The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recently announced that the world's richest countries have finally met their annual target of funding $100 billion for the energy transition by 2022.

In fact, the good news is that funding has already exceeded the target, by more than $15 billion, the OECD said. But these numbers are ultimately a drop in the bucket, as the ultimate goal of mobilizing trillions of dollars in green finance over the next few decades remains as elusive as ever.

Often referred to as climate finance, the amount of money that various forecasting agencies say the world needs to spend each year to switch from hydrocarbons to alternative energy sources is certainly not a small figure.

In fact, the price of the transition has been rising steadily over the past few years. In other words, by the time the OECD reaches its annual climate finance target of $100 billion, it will still not be enough to fuel the planned transition. And the figure could continue to rise.

The world needs to find and invest $2.4 trillion annually in the energy transition by 2030, Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), said earlier this year.

“It is clear that to achieve this transition we need money and lots of money, if not more,” Mr. Stiell said at the time.

What remains unclear is where that money will come from. Not only that, it has recently emerged that rich countries – who are supposed to shoulder the burden for all the poor countries that can’t afford to spend billions on solar and electric vehicle subsidies – have taken advantage of climate finance mechanisms.

Photo caption

An investigation by Stanford University's Big Local News journalism program has revealed that G7 members of the OECD routinely provide “climate finance” to poor countries in the form of loans rather than grants, with market interest rates rather than the typical discount rates for such loans.

Loans also come with strings attached, such as: The borrowing country must hire companies from the lending country to carry out the funded project.

The survey did not make a big splash. But as countries discuss raising climate finance investment targets ahead of the 29th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) scheduled to take place in Azerbaijan in November, the costs of the transition are also rising.

According to a recent Reuters overview of the current situation, Arab countries have proposed an annual investment target of $1.1 trillion, of which $441 billion would come from developed countries. The proposal to invest more than $1 trillion annually has also received support from India and African countries.

It makes sense that the potential beneficiaries of that trillion-dollar annual windfall would support the idea. But the parties who have to contribute to the plan are reluctant to sign on to anything when they themselves are strapped for cash.

There is no G7 country that is not in some form of financial trouble right now. From America's massive debt, Germany's near-zero GDP growth, to Japan's budget deficit, the G7 is in trouble.

The G7, however, is expected to shoulder most of the climate finance burden. The US and EU have agreed that they need to mobilize more than $100 trillion annually to give the transition a chance. “How” remains the trillion-dollar question.

One viable funding channel is private finance. But governments cannot guarantee returns that are sufficient to attract investors, making them reluctant to participate in the transition to provide the billions of dollars needed for climate finance.

Electric cars are a case in point. The EU has been doing everything it can to support electrification, including tax incentives for buyers, punitive taxes on owners of internal combustion engine vehicles, and heavy spending on charging infrastructure for electric vehicles.

But as governments begin to phase out subsidies for electric vehicles, sales are falling. Without making electric vehicles mandatory, the EU really has no choice.

Solar and wind power in the United States are another case in point. Installed capacity is growing rapidly across the country, but local community opposition to the installation of these facilities is also growing.

In February, USA Today reported on a survey that found that 15% of U.S. counties had stopped construction of large-scale wind and solar projects. While the article portrayed the trend as negative, affected communities often had pretty good reasons to object, such as environmental damage or energy reliability issues.

According to the United Nations, the world needs to spend $2.4 trillion annually to keep the average global temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2050.

The cost of the transition has increased by 19%, or $34 trillion, from previous estimates, according to BloombergNEF. How those responsible found the money and how it was distributed remains an unsolved mystery .

Minh Duc (According to Oil Price)

Source: https://www.nguoiduatin.vn/finance-for-global-energy-change-cau-cau-hoi-nghin-ty-usd-a669140.html

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh works with state-owned enterprises on digital transformation and promoting growth](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/f55bfb8a7db84af89332844c37778476)

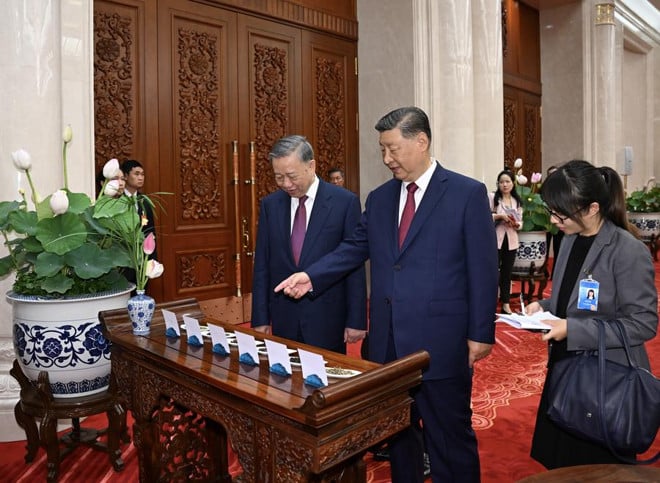

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong holds talks with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/f7e4c602ca2f4113924a583142737ff7)

![[Photo] Celebrating the 70th Anniversary of Nhan Dan Newspaper Printing House](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/a7a2e257814e4ce3b6281bd5ad2996b8)

![[Photo] Vietnamese and Chinese leaders attend the People's Friendship Meeting between the two countries](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/7d45d6c170034d52be046fa86b3d1d62)

![[Photo] Tan Son Nhat Terminal T3 - key project completed ahead of schedule](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/85f0ae82199548e5a30d478733f4d783)

Comment (0)