In early 1954, after launching the Dien Bien Phu campaign, France, with the support of the US, poured in more than 11,800 troops, at its peak up to 16,200, accounting for nearly 10% of the Northern army, the amount of ammunition was 20% higher than the monthly consumption of this force.

Dien Bien Phu became an "impregnable fortress", a "giant porcupine" in the mountains and forests of the Northwest. General Henri Navarre, Commander-in-Chief of the expeditionary force in Indochina, believed that the Viet Minh could not concentrate more than two divisions and heavy artillery on the battlefield. Supplying food, ammunition and necessities to the fighting army for a long time, on roads constantly bombed by the French air force, was "impossible".

After summarizing the battles in the Northwest and Na San at the end of 1953, the Second Bureau (the intelligence department of the French army) calculated the carrying capacity of Vietnamese laborers and concluded: "The Viet Minh combat corps cannot operate for long periods in an area lacking food, more than 18 km away from the base area".

Confident that he would "crush" the Viet Minh if they intended to attack Dien Bien Phu, on Christmas Eve 1953, the Commander of the De Castries stronghold said: "We are only afraid that the Viet Minh will see that the Dien Bien Phu bait is too big. If they are too afraid to attack, it will be a disaster for the soldiers' morale!". He ordered planes to drop leaflets, challenging General Vo Nguyen Giap and the troops.

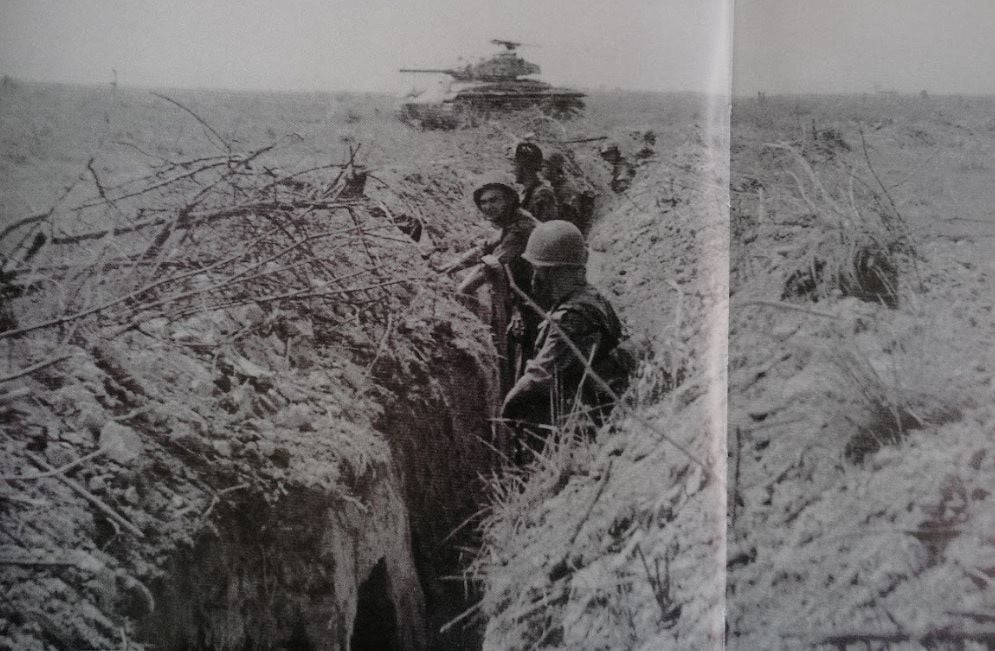

Accepting to fight the French, the Vietnam People's Army (called Viet Minh by the French) saw the challenges when launching the Dien Bien Phu campaign. The battle line alone at its peak needed more than 87,000 people, including 54,000 soldiers and 33,000 laborers. The amount of rice needed for this line was 16,000 tons.

Major General Nguyen An, former Deputy Director of the General Department of Logistics, once said that the supply source from the south was Thanh Hoa, a route of more than 900 km, so for every kilogram of rice that reached the destination, there had to be 24 kilograms of rice to eat along the way. In the Dien Bien Phu campaign, if it had to be transported entirely by foot, then to have 16,000 tons of rice reach the destination, it would have to be multiplied by 24 times, meaning that 384,000 tons of rice needed to be mobilized from the people.

"To have 384,000 tons of rice, we must collect and organize the milling of 640,000 tons of paddy. Assuming that even if we collect it, we cannot transport it in time because the distance is too far and the volume is too large," General Nguyen An said in the book Dien Bien Soldiers Tell Stories.

The campaign required 1,200 tons of weapons, including over 20,000 artillery shells, weighing 500 tons in total. In addition, explosives, medicine, military supplies, etc. had to be transported, all of which were not gathered in one place but scattered throughout the country. How could a large quantity of rice and ammunition be mobilized and transported to the front when there were only a few hundred cars?

Mobilizing rice on the spot, using bamboo to weave rice mills

With the spirit of "all for the frontline", the Politburo and the Government encouraged the people of Son La and Lai Chau, the two newly liberated provinces, to contribute rice to the army, minimizing the need for long-distance transportation. If rice aid from China had to be requested, the nearest source would be chosen, and if there was a shortage, it would be taken from farther rear areas.

As a result, the people of Son La and Lai Chau contributed more than 7,360 tons of rice, equal to 27% of the total mobilized amount. China's rice aid from Yunnan was 1,700 tons and the logistics sector purchased 300 tons of rice in the Nam Hu region (Upper Laos). The remaining 15,640 tons of rice had to be transported from the rear, of which 6,640 tons were supplied to the front. The amount of rice eaten along the way was only 9,000 tons, or only 2.4% of the initial calculation.

Colonel Tran Thinh Tan, a former platoon leader of the General Department of Forward Supply, said that the people of the Northwest contributed more than 10,000 tons of upland rice to the troops. This food source was very valuable because it was mobilized locally, but how to mill it into rice was a difficult question.

After many days of research, the General Department of Forward Supply decided to establish a "deputy mortar army" specializing in grinding rice right on the battlefield. The "deputy mortars" were recruited from army units, laborers, and sent from the rear. They went into the forest to cut bamboo to weave ropes to make mortar covers, split bamboo strips to make wedges, and used bamboo as rods. At first, the rate of rice milled by bamboo mortars was low, but later it increased.

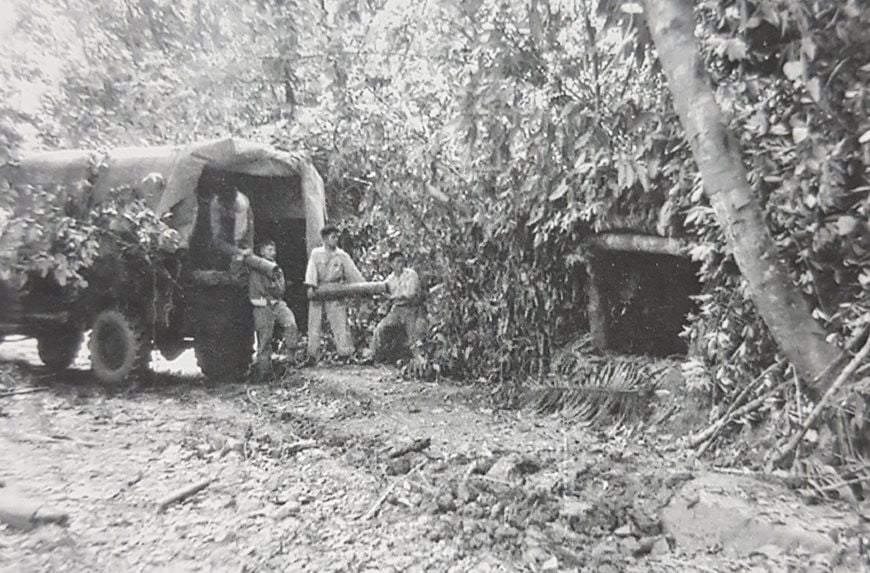

To transport rice and weapons to the battlefield, the Government mobilized laborers who were farmers in the liberated zone 4 (Thanh - Nghe - Tinh) and the temporarily occupied area, a total of 261,135 people, contributing nearly 11 million working days. From Son La to Dien Bien alone, there were 33,000 people, equivalent to 4.72 million working days. They participated in road construction, using shoulder poles, baskets, wheelbarrows, bamboo boats, bicycles, and even buffaloes and horses... to transport goods for the campaign.

The workers have modified ordinary bicycles into pack bicycles, which can climb steep slopes and carry hundreds of kilograms of goods. In total, the logistics sector mobilized nearly 21,000 pack bicycles, of which 2,500 were on the military route, each carrying an average of 180 kilograms, with Mr. Cao Van Ty's bike in Thanh Hoa carrying 320 kilograms and Mr. Ma Van Thang's bike in Phu Tho carrying 352 kilograms.

General Vo Nguyen Giap in the book Dien Bien Phu - Historical Rendezvous told about the atmosphere of the porters going to battle: "The pack-cart transport has become the second most important transport force, after the motor vehicle. The pack-horse groups of the Mong people from the highlands, the Tay, Nung, Thai, and Dao porters, add color to the endless continuous picture. There are also herds of swaggering cows, and trotting pigs, under the patient guidance of the supply soldiers, also going to the front."

General Navarre later had to admit: "In the area controlled by our army (ie the French army), the Viet Minh still had a secret authority. They collected taxes and recruited people. Here they transported a lot of rice, salt, fabric, medicine and even bicycles that were very useful in supplying...".

In addition to rudimentary means of transport, the Dien Bien Phu front was equipped with Soviet transport vehicles, at its peak 628 vehicles, including 352 vehicles for the military logistics line alone. The Viet Minh also used two waterways to transport goods: the Red River from Phu Tho, Vinh Phuc and the Ma River from Thanh Hoa to Van Mai, Hoa Binh province, then continued by road to Dien Bien Phu. Both of these routes mobilized up to 11,800 wooden boats and bamboo boats of all kinds.

Transporting from cannonballs to tobacco for the army

To attack Dien Bien Phu, artillery and ammunition played an important role. The Viet Minh had 105mm ammunition, but it was scarce while the quantity needed for the campaign was more than 20,000 rounds, with a total weight of 500 tons. Transporting these rounds to the artillery positions on steep mountain passes, under the control of the French air force, was a "brain-tightening" problem. Because 11,715 rounds had to be taken from the weapons depots in the rear, 500 to 700 km away from the front. This ammunition had been saved for 4 years, since the Border campaign in 1950.

Because of the scarcity, the protection of artillery shells was calculated in detail and carefully. The troops gathered ammunition in caves in Ban Lau, Son La province. At the front line, ammunition depots were dug deep into the mountainside, with wooden and plank lining along the road... Thanks to the discreet camouflage, although the French army continuously used reconnaissance planes to scout suspected locations of the warehouses, they were not discovered.

On the front line, troops parachuted 105mm ammunition that had been mistakenly dropped by French aircraft onto the battlefield, capturing more than 5,000 rounds. The Chinese army also contributed 3,600 rounds to the campaign, accounting for 18% of the total ammunition consumed.

In addition to ammunition, explosives, medicines, communication equipment, from radios to landline telephones, electric wires... were all carefully prepared by the logistics sector. The smooth information system helped the Campaign Command conveniently issue necessary orders.

According to the memoirs of Major General Nguyen Minh Long, former Deputy Director of the Operations Department, Assistant Staff in the Dien Bien Phu Campaign Command, to overcome the shortage of electric wires, the troops removed all communication wires from the Command to the agencies and the rear to replace them with bare wires, borrowing wires from the post offices of Son La, Lai Chau, and Hoa Binh. The Department launched a guerilla campaign in the enemy's rear to remove the wires of the French army, and sent troops to the Na San base to dig up the wires left behind by the enemy and bring them to Dien Bien Phu for use.

The logistics sector prepared every little thing for the troops. In the book Some Memories of Dien Bien Phu , Senior Lieutenant General Hoang Cam, then Commander of Regiment 209, Division 312, said that General Vo Nguyen Giap directed the supply sector to prepare enough tobacco, which most of the troops smoked.

General Cam explained that tobacco was not a basic issue in combat but was an indispensable practical need. The majority of soldiers at that time were farmers, many of whom were heavily addicted to tobacco, and once addicted, they would "bury their pipes and dig them up again". Without tobacco to smoke, people were depressed.

"Understanding that need, the Government and Uncle Ho instructed the rear to pay attention to providing the troops with tobacco to send to the front, along with guns, ammunition, rice, salt and medicine. But due to the prolonged fighting, the lack of tobacco was still a topical issue mentioned every day," General Hoang Cam recounted.

In the conditions of the resistance war, the Army Medical Corps had stockpiled medicines to treat wounded soldiers, including French wounded soldiers who had been taken prisoner. Before the day of total victory, the Army Medical Corps built a lime kiln on site to prepare lime powder to clean the battlefield and disinfect the trenches where the French troops were stationed. Just a few days after the end of the campaign, the battlefield was free of foul odors.

French General Yves Gras wrote in his book History of the Indochina War : "Mr. Giap believed that an entire nation would find a solution to the logistical problem and this solution defeated all calculations of the French General Staff...".

The Commander-in-Chief of the expeditionary army in Indochina also had to admit: "The Viet Minh Command has outlined their logistics work very well. We must acknowledge the great efforts of their people to support their army and admire the ability of the Command and the enemy Government to know how to achieve efficiency."

And French military historian, Dr. Ivan Cadeau, in the book Dien Bien Phu March 13 - May 7, 1954 , summarized all the documents archived in the French Ministry of Defense and concluded: "The French air force never succeeded in hindering the logistics of the Viet Minh, even for a few hours."

The strength of the logistics army contributed to the victory of Dien Bien Phu on May 7, 1954.

Source

Comment (0)