Our sloop sailed upstream for an hour and a half, in a landscape that, in places, seemed to us to be in the Egyptian countryside, somewhere in the far reaches of the delta. On the left, the white sand dunes obscured the sea, and the thunderous crash of the waves could be heard. On the right, the sand was still there, carried by the wind from the sea over the dunes: not piled up, but scattered over the alluvial plain in the form of fine powder, where patches of mica glittered among the pale blue.

In the Marble Mountains caves in the 1920s

Here and there, cultivated areas are divided into wide strips, rice fields stretch out at the foot of dusty hillsides, sand encroachment is prevented by irrigation, barren lands are fertilized, and crops flourish in brackish waters.

Some deep drainage ditches carried water directly from the river, and when the ground was too high for the use of a complex system of canals, wells were dug in sections; a series of bamboo buckets were wound around a crude winch operated by one man. Sometimes the device was operated by a buffalo, whose slow gait and exaggerated silhouette against the vast sky.

On the banks of the fields, groups of workers were busy dredging ditches and building clay banks. They were shirtless and squatting, their heads covered with palm-leaf hats as big as parasols. They no longer looked like people but like giant wildflowers mixed in with the tall grass and gorse bushes.

Occasionally, near the cottage, a woman would appear, lighting a fire or drawing water from a jar. She would replace her bulky hat with a scarf wrapped around her head: from a distance, with her dark, loose-fitting robe revealing her bronzed skin, we would have thought she was a North African woman carrying water, despite her small, thin figure.

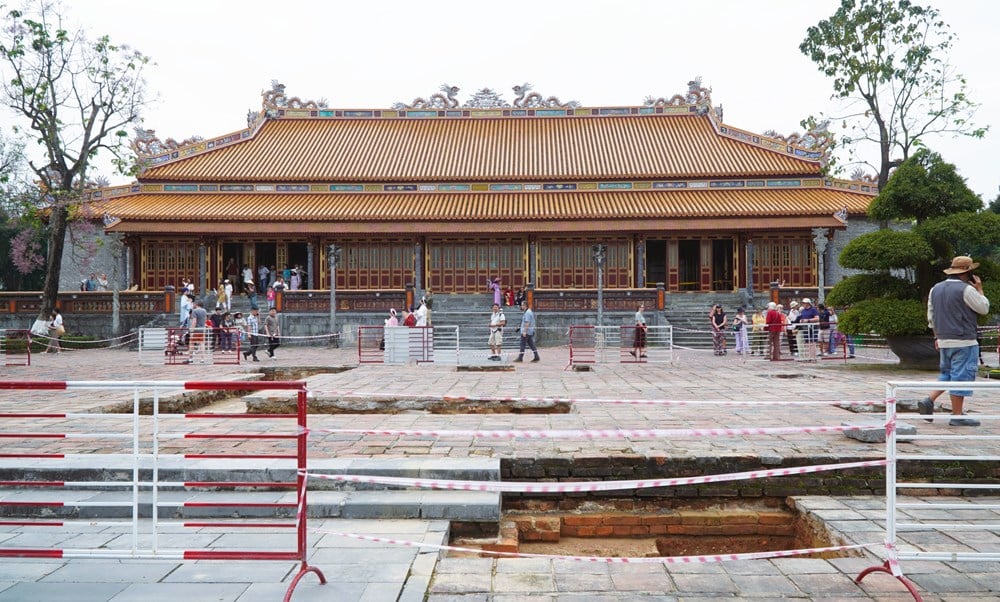

Our boat was deep in a cove, a quarter of a mile from three hills, the highest of which was only 150 metres high. But their isolation and the reflected light made them appear much larger; "mountains" was the word that almost escaped our lips when we saw these marble blocks, with their strange jagged edges, rising between the ocean and the endless, sea-blue plain on the horizon.

For 45 minutes we waded through knee-high dust. There was no vegetation other than a few crisp blades of grass and a bush of linden trees with sparse, grey foliage. Another dune, and then we were at the base of the main mountain with 300 steps carved into the rock, the first 20 of which were buried in sand.

The road up the mountain is not long but very tiring, under the midday sun that burns the western cliffs, igniting a spark at every undulation. But the higher you go, the cooler the sea breeze blows, invigorating and exhilarating you, its moisture accumulates in the smallest cracks, creating conditions for the wallflowers and flowers to bloom in all their shades.

Giant cacti shot up like rockets everywhere. Bushes overlapped each other, roots crawled across, twisted, and threaded through the rocks; branches intertwined and knotted. And soon, above our heads, a canopy of barely perceptible, thread-covered shrubs was a canopy of orchids in full bloom, beautiful and fragile like butterfly wings when a gentle breeze blew, this flower bloomed early and withered in a single day.

The steep path leads to a semicircular terrace: a small pagoda, or rather three rooms with glazed tile roofs and carved Chinese eaves, built in this quiet space by order of Minh Mang, Emperor of Annam, some 60 years ago. These rooms, surrounded by a few small, carefully tended gardens, are no longer used for worship but are the hermitages of six monks - the guardians of this sacred mountain. They live there, in a quiet space, chanting and gardening every day. Occasionally, a few kind-hearted villagers bring them a few baskets of soil to maintain the vegetable garden and some delicious food such as rice and salted fish. In return, these villagers are allowed to worship in the main hall, which is difficult for first-time pilgrims to find without a guide.

This peerless temple was not built by the piety of kings. Nature did the work; no architect's sketch, no poet's dream, could ever equal this masterpiece born of geological change. (to be continued)

(Nguyen Quang Dieu quoted from the book Around Asia: Cochinchina, Central Vietnam , and Bac Ky, translated by Hoang Thi Hang and Bui Thi He, AlphaBooks - National Archives Center I and Dan Tri Publishing House published in July 2024)

Source: https://thanhnien.vn/du-ky-viet-nam-du-ngoan-tai-ngu-hanh-son-185241207201602863.htm

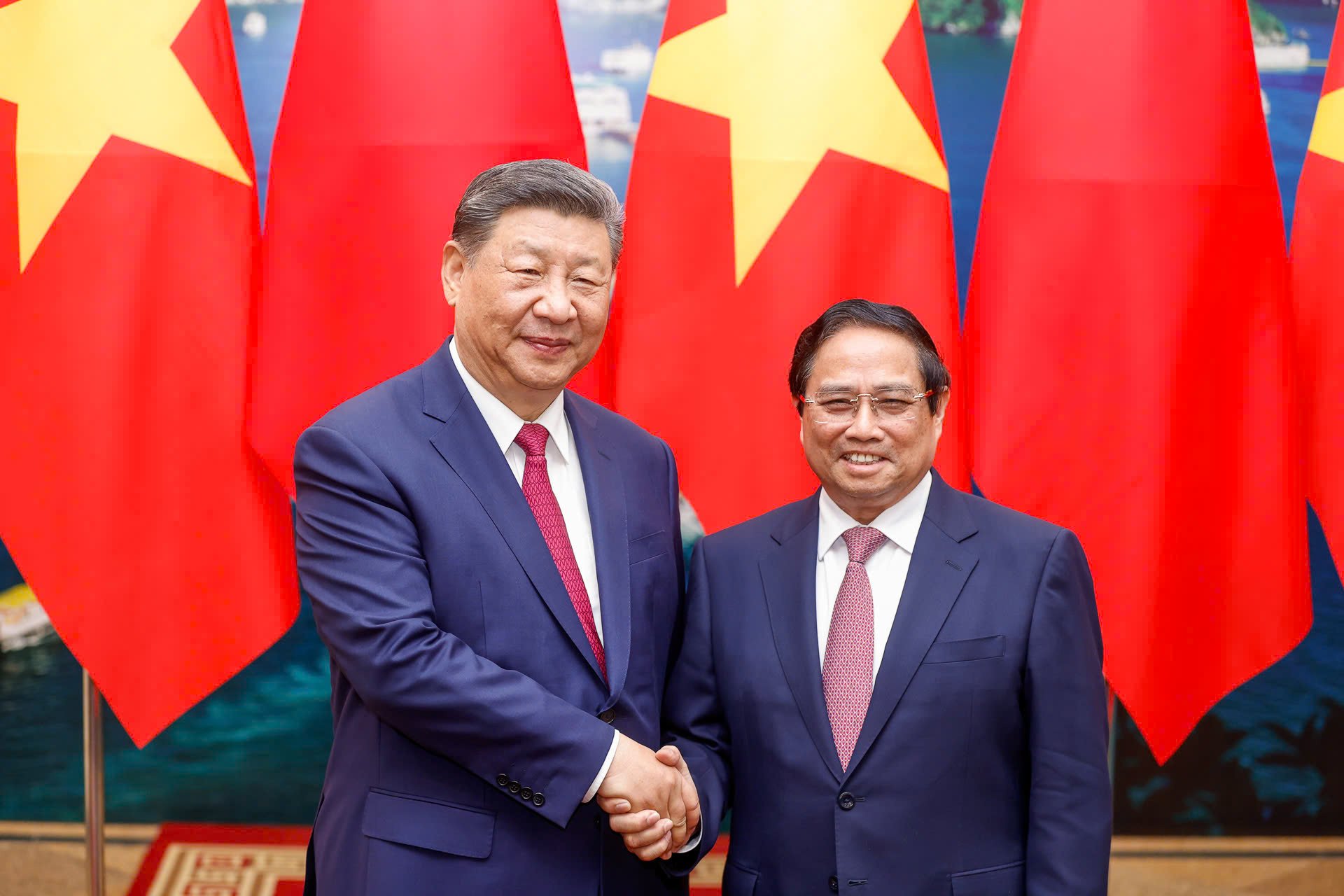

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh meets with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/893f1141468a49e29fb42607a670b174)

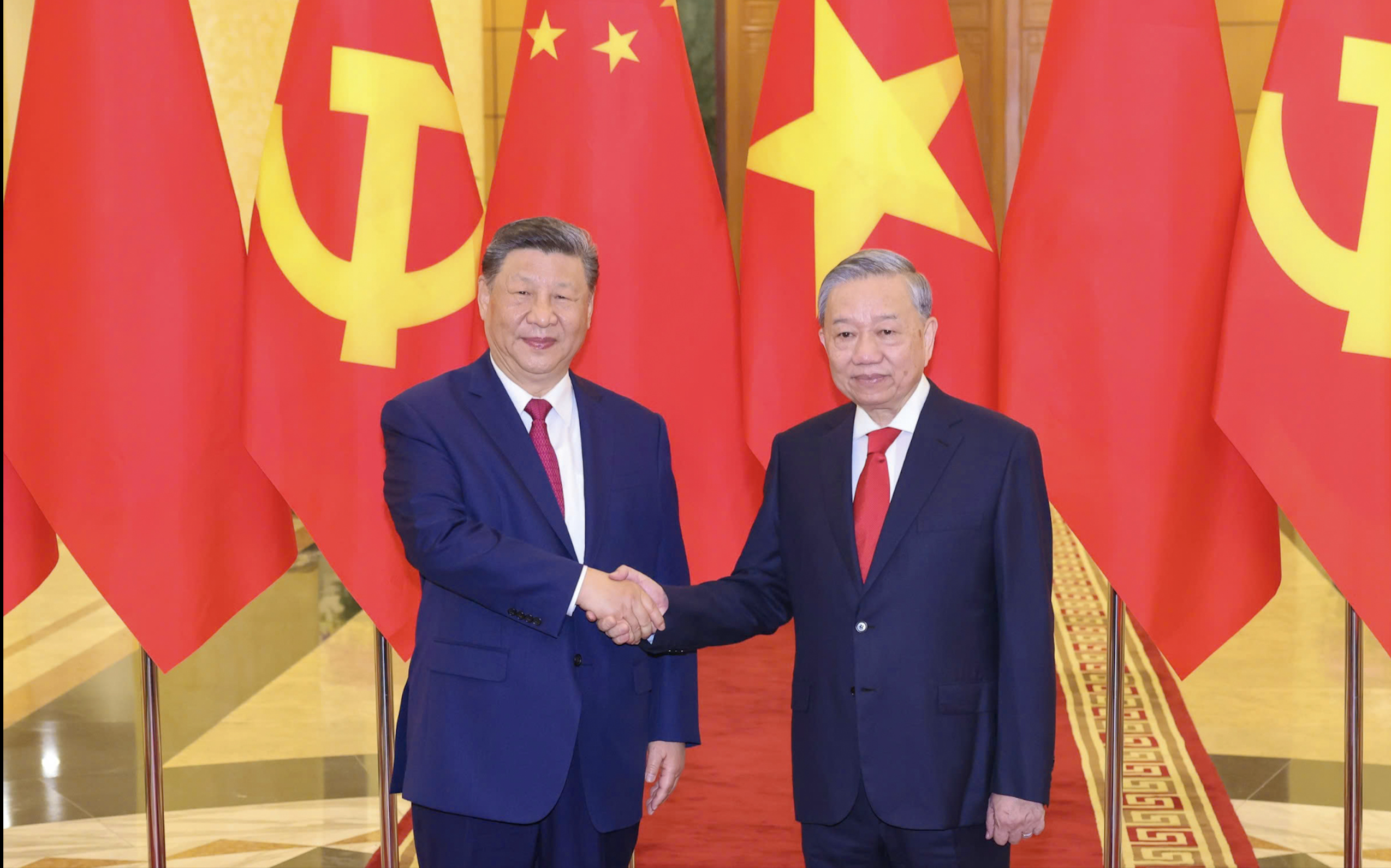

![[Photo] Reception to welcome General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/ef636fe84ae24df48dcc734ac3692867)

![[Photo] Tan Son Nhat Terminal T3 - key project completed ahead of schedule](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/15/85f0ae82199548e5a30d478733f4d783)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man meets with General Secretary and President of China Xi Jinping](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/14/4e8fab54da744230b54598eff0070485)

Comment (0)