Researchers have discovered large amounts of water trapped inside the sediments and rocks of a lost volcanic plateau, now deep within the Earth's crust.

Geological imaging equipment dragged behind a research vessel during a survey of the Hikurangi subduction zone in New Zealand. Photo: Adrien Arnulf

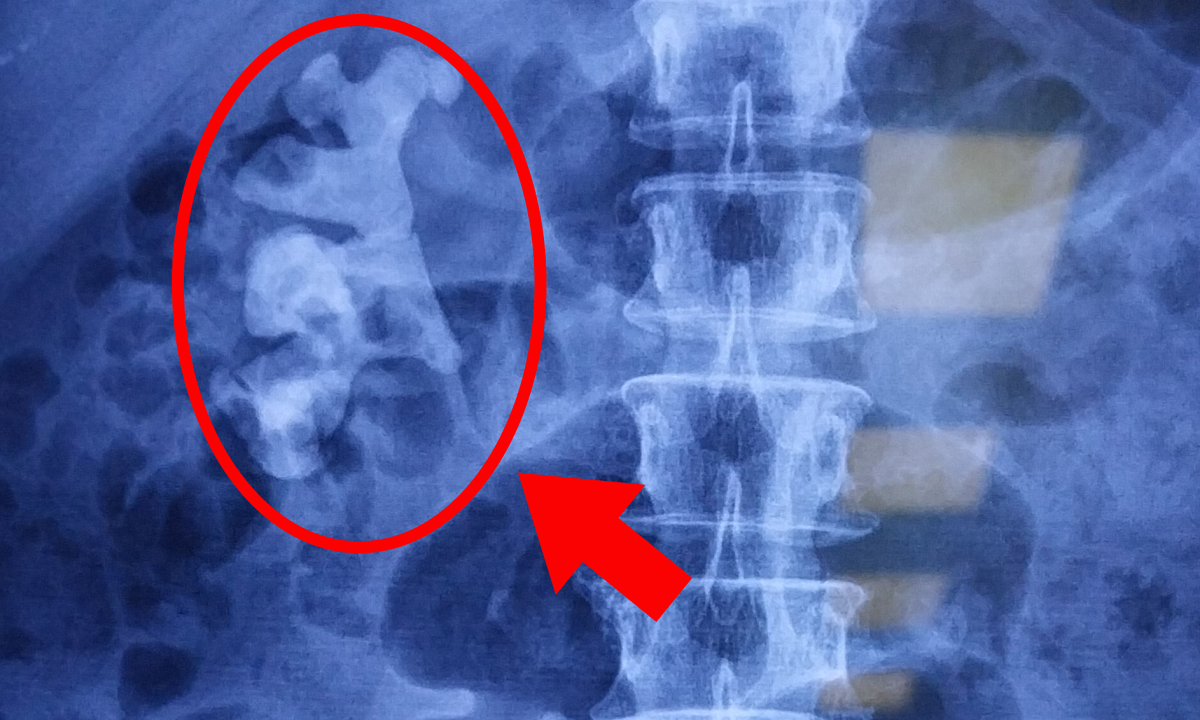

Revealed through 3D seismic imaging, the ancient reservoir lies 3.2 kilometers below the ocean floor off the coast of New Zealand, where it may be dampening a major earthquake fault opposite the North Island, Phys.org reported on October 8.

Faults often produce slow-moving earthquakes, called slow-slip events. These can release tectonic stress harmlessly over days and weeks. Scientists want to know why they occur more frequently on some faults than others. Many slow-slip earthquakes are thought to be associated with buried water. However, until now, there had been no direct geological evidence that such a large reservoir of water existed on the New Zealand fault.

“We can’t look deep enough to know exactly what’s affecting the fault, but we can see that the amount of water that’s accumulating here is much higher than usual,” said study leader Andrew Gase, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, is based on seismic surveys and ocean drilling conducted by the UTIG team. Gase, now a postdoctoral fellow at Western Washington University, calls for deeper drilling to find out where the lake ends so researchers can determine whether it affects the pressure around the fault. That’s important information for better understanding large earthquakes.

The site where the researchers found the lake is part of a vast volcanic field that formed when a lava column the size of the United States rose to the surface of the Pacific Ocean 125 million years ago. The event was one of the largest volcanic eruptions on Earth and caused tremors for millions of years. Gase used seismic scanning to build a 3D image of the ancient volcanic plateau, which showed that the sediments around the buried volcano were mostly thick. Gase’s UTIG colleagues tested a drill core sample of the volcanic rock and found that water made up nearly half of its volume.

Gase speculates that the shallow sea where the eruption occurred eroded part of the volcano into hollow rock that stored water as an aquifer. Over time, the rock and debris transformed into clay that accumulated even more water. The new finding is important because the researchers think that underground water pressure may be the key factor that creates the conditions for tectonic pressure to be released through slow-slip earthquakes. This usually happens when water-rich sediments are buried along a fault, trapping water underground. However, the New Zealand fault contained very little of this common type of ocean sediment. Instead, the team thinks that the ancient volcano and the clay-transformed rock carried large volumes of water as it was swallowed by the fault.

An Khang (According to Phys.org )

Source link

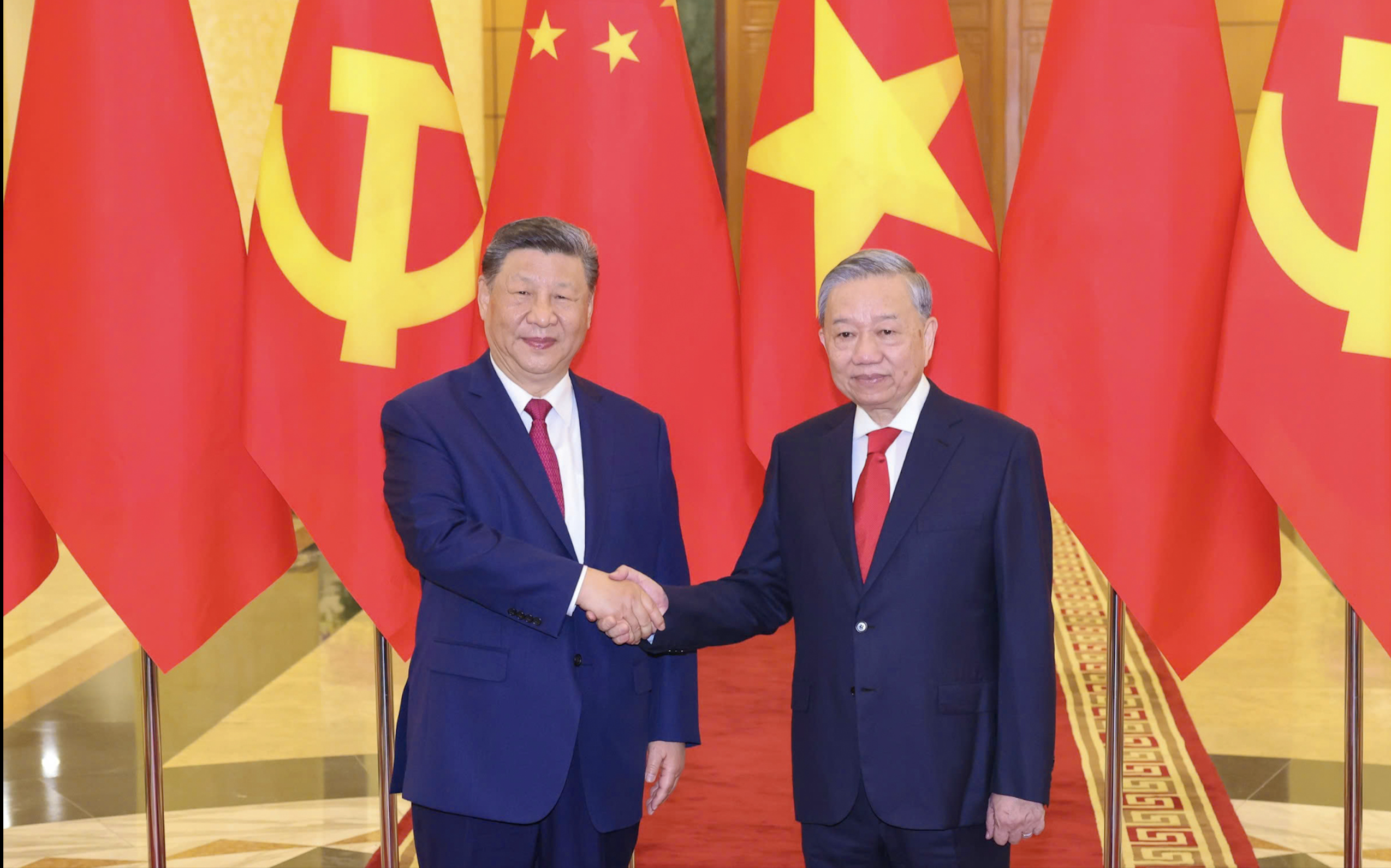

![[Photo] Reception to welcome General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/ef636fe84ae24df48dcc734ac3692867)

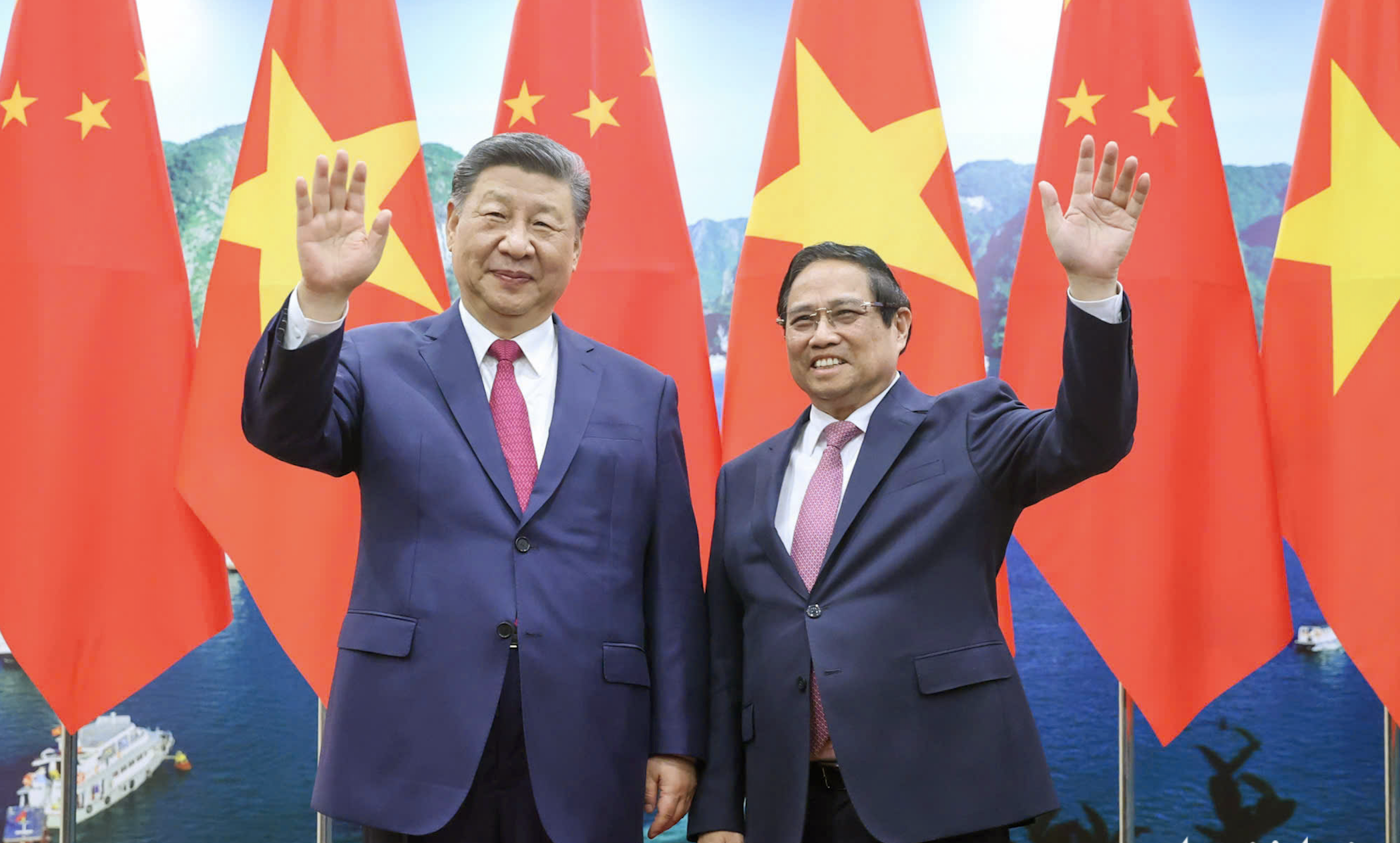

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh meets with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/893f1141468a49e29fb42607a670b174)

![[Photo] Tan Son Nhat Terminal T3 - key project completed ahead of schedule](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/85f0ae82199548e5a30d478733f4d783)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man meets with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/4e8fab54da744230b54598eff0070485)

Comment (0)