Former President Mikheil Saakashvili led the Rose Revolution to become Georgia's leader, but he is also a controversial politician.

Saakashvili appeared in a televised court hearing on July 3. He raised concerns among many when he lifted his shirt to reveal a skinny body, sunken stomach and gaunt face.

The former Georgian president said that despite his poor health, he was "still in good spirits and determined to serve his country". "A completely innocent man is in custody. I have not committed any crime," he said.

Saakashvili, 55, served as Georgia's president from 2004 to 2007 and from 2008 to 2013. He was convicted in absentia of abuse of office in 2018 and sentenced to six years in prison. Saakashvili denies this, saying the case was politically motivated and decided to flee to Ukraine to avoid arrest.

But the former Georgian president was arrested upon his return to the country in October 2021 and has been in prison ever since. He has staged several hunger strikes to protest the charges against him. Saakashvili is currently being held in a private hospital, where he was transferred last year after a 50-day hunger strike.

Saakashvili and his supporters believe he was poisoned. The 6ft 1in former president now weighs just 130lbs, half his pre-arrest weight. "Putting me in jail won't break me. I will still actively participate in Georgian politics," he said.

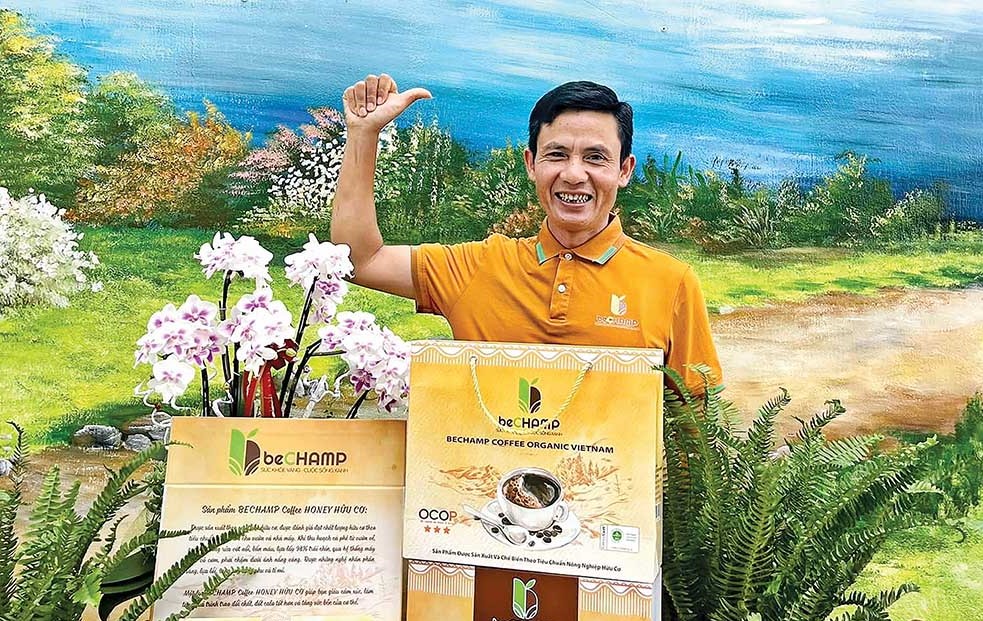

Former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili gives an interview at his home on the outskirts of Kiev, Ukraine, in 2020. Photo: Reuters

Saakashvili was born on December 21, 1967 in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. He graduated from the Faculty of Law of the Institute of International Relations of the University of Kiev, Ukraine, then continued his postgraduate studies in France, Italy, the Netherlands and Columbia University, USA. From 1993 to 1995, he worked for a law firm in New York.

Saakashvili later returned to Georgia at the invitation of Zurab Zhvania, then chairman of the Georgian Civic Union (SMK) party, and was elected to parliament in November 1995.

From 1995 to 1998, he served as chairman of the National Assembly's Legal Affairs Committee and lobbied unsuccessfully for faster and more comprehensive policy reforms.

In August 1998, he was elected head of the SMK party in parliament. In October 2000, he was appointed justice minister and embarked on reforms of the Georgian legal system and improved prison conditions. As a populist, he called for popular support in his efforts to crack down on corruption among high-ranking officials.

In August 2001, Saakashvili directly opposed President Shevardnadze and unexpectedly resigned after a mysterious burglary at his home. He was re-elected to parliament in the same year's elections and in October he founded the United National Movement (UNM) party. Saakashvili was then elected chairman of the Tbilisi city council. In this position, he implemented a policy of increasing pensions, donating textbooks to schools, and personally helping to repair dilapidated residential buildings.

On November 3, 2003, the Georgian government announced that the New Georgia party, which supports President Shevardnadze, had won the parliamentary elections.

Saakashvili, along with Zhvania and parliamentary speaker Nino Burdjanadze, led protests in Tbilisi and other cities, alleging that the vote was rigged and calling for Shevardnadze's resignation. Shevardnadze's approval ratings had fallen sharply since 2000 due to economic problems, poor management of basic services, and corruption in the state and security apparatus.

On November 22, 2003, Saakashvili and his supporters occupied the parliament building unopposed, holding roses. President Shevardnadze fled the building and announced his resignation the following day.

This protest movement is now remembered as the Rose Revolution. Saakashvili's pivotal role in the protests helped him to be elected president in 2004.

He immediately appointed a new government team to find solutions to Georgia's many problems and focused on tackling corruption. Most importantly, however, Saakashvili kept the country united in the face of separatist movements in regions such as Abkhazia, Ajaria and South Ossetia.

Saakashvili rose strongly in his first term as president, but a series of allegations of civil rights abuses and his increasingly hardline policies fueled widespread opposition movements.

Irakli Okruashvili, a former defense minister under Saakashvili, founded the Georgian Unity Movement party in 2007 and began making direct accusations against him.

Okruashvili was subsequently arrested, prompting opposition protests in late 2007. On 2 November 2007, some 50,000 people gathered outside the parliament building in Tbilisi to call for Saakashvili to resign.

Protests continued until 7 November 2007, when riot police were deployed to disperse the crowds and Saakashvili declared a 15-day nationwide state of emergency. After calling early elections, he resigned as president on 25 November 2007.

Saakashvili went on to win the presidential election in January 2008, but with a much smaller margin than in the 2004 election.

Soon after Saakashvili took office, the conflict between the Georgian government and the breakaway region of South Ossetia intensified. Georgian government forces fought local separatist fighters as well as Russian forces that had crossed the border. Russia said its aim was to protect Russian citizens and peacekeepers in the region.

Violence spread across the country as Russian forces moved through the breakaway region of Abkhazia in northwestern Georgia. Georgia and Russia later signed a French-brokered ceasefire. Russian forces withdrew from uncontested areas, but tensions persisted.

Saakashvili faced growing criticism. Opposition groups, who opposed Saakashvili's use of force during the November 2007 protests, disapproved of his handling of the tensions and accused him of plunging Georgia into a costly, brutal conflict that they could not win.

In 2012, Saakashvili's UNM party faced a challenge from the newly formed opposition coalition Georgian Dream (GD), led by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili.

In the weeks leading up to the October 2012 parliamentary elections, polls showed the UNM still leading the GD, but the party’s position was damaged when videos of Georgian prison guards beating and sexually abusing prisoners went viral, sparking public outrage. The UNM ultimately lost to the GD, and Saakashvili resigned in 2013.

After leaving office, Saakashvili briefly taught at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Georgian officials filed charges against him during this time, so he did not return to the country. In 2018, he was tried in absentia and convicted of abuse of power in two separate trials.

Saakashvili traveled to Ukraine in 2015 at the invitation of then-president Petro Poroshenko. Ukraine was under pressure to reform due to the conflict with pro-Russian separatists in the east, a situation similar to what Saakashvili faced during his second term as president. Saakashvili was granted Ukrainian citizenship, renounced his Georgian citizenship, and was appointed governor of Ukraine’s Odessa region.

The following year, he accused the Ukrainian president of corruption, resigned as governor, and formed an opposition party against Poroshenko. While Saakashvili was in the United States in June 2017, Poroshenko stripped him of his citizenship. Saakashvili returned to Ukraine via Poland but was arrested in February 2018 and deported back to Poland. Saakashvili moved to the Netherlands, where his wife has citizenship, and found work as a lecturer.

In 2019, Saakashvili returned to Ukraine after his citizenship was restored by President Volodymyr Zelensky. In May 2020, Zelensky appointed him head of the Ukrainian Reform Committee.

Weeks before Georgia’s 2020 parliamentary elections, Saakashvili announced his intention to return home. Despite being denied citizenship and facing the threat of imprisonment if he re-entered the country, the UNM nominated him as its candidate for prime minister. However, the UNM lost the election and Saakashvili remained in Ukraine.

In 2021, he returned to Georgia with the intention of calling on people to organize large-scale anti-government protests ahead of local elections in October. He was arrested just hours after announcing his return.

At home, Saakashvili is a controversial political figure, but even many of his opponents feel dissatisfied with the way the former Georgian president is being treated.

"There were systematic human rights violations under Saakashvili, but in a state of law you need to bring proper charges, not this," said Eka Tsimakuridze of the Georgian Democracy Index. "You can have serious political disagreements with Saakashvili but the risk of him dying in custody would be catastrophic for the country."

“If Saakashvili dies in prison, it will create a wound in Georgian society that will be difficult to heal,” she said.

Former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili appears in court in Tbilisi on July 3. Photo: Reuters

Ukrainian President Zelensky said on July 3 that Saakashvili was "being tortured", demanding that Tbilisi hand him over to Kiev. In addition to Ukraine, many other countries have also voiced their discontent about the conditions that former President Saakashvili is being subjected to.

"Torturing an opposition leader to death is unacceptable for a country that wants to join the European Union (EU)," Moldovan President Maia Sandu wrote on Twitter earlier this year, calling on Georgia to release Saakashvili immediately.

Late last year, Saakashvili wrote a handwritten letter to French President Emmanuel Macron, in which he wrote: "SOS. I am dying, I have very little time left."

However, Georgian authorities believe that Saakashvili is faking his health condition to get out of prison.

Vu Hoang (According to BBC, Guardian, Britannica )

Source link

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh receives Mr. Jefferey Perlman, CEO of Warburg Pincus Group (USA)](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/18/c37781eeb50342f09d8fe6841db2426c)

Comment (0)