(CLO) According to official statistics from the Indonesian Government, nearly 10 million people have left the country's middle class since 2019.

Halimah Nasution once felt as if she had it all. For years, she and her husband, Agus Saputra, made a comfortable living renting out props for weddings, graduations and birthdays.

Even after dividing the income among several siblings who help them with this work, the couple in Indonesia's North Sumatra province still earns about 30 million rupiah (nearly 50 million VND) per month.

Spending only about a quarter of their monthly income, the couple falls into Indonesia's middle class, officially defined as those with monthly spending between 2 million rupiah and 9.9 million rupiah.

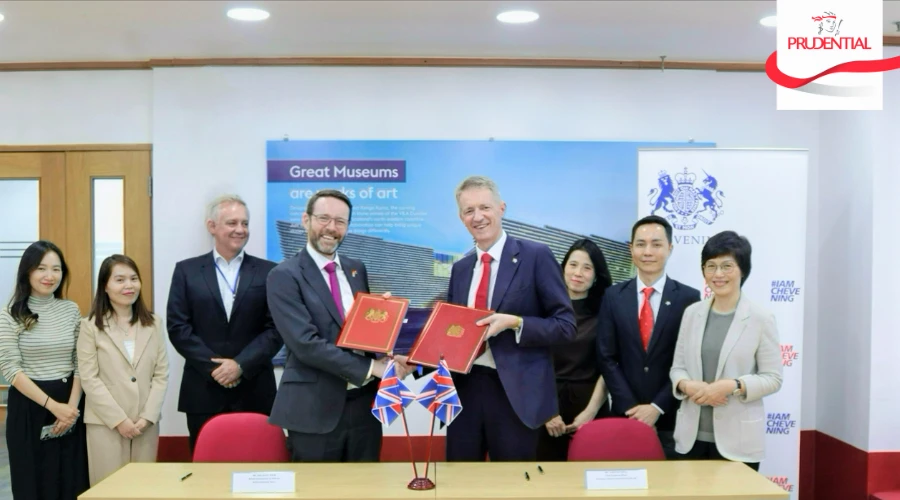

Millions of Indonesians have left the middle class in the past few years. Illustration photo: Reuters

From COVID to Global Uncertainty

But then came the COVID-19 pandemic. The lockdown was devastating. “We lost everything,” Nasution told Al Jazeera. Years later, the couple has yet to recoup their losses and revive their business.

They are among millions of Indonesians who have been pushed out of the Southeast Asian nation’s shrinking middle class. The number of Indonesians classified as middle class fell from 57.3 million in 2019 to 47.8 million this year, according to data from Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency.

Economists say the decline is due to a number of reasons, including the fallout from COVID-19, global uncertainty and shortcomings in the country's social safety net.

Ega Kurnia Yazid, a policy expert at the Indonesian government-run National Poverty Reduction Acceleration Team, said “a number of interconnected factors” contributed to the trend.

Indonesia's middle class “contributes the majority of tax revenue but receives less social benefits” than the poorer classes below, Yazid explained.

Nasution and her husband understood this lack of support well when their business collapsed. “We didn’t get any help from the government when we were no longer able to work during the pandemic…”, she said.

"The middle class is in a dilemma. We are not really rich, but we are not poor enough to receive subsidies that could benefit us," Dinar, a worker in Jakarta, told DW.

Research published in August 2024 by the Institute of Economic and Social Research (LPEM-UI) of the University of Indonesia shows that the purchasing power of the middle class and those aspiring to become middle class in Indonesia has decreased over the past five years. They now need to allocate more of their budget to food and therefore spend less on other things.

When the economy depends heavily on trade and services

Indonesia's economy has grown steadily since the pandemic ended, with annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth of about 5%. But like many developing countries, Southeast Asia's largest economy is heavily dependent on trade, making it vulnerable to a global slowdown.

“Major trading partners such as the US, China and Japan are experiencing a slowdown, as indicated by the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), leading to a decline in international demand for Indonesian goods… This puts additional stress on the middle class,” Yazid said.

Indonesians are spending more of their budget on food and less on other items. Illustration photo: Aman Rochman

Indonesia's stressed middle class "reflects deeper structural problems, particularly the impact of Indonesia's deindustrialization," said Adinova Fauri, an economics researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“Manufacturing, which once absorbed a large part of the workforce, can no longer do so. A significant part of the workforce has moved into the service sector, which is largely informal and offers lower wages and minimal social security,” Fauri said.

There are not many opportunities to start a business again.

The inauguration of President Prabowo Subianto last month raised hopes for the economy in some places. During his election campaign, he pledged to achieve 8% GDP growth and eradicate poverty.

However, at this time, Nasution and her family were still helpless in reviving their business. After buying many expensive items for work such as stages and decorations on installments, she and her husband quickly fell into poverty when the business failed.

“We sold our cars, sold our land, and mortgaged our house,” Nasution said. “It was dead. Our business was completely dead.”

Nasution’s husband had to find work harvesting oil palm fruit, earning about 2.8 million rupiah (nearly 5 million VND) a month. Meanwhile, Nasution took a cleaning job, working from 8am to 1pm, six days a week, for a monthly salary of about 1 million rupiah (1.6 million VND). Their once comfortable life is now a distant memory.

“Our lives are very different now, and we are not as stable as before. We need capital to start a business again, but we cannot save money to do so,” Nasution said. “We only have enough money to live on, but life is up and down, hopefully things will get better.”

Hoang Hai (according to AJ, DW)

Source: https://www.congluan.vn/chung-toi-da-mat-tat-ca-hang-trieu-nguoi-indonesia-roi-khoi-tang-lop-trung-luu-post321613.html

![[Photo] Tan Son Nhat Terminal T3 - key project completed ahead of schedule](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/85f0ae82199548e5a30d478733f4d783)

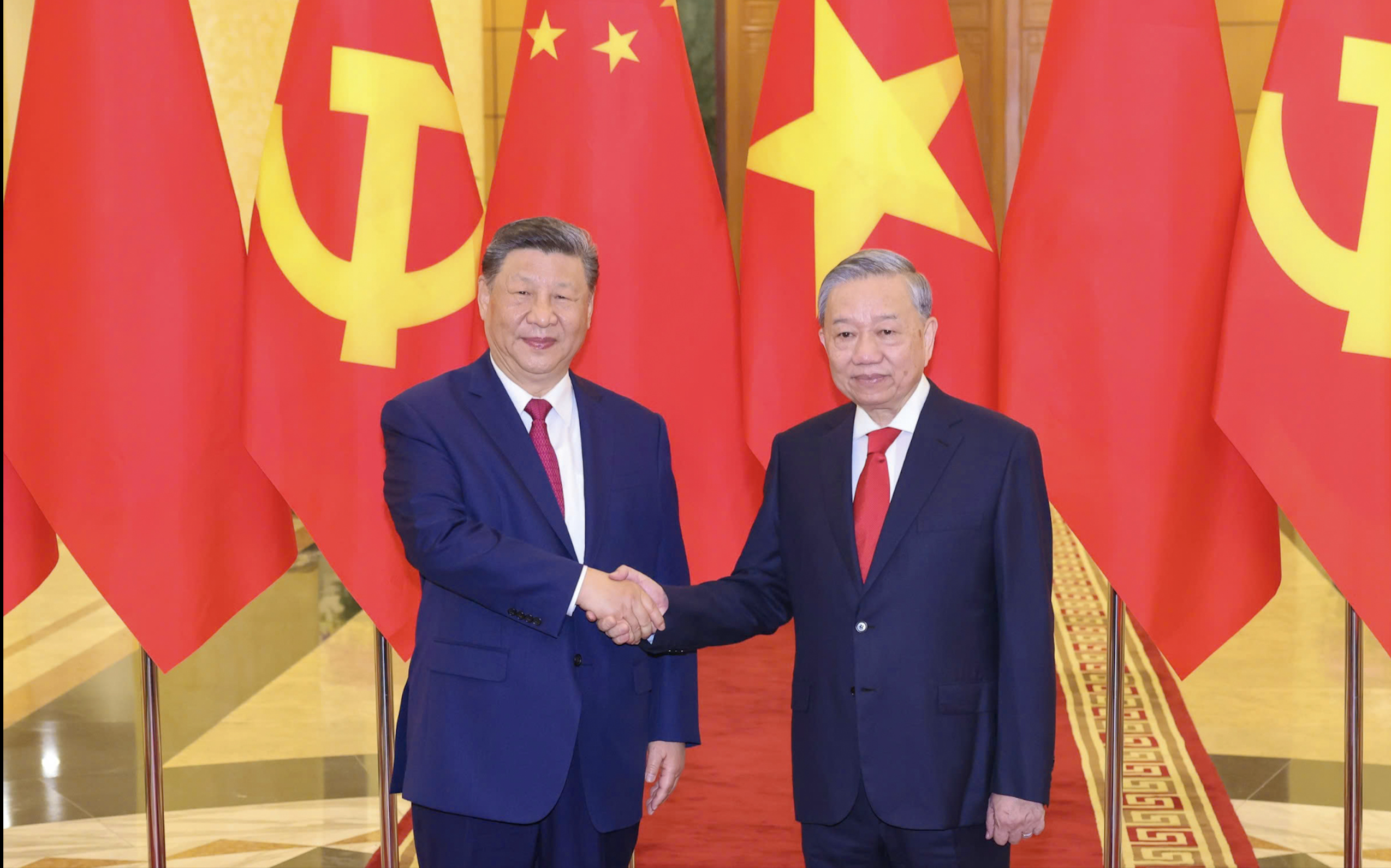

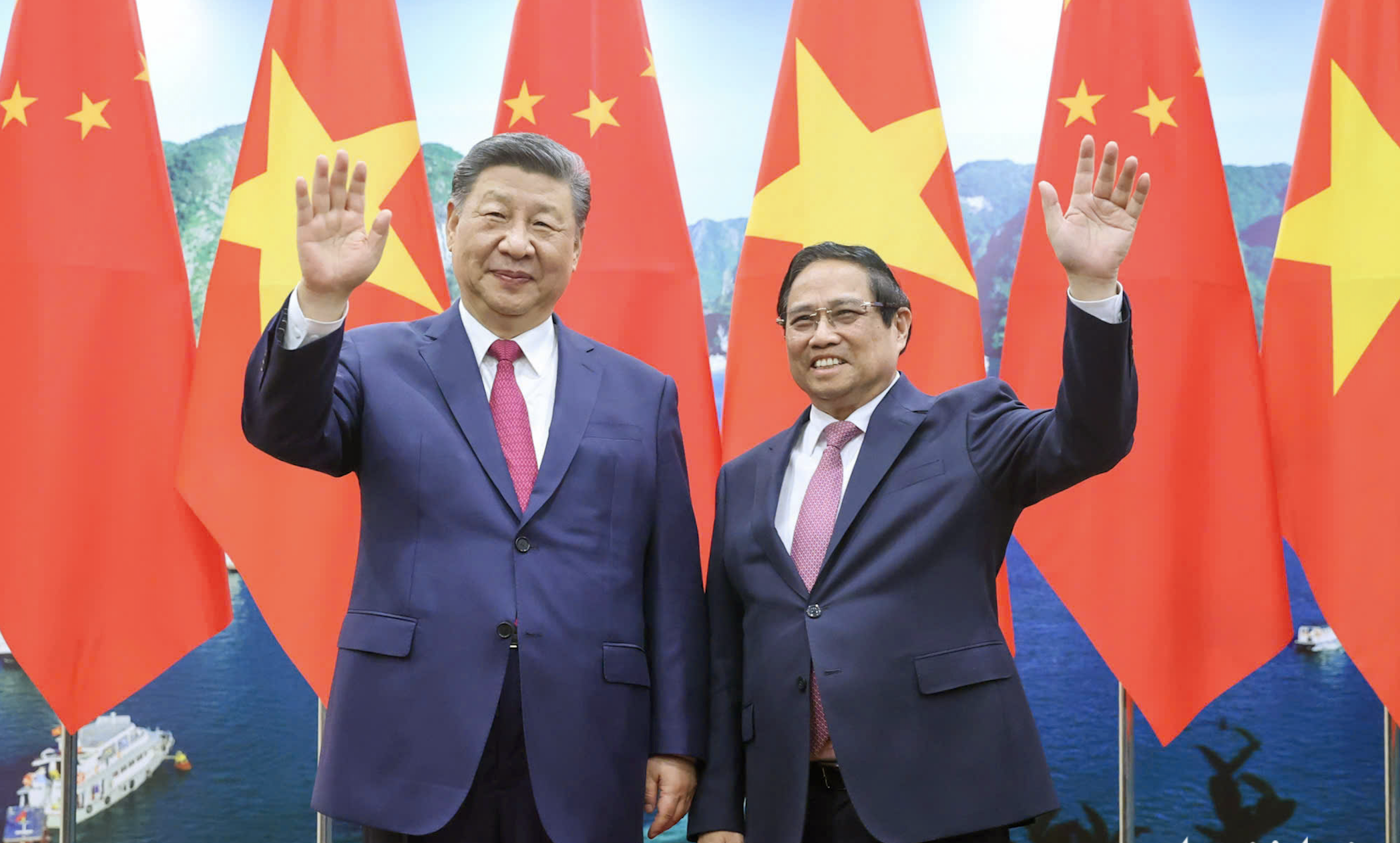

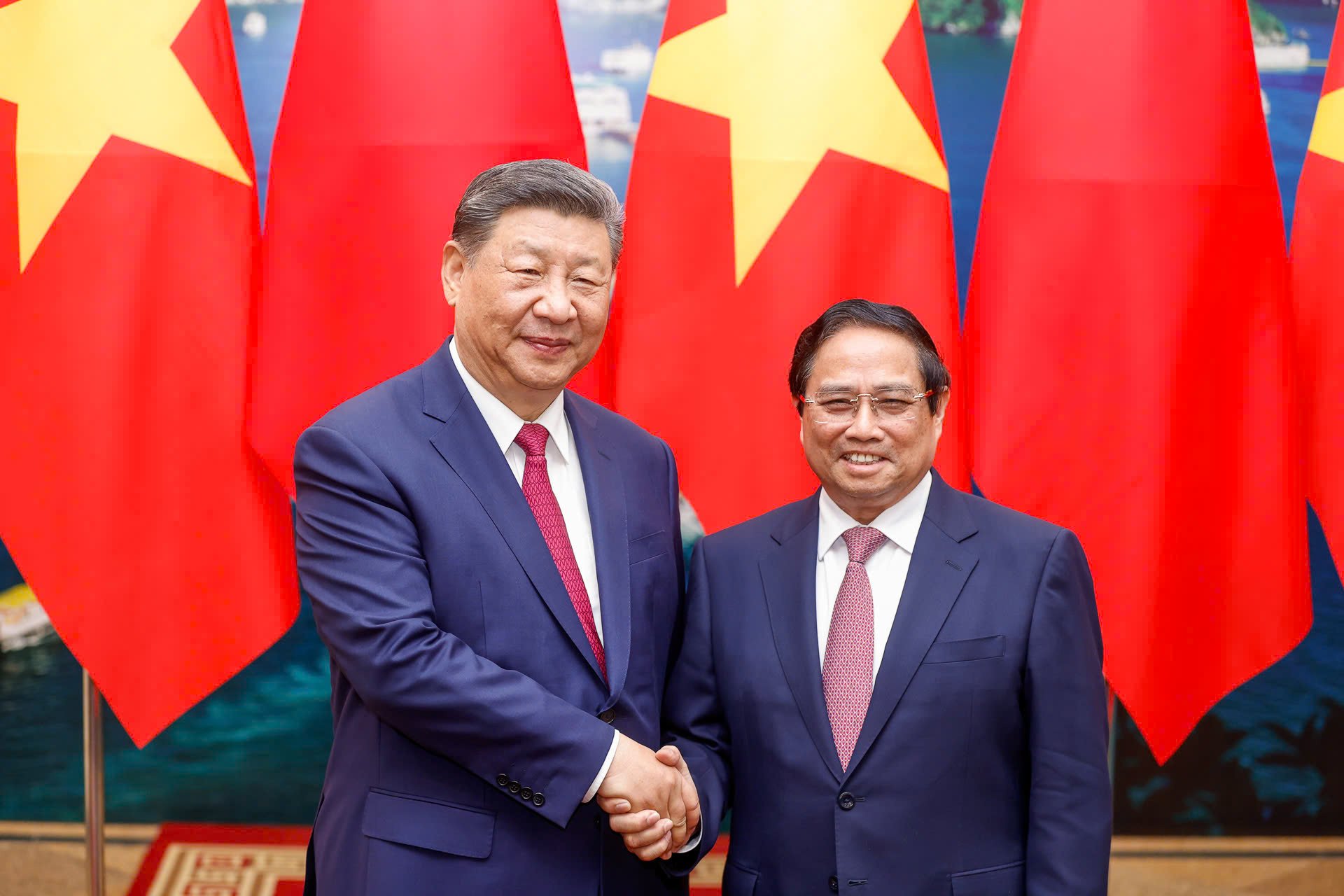

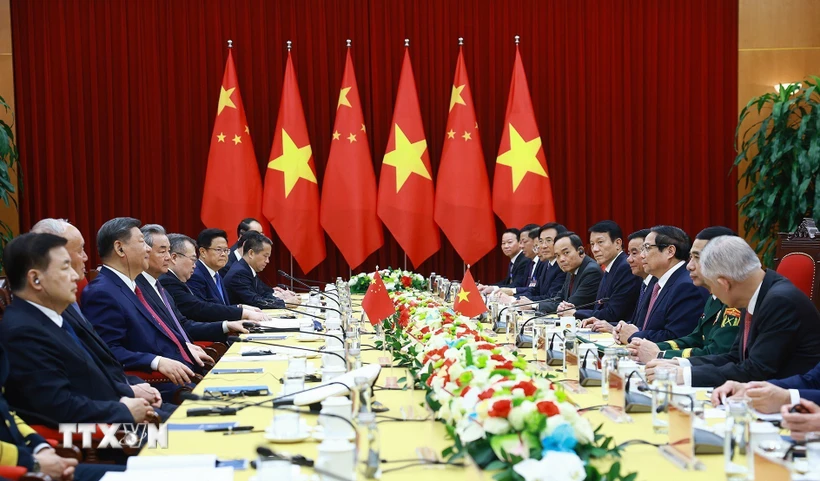

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh meets with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/893f1141468a49e29fb42607a670b174)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man meets with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/4e8fab54da744230b54598eff0070485)

![[Photo] Reception to welcome General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/ef636fe84ae24df48dcc734ac3692867)

Comment (0)