|

| Hotter weather due to climate change makes land dry, affecting rice productivity. Photo: IRRI |

Rice is a staple food for more than half the world’s population. Many countries build strategic rice reserves to ensure food security, especially in times of crisis. For example, Japan recently released rice from its national reserves for the first time since the 2011 earthquake and tsunami disaster in response to market shortages and soaring prices. This underscores the important role rice plays in economic and social stability.

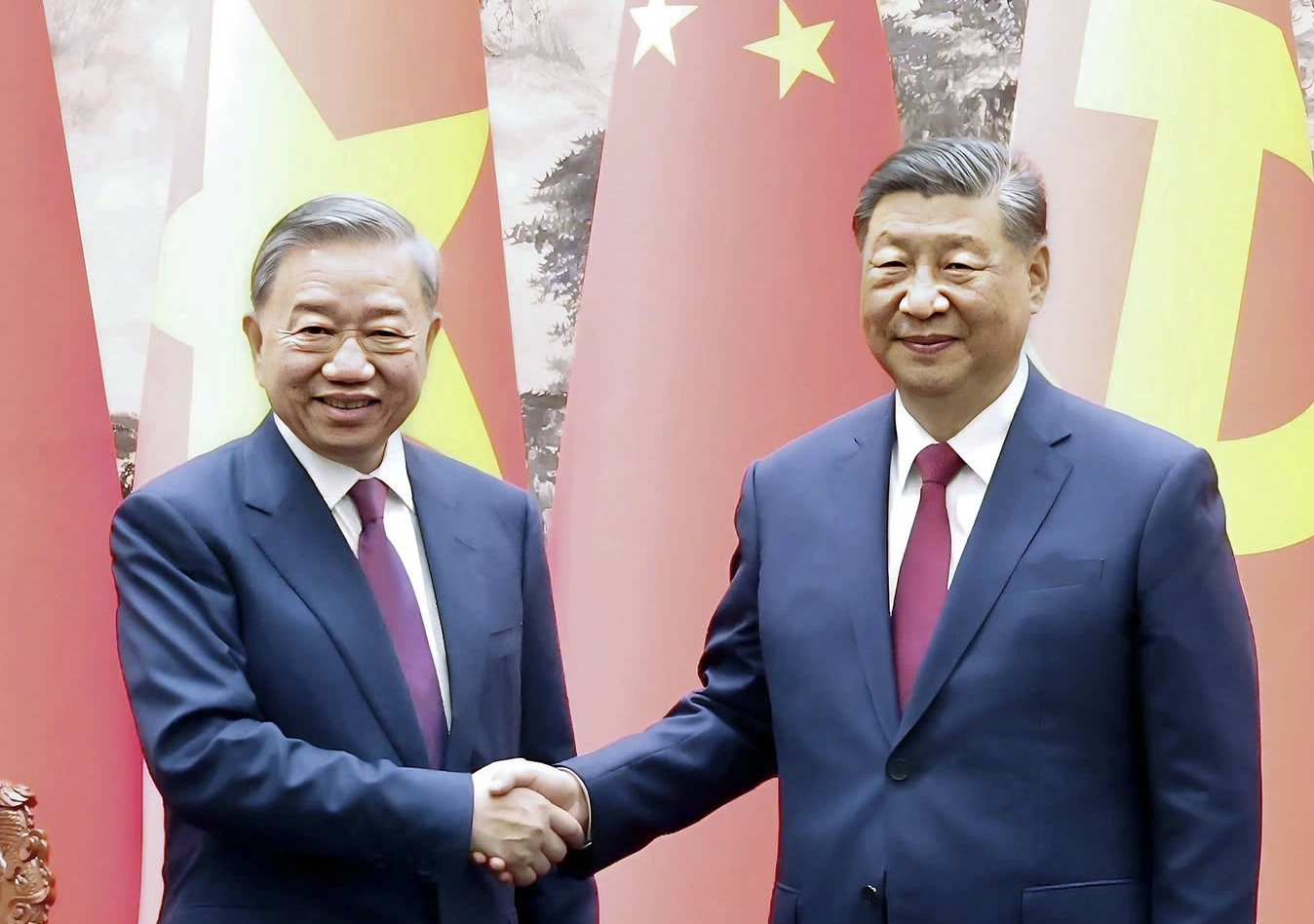

Many countries in Asia are racing to build self-sufficiency in rice. In early April, China released a 10-year agricultural plan to ensure domestic food security, emphasizing the role of rice in its long-term strategy.

Meanwhile, Indonesia has earmarked a vast area in its southern Papua province, the size of Jamaica, for new rice fields, part of an initiative announced late last year by Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto to expand rice cultivation by 1 million hectares in the country’s easternmost region.

The Indonesian government forecasts that the country’s 281 million people will consume more than 30 million tons of rice this year, so more rice production is needed. “Food is a matter of survival for our nation,” President Subianto said in February.

However, the 1 million hectare rice farming project in South Papua province is facing many doubts.

In a recent article in the journal Science, scientists warned that the project could fail due to poor soil quality, the relatively dry climate of Southern Papua, and the poor track record of similar past efforts to expand agricultural areas.

A 1990 project to convert mangrove land in Indonesia's Kalimantan region into rice paddies failed because the soil became too acidic after drainage and became unsuitable for cultivation. Another project in North Sumatra province to expand potato and onion cultivation was also abandoned because the volcanic soil was unsuitable for farming.

In addition, the Indonesian government has been accused of seizing land from indigenous communities to expand agricultural production, causing disputes over rights and social conflicts. Scientists warn that the new rice project in South Papua could cause new conflicts and long-term environmental damage.

Guy Kirk, professor of soil systems at Cranfield University in the UK and a member of the British Rice Research Consortium, said he understood these concerns.

“This is a typical tidal marsh area with acid sulfate soils, which can cause disaster if not managed properly,” he said of the new rice growing area in South Papua.

Meanwhile, the Indonesian government has said it will grow new rice varieties suited to soil and weather conditions if necessary.

A piece of land reclaimed for a project to expand the area for growing rice, sugarcane and other food crops in Maruke, South Papua province, Indonesia. Photo: AP

Breeding rice varieties that are adapted to local environments is an effective way to increase yields. Professor Guy Kirk estimates that global rice production will need to increase by 15-20%, while using less water and emitting less carbon, to meet demand in the coming decades, especially from Africa.

But climate change has made the rainy season wetter and the dry season drier, meaning rice yields are no longer reliable. Organizations like the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, which has branches across Asia and Africa, are developing rice varieties that are both drought- and flood-tolerant.

Scientific initiatives to improve rice productivity also face challenges. One prominent example is Golden Rice, a genetically modified rice designed to be fortified with vitamin A to reduce nutritional deficiencies in developing countries.

In 2021, the Philippines became the first country to allow commercial cultivation of Golden Rice. However, Greenpeace and local farmers sued against the decision, arguing that the new rice variety had not been proven safe.

Last year, an appeals court in the Philippines backed this argument and revoked the biosafety permit for commercial production of Golden Rice.

Optimizing rice farming management, through irrigation and fertilizer use, could also close the yield gap. A more radical solution, called the C4 Rice Project, aims to dramatically increase photosynthetic efficiency, a factor limiting rice yields. The project aims to engineer new photosynthetic pathways in rice. The project, launched in 2006, is funded by the Gates Foundation and involves 20 research teams from 15 institutions in eight countries.

One of Professor Guy Kirk’s projects to develop new rice varieties with partners in Germany and the US is currently on hold, due to sharp cuts in science budgets under President Donald Trump. Renowned research institutes such as IRRI, which developed the world’s first high-yielding rice variety, IR8, are also struggling as foreign aid dwindles.

Professor Kirk said this was “bad news for science”, especially as the world continues to face climate change, water scarcity and conflicts in the coming years as more mouths are fed due to population growth.

( According to thesaigontimes.vn )

Source: https://baoapbac.vn/kinh-te/202504/tuong-lai-bat-on-cua-hoat-dong-san-xuat-lua-gao-1039531/

![[Photo] Children's smiles - hope after the earthquake disaster in Myanmar](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/9fc59328310d43839c4d369d08421cf3)

![[Photo] Opening of the 44th session of the National Assembly Standing Committee](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/03a1687d4f584352a4b7aa6aa0f73792)

![[Photo] Touching images recreated at the program "Resources for Victory"](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/99863147ad274f01a9b208519ebc0dd2)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam chairs the third meeting to review the implementation of Resolution No. 18-NQ/TW](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/10f646e55e8e4f3b8c9ae2e35705481d)

Comment (0)