An angry deal

The exact text of the agreement signed by the leaders of Ethiopia and Somaliland has not been made public. According to the BBC, there are different versions of what the two sides agreed to in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). And while the MoU is a statement of intent rather than a legally binding agreement, what seems clear is that Somaliland is willing to lease the port to Ethiopia.

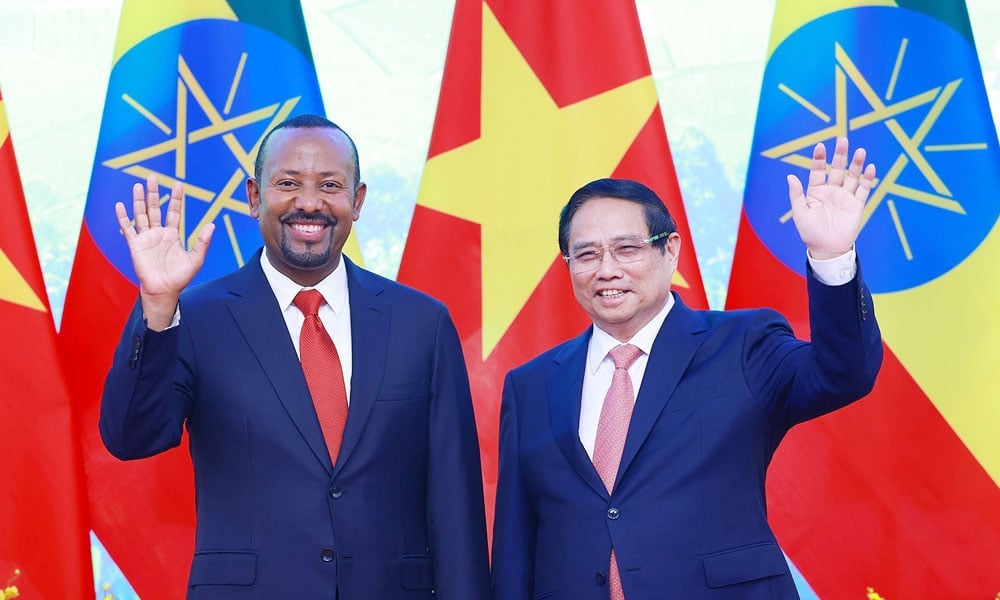

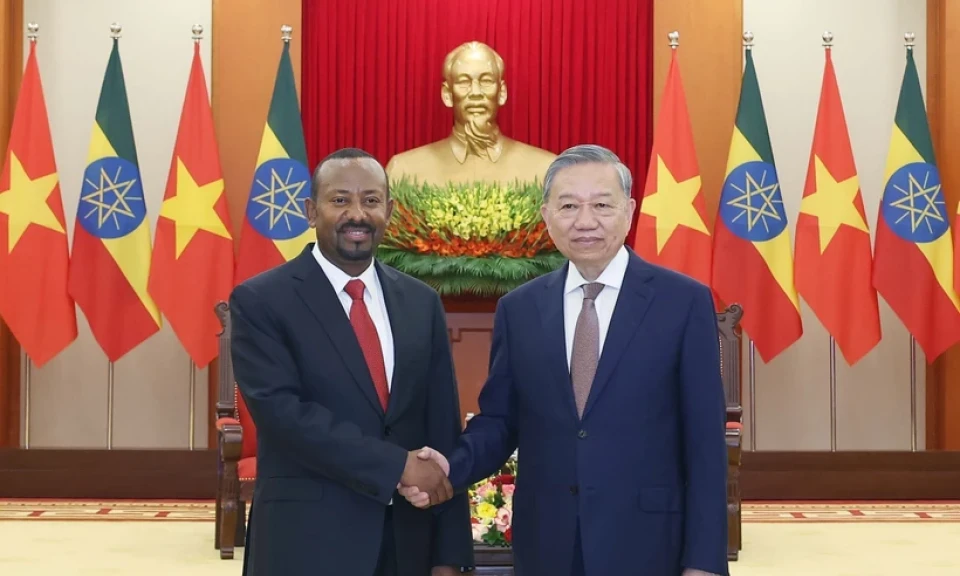

Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi (right) and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed at the signing ceremony of an agreement allowing Ethiopia to use Somaliland's seaport. Photo: Horn Observer

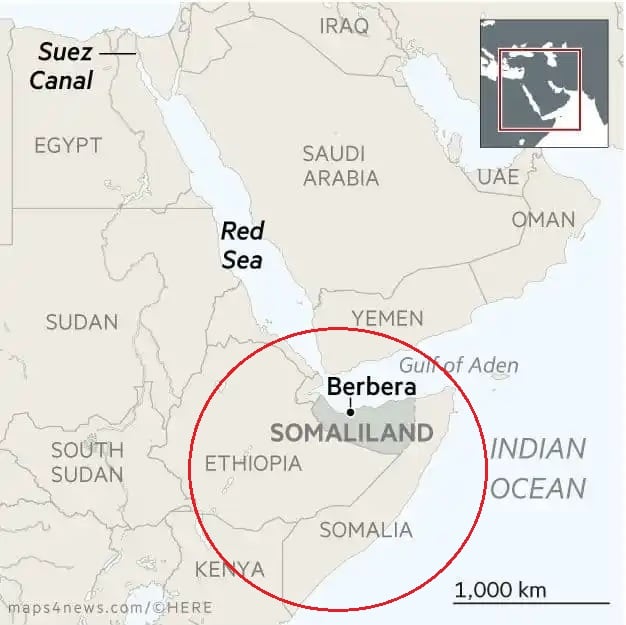

If Somaliland opens the way, Ethiopia, the world's most populous landlocked country, will gain access to Red Sea shipping lanes through the Bab al-Mandeb Strait between Djibouti (in the Horn of Africa) and Yemen (in the Middle East), and connect the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

There is also a military dimension: Somaliland has said it may lease a 20-kilometer stretch of its Red Sea coastline to the Ethiopian navy, a detail that has also been confirmed by Addis Ababa. In return, Somaliland will take a stake in Ethiopian Airlines, Ethiopia’s highly successful national airline.

On the day of the signing (January 1), Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi said the agreement included a section stating that Ethiopia would recognize Somaliland as an independent state at some point in the future.

However, Ethiopia has not confirmed this. Instead, in an attempt to clarify what is contained in the MoU, the Ethiopian government said on January 3 that the agreement only includes “provisions… to provide an in-depth assessment of the position taken in relation to Somaliland’s efforts to gain recognition.”

The rhetoric seemed very cautious. But it was enough to light the fire.

Somaliland declared independence from Somalia in 1991 and has all the trappings of a state, including a functioning political system, elections, a police force and its own currency. But Somaliland’s independence has not been recognized by any country. And so Somalia has reacted angrily to Ethiopia’s moves.

Somalia’s Foreign Ministry called the deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland a serious violation of Somalia’s sovereignty. It stressed that “there is no room for reconciliation unless Ethiopia withdraws its illegal agreement” with Somaliland and reaffirms the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The Somali government has asked both the African Union (AU) and the United Nations Security Council to convene meetings on the issue, and has recalled its ambassador to Ethiopia for urgent consultations. Speaking in the Somali parliament, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud firmly declared: “Somalia belongs to the Somali people. We will defend every inch of our sacred land and will not tolerate attempts to abandon any part of our homeland.”

Risk of further destabilization for the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea

The deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland immediately drew criticism from other neighboring countries, such as Djibouti - which still benefits from leasing the port to Ethiopia - and Eritrea and Egypt - countries concerned about the return of Ethiopia's navy to strategic waters: the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi strongly criticized Ethiopia's move and said Cairo stood by Somalia. "Egypt will not allow anyone to threaten Somalia or affect its security. Do not test Egypt or try to threaten our brothers, especially if they ask us to intervene," El-Sissi said while welcoming Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud to Cairo over the weekend.

Map of the Horn of Africa, located across the Red Sea from Yemen, with Ethiopia being the only landlocked country. Photo: GI

Relations between Egypt and Ethiopia have been troubled for more than a decade over the construction and operation of the Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a mega-infrastructure project that Ethiopia built on the Blue Nile, upstream of Egypt.

Negotiations between the two sides, along with neighboring Sudan, have so far failed to reach a consensus and Cairo continues to voice concerns about water security. Ethiopia’s agreement to lease a port from Somaliland has therefore deepened the conflict.

The African Union (AU) has also expressed concern over the deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland. The organization’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) issued a press release on Wednesday (17 January) saying: “The Council expresses its deep concern over the ongoing tensions… and their potential adverse impact on peace, security and stability in the region,” and called on Ethiopia and Somalia to “exercise restraint, de-escalate tensions and engage in meaningful dialogue to find a peaceful solution to the issue.”

Observers say the Ethiopian deal could be seen as a dangerous tinderbox for the Horn of Africa, already the world’s top hotspot for political unrest. It could also add to the turmoil in the Middle East and Red Sea, already rattled by the Gaza war and the US-Houthi attacks.

For decades, this 2 million square kilometer land has never been at peace. From the Ethiopian-Somalia wars of 1977-78 and 2006 to the civil war in Somalia that led to the secession of Somaliland in 1991, to the civil war in Sudan and the Eritrea–Ethiopian war that led to Eritrea’s separation from Ethiopia… bloody conflicts have left the Horn of Africa in ruins.

With a stagnant economy, frequent natural disasters and constant famine, the region has become a fertile ground for terrorist organizations and radical Islamic movements to take root. This can be seen clearly in Somalia, where over the past two decades, the country has been devastated by Al-Shabaab, an Al-Qaida affiliate that was formed in Somalia after Ethiopia invaded Somalia in 2006.

Now, if the conflicts that have just flared up between Ethiopia and Somalia turn into a war, the situation in the Horn of Africa will become even more dire, and at the same time make the anti-terrorism efforts of the major powers in this region more difficult.

During a press briefing last week, US National Security Council spokesman John Kirby also expressed concern that rising tensions between Somalia and Ethiopia could undermine broader efforts to combat terrorist groups operating in Somalia.

Why is Ethiopia taking the risk of pursuing the deal?

After Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia in 1993 and became an independent nation, Ethiopia was completely cut off from the ocean. With no access to the sea, Ethiopia had to use the port in neighboring Djibouti to transport about 95% of its imports and exports.

The $1.5 billion annual fee that Ethiopia pays to use Djibouti’s ports is a huge sum for a country struggling to service its massive debts. Access to the Red Sea is therefore seen by many Ethiopians as vital to the country’s development and security.

Somaliland's Berbera Port was almost bought by Ethiopia for 19% of its shares in 2018 - Photo: AFP

For years, the Ethiopian government has sought to diversify its access to ports, including exploration options in Sudan and Kenya. In 2017, Ethiopia bought a stake in the Berbera port in Somaliland as part of a deal involving leading UAE logistics group DP World to expand the port. Somalia also objected strongly at the time, leading Ethiopia to back out of its commitments and eventually lose its stake in 2022.

But in recent months, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has become more assertive about his country’s ambitions to acquire a port along the East African coast. Speaking on state television in October, Abiy Ahmed stressed that his government needed to find a way to free 126 million people from their “geographical prisons.”

The move is driven by Ethiopia’s economic woes, experts say. Just before the new year, U.S.-based rating agency Fitch put Ethiopia in “limited default” after the government in Addis Ababa defaulted on its Eurobond payments. Ethiopia is also in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over a bailout package to shore up its ailing economy.

Ethiopia's economic woes stem in part from a two-year war (2020-2022) in the country's northern Tigray province, where TPLF rebels have fought government troops in a conflict that has killed hundreds of thousands of people and displaced millions.

A year after the war ended, much has been destroyed, especially in agriculture. Famine threatens in Tigray and neighboring Amhara. The government in Addis Ababa estimates the cost of rebuilding these lands at $20 billion, a sum beyond their means.

Opening a new route to the Red Sea would thus not only provide Ethiopia with a trade outlet, but also shift some of the pressure outward. But the costs of this risky decision may lie ahead, and may be beyond the control of planners in Addis Ababa.

Nguyen Khanh

Source

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam receives French Ambassador to Vietnam Olivier Brochet](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/49224f0f12e84b66a73b17eb251f7278)

![[Photo] Promoting friendship, solidarity and cooperation between the armies and people of the two countries](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/0c4d087864f14092aed77252590b6bae)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man meets with outstanding workers in the oil and gas industry](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/1d0de4026b75434ab34279624db7ee4a)

![[Photo] Closing of the 4th Summit of the Partnership for Green Growth and the Global Goals](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/c0a0df9852c84e58be0a8b939189c85a)

![[Photo] Nhan Dan Newspaper announces the project "Love Vietnam so much"](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/362f882012d3432783fc92fab1b3e980)

![[Photo] Welcoming ceremony for Chinese Defense Minister and delegation for friendship exchange](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/fadd533046594e5cacbb28de4c4d5655)

![[Video] Viettel officially puts into operation the largest submarine optical cable line in Vietnam](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/17/f19008c6010c4a538cc422cb791ca0a1)

Comment (0)