The growing global influence of BRICS positions the group as a key player in future global governance as a new era of international relations unfolds.

|

| The BRICS Summit and the BRICS Summit are taking place in Kazan, Russia. (Source: Reuters) |

On October 20, The Japan Times , Professor Brahma Chellaney at the Center for Policy Research based in New Delhi (India), and also a researcher at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin (Germany), wrote an article "The Rise of BRICS and an Emerging Multipolar World". Below is the content of the article:

A new era of international relations is dawning. With the West’s share of global GDP shrinking and the world becoming increasingly multipolar, countries are competing to assert their place in the emerging order.

This includes both emerging economies, represented by the expanded BRICS group of leading emerging economies, which are seeking a leadership role in setting the rules of the new order, and smaller countries that are trying to strengthen ties to protect their interests.

The appeal of BRICS

From a group of economies, BRICS has become a symbol of aspirations for a more representative and open global order, a counterweight to Western-led institutions, and a tool for navigating growing geopolitical uncertainty. All of this has proven to be attractive.

Earlier this year, BRICS expanded from five countries (Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa) to nine (plus Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates). And nearly 30 more countries, including NATO member Turkey; close U.S. partners Thailand and Mexico; and the world’s largest Muslim nation, Indonesia; have also applied to join BRICS.

While the diversity of members (and candidates) in the group highlights the broad appeal of BRICS, it also creates challenges. The group includes countries with very different political systems, economies, and national goals. Some even disagree with each other on a number of issues.

Harmonizing shared interests into a common plan of action and becoming a unified force on the international stage is difficult, even with only five members. With nine member states, and possibly more, establishing a common identity and agenda will require sustained effort.

Other multilateral groupings that are not formal, charter-based organizations with permanent secretariats, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Group of 20 (G20) or even the Group of Seven (G7), have also struggled with internal divisions.

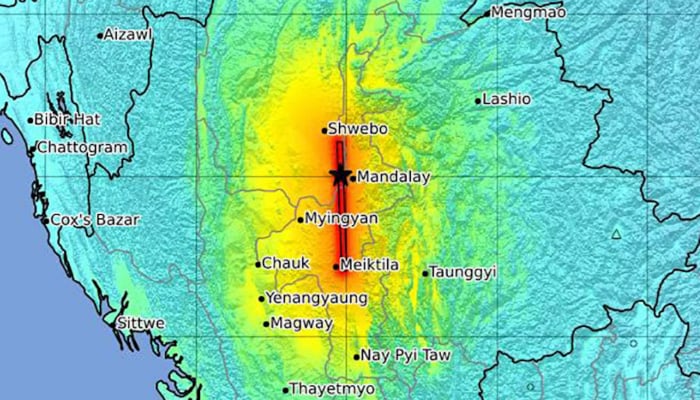

Moreover, BRICS has demonstrated remarkable adaptability and resilience. Some Western analysts predicted from the beginning that the group would disintegrate or fade into oblivion. However, the ongoing BRICS Summit and BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia – the first since the group’s expansion – have confirmed the group’s continued growth and may spur further expansion of BRICS.

Significant challenges

This is not to say that BRICS underestimates the challenge of cohesion. Even the group’s founding members may not agree on the basic goals of BRICS, whether to directly challenge the Western world order or to seek to reform existing international institutions and avoid any anti-Western bias.

Given this disagreement, enlargement could tip the balance. Six of the nine members, including the four newcomers, are formally part of the non-aligned movement, and two (Brazil and China) are observers. This suggests there will be considerable internal pressure on BRICS+ to chart a middle course, focused on democratizing the global order rather than challenging the West.

When it comes to fostering mutual trust with developing countries, the West has been at a disadvantage lately. The weaponization of finance and the seizure of interest earned on frozen Russian central bank assets has caused deep unease in the rest of the world.

As a result, more and more countries appear interested in considering alternative arrangements, including new cross-border payment mechanisms, with some also reassessing their reliance on the US dollar for international transactions and as a reserve asset.

All of this could play into the larger plans of Russia and China, the West’s two competitors. China would benefit, for example, from the growing international use of the CNY. Russia currently generates the bulk of its international export earnings in CNY and stores them largely in Chinese banks, essentially handing China a cut of the profits. China’s ultimate goal, which the West’s financial warfare inadvertently supports, is to establish an alternative financial system based on the CNY.

BRICS has been involved in institution building, establishing the New Development Bank (NDB) founded by India and headquartered in Shanghai in 2015. Not only is the NDB the world’s first multilateral development bank founded and led by emerging economies, it is also the only bank whose founding members are equal shareholders with an equal voice, even as more countries join.

The expansion of the BRICS has increased its formidable global influence. The group dwarfs the G7, both demographically (with nearly 46% of the world’s population, compared to the G7’s 8.8%) and economically (accounting for 35% of global GDP, compared to the G7’s 30%).

The economies of these grouping members are also likely to be the most important source of future global growth. Moreover, with Iran and the UAE joining their oil-producing partners Brazil and Russia, the expanded BRICS now account for about 40% of crude oil production and exports.

Fundamentally, the BRICS face significant challenges, not least in uniting to become a meaningful global force with defined political and economic goals, although the group holds potential to act as a catalyst for a global governance reform that better reflects the realities of the 21st century.

Source: https://baoquocte.vn/gia-tang-suc-nong-brics-duoc-dinh-vi-la-nhan-to-chu-chot-trong-quan-tri-toan-cau-tuong-lai-291180.html

![[Photo] Schools and students approach digital transformation, building smart schools](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/29/9ede9f0df2d342bdbf555d36e753854f)

![[Photo] Unique Ao Dai Parade forming a map of Vietnam with more than 1,000 women participating](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/29/fbd695fa9d5f43b89800439215ad7c69)

![[Photo] Brazilian President visits Vietnam Military History Museum](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/3/29/723eb19195014084bcdfa365be166928)

Comment (0)