apps initially spent heavily to offer higher wages to attract enough workers to serve their expanding markets.

“But as conditions changed, platform companies, once they took over the market, developed algorithms to control the labor process, leaving delivery people with few protections and losing a certain degree of freedom,” the report said.

Many restaurants don't charge a delivery fee. Some even offer deals that are cheaper than eating in or picking up.

Platforms invest heavily in the early stages to cut prices to eliminate competitors, but once they gain dominance, they begin to shift the cost burden to drivers by cutting bonuses and wages, says expert Jenny Chan.

Earlier this year, state-run online portal Workers.cn reported receiving a number of complaints from drivers in the industry.

A food delivery man said he was fined 86 yuan (over 300,000 VND) for not accepting a delivery order, even though he had informed the restaurant that he would not accept the order because they did not prepare the food on time, Workers.cn reported.

Expert Chan pointed out the issue of labor safety when food delivery workers earn income based on completed orders instead of monthly salary, which motivates them to brave dangerous road or weather conditions to deliver as many orders as possible.

According to the Global Times , in 2019, a driver died on the way to deliver food when a tree fell on him during a rainstorm in Beijing.

In early October, a video went viral on social media showing a food delivery man driving an electric scooter through a red light and crashing into a car at an intersection in Hunan Province, southern China.

Yang, a 35-year-old food delivery worker, acknowledged the downsides, saying the industry was “not as good as it used to be.” But he still felt the job suited him after working in a variety of jobs, from selling snacks to working in an office.

“This is a flexible job. If you want to make more money, you have to work more. You can also work less to rest when you need to,” Yang said.

Source: https://vtcnews.vn/gam-mau-u-toi-dang-sau-thi-truong-giao-do-an-lon-nhat-the-gioi-ar903527.html

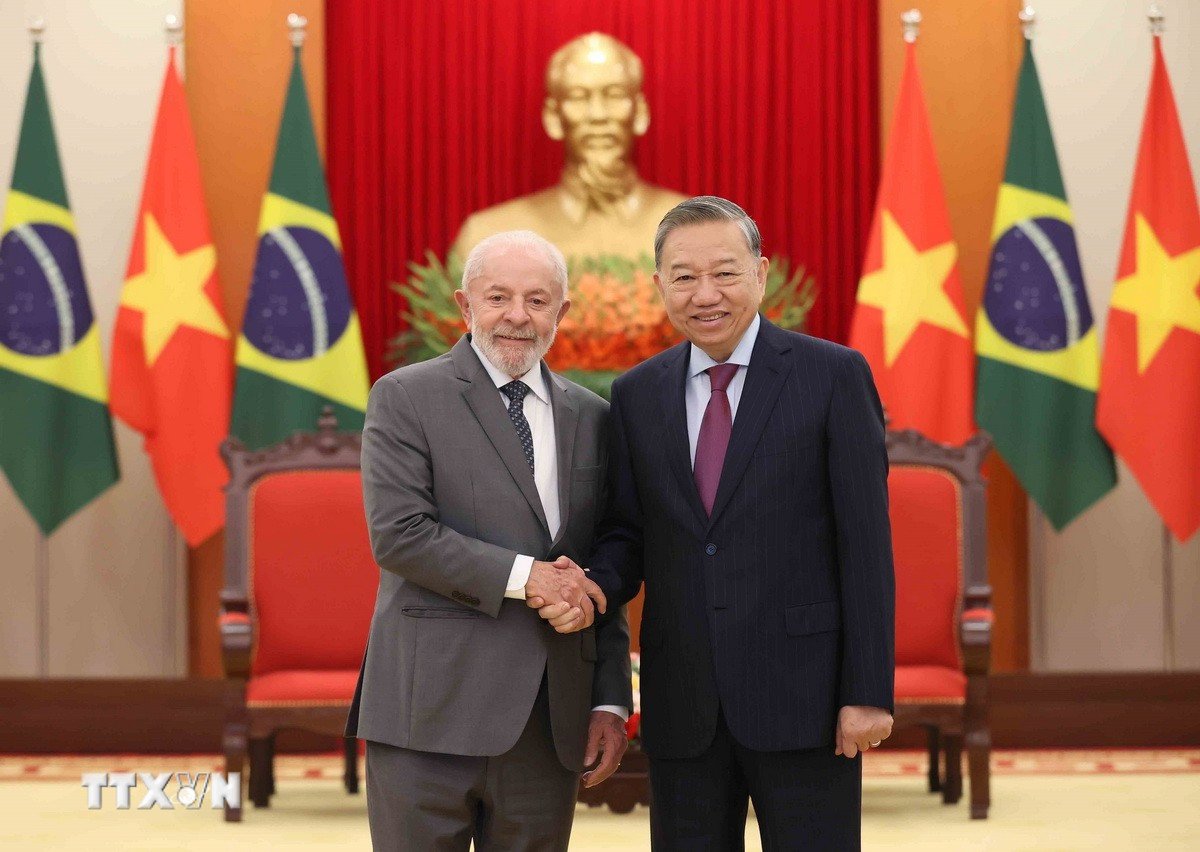

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam receives Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/28/7063dab9a0534269815360df80a9179e)

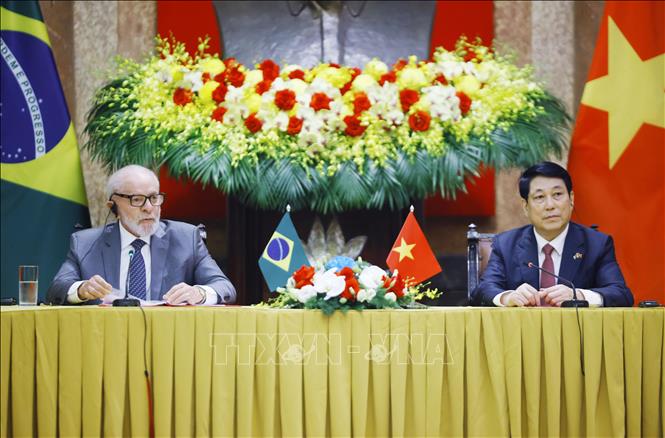

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh meets with Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/28/41f753a7a79044e3aafdae226fbf213b)

![[Photo] Helicopters and fighter jets practice in the sky of Ho Chi Minh City](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/28/3a610b9f4d464757995cac72c28aa9c6)

![[Photo] Vietnam and Brazil sign cooperation agreements in many important fields](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/28/a5603b27b5a54c00b9fdfca46720b47e)

Comment (0)