Thousands of years ago, the area was a lush savanna, with trees, lakes and rivers that supported large animals such as hippos and elephants. It was also home to primitive human communities, including 15 women and children found buried in a rock shelter by archaeologists. They subsisted on fishing and herding sheep and goats.

“We started with these two skeletons because they were so well preserved – the skin, the ligaments, the tissues were still intact,” said study co-author Savino di Lernia.

This is the first time archaeologists have sequenced the entire genome from human remains in such a hot and arid environment, according to di Lernia, associate professor of African archaeology and ethnoarchaeology at Sapienza University of Rome.

Genome analysis revealed a big surprise: the inhabitants of the Green Sahara were a previously unknown population that had lived in isolation for long periods of time and may have been in the region for tens of thousands of years.

Excavation of the Takarkori rock shelter, a site only accessible by four-wheel drive, began in 2003. Two female mummies were among the first discoveries.

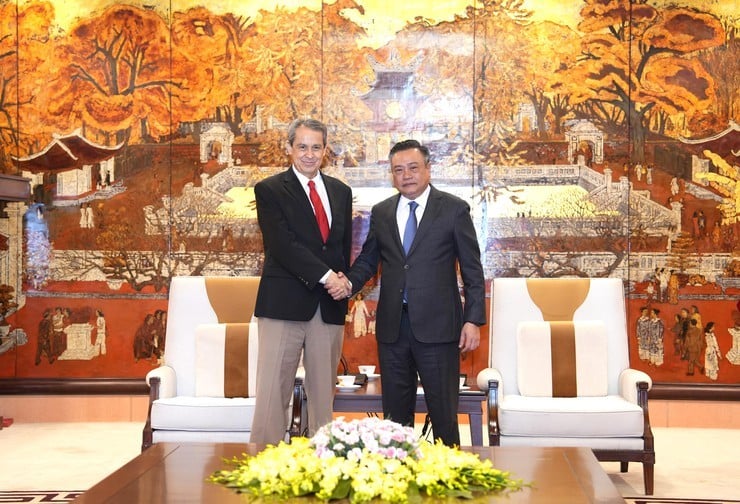

The mummies of two 7,000-year-old women, found in the Takarkori rock shelter. (Photo: Archaeological Mission in the Sahara/Sapienza University of Rome)

The small community that once lived there may have migrated here with the first wave of humans out of Africa more than 50,000 years ago. It is rare to find such a distinct genetic lineage, especially compared to Europe, where there is more genetic mixing, said study co-author Harald Ringbauer.

This genetic isolation suggests that the Sahara was not a migration corridor between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa at that time, despite the relatively favorable living conditions. Previously, researchers speculated that the Saharan inhabitants were pastoralists migrating from the Near East, where agriculture originated.

However, the new study refutes this hypothesis, showing that the Takarkori group showed no signs of genetic mixing with outside communities. Instead, herding may have been introduced through cultural exchange, thanks to interactions with other groups that had domesticated animals.

Their genetic lineage traces back to the Pleistocene period, which ended about 11,000 years ago. Louise Humphrey, a researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, agrees. She says the DNA of two female herders buried at Takarkori about 7,000 years ago suggests they belong to a previously unknown ancient North African lineage.

Ha Trang (according to Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, CNN)

Source: https://www.congluan.vn/xac-uop-tiet-lo-bi-mat-ve-qua-khu-cua-sa-mac-sahara-post341357.html

![[Photo] Closing of the 11th Conference of the 13th Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/12/114b57fe6e9b4814a5ddfacf6dfe5b7f)

![[Photo] Overcoming all difficulties, speeding up construction progress of Hoa Binh Hydropower Plant Expansion Project](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/12/bff04b551e98484c84d74c8faa3526e0)

Comment (0)