YEN BAI This year, over 100 years old, Mr. Sung Sau Cua understands each Shan Tuyet tea tree in Phinh Ho like each of his own children and is determined to preserve them for future generations.

Best friend with Shan Tuyet tea

The gloomy, foggy, and cold weather made the only road running around the mountain from National Highway 32 through the center of Van Chan district to Phinh Ho commune, Tram Tau district (Yen Bai), which has many curves, even more precarious when the view ahead was only 5 meters away, people's faces could not be clearly seen. Following the weak motorbike lights in the thick fog, Mr. Sung Sau Cua's house also appeared before our eyes.

Located at an altitude of more than 1,000m above sea level, Phinh Ho commune is covered in clouds all year round. Photo: Trung Quan.

Located at an altitude of more than 1,000m above sea level, the house has pillars and roof made of sturdy po mu wood, designed low to avoid drafts, which are "sleeping" and suddenly awakened by the appearance of distant guests.

Hearing the sound of the motorbike, Mr. Sau Cua happily ran from behind the house to the front. The sound of the old farmer's solid bare feet on the hard ground, who was over 100 years old this year, made us young people who had just started to cry because of the cold, feel embarrassed and quickly hide our hands that were shaking from the cold.

Unlike the Hmong people I have met who are somewhat shy, reserved, and reserved, Mr. Sau Cua is very excited when strangers come to visit. According to his youngest son, due to his old age, Mr. Sau Cua has not left the commune for a long time, so every time someone from far away comes, he is very happy because he has the opportunity to talk, to share his memories and life lessons that he has spent more than a century summarizing.

Entering the house and sitting next to the blazing wood stove, I had the opportunity to look closely at the man who was at a rare age. The kindness and sincerity emanating from his face, which bore the marks of time, warmed the heart of the person opposite.

Slowly walking into the corner of the house, Mr. Cua gently took a handful of Shan Tuyet tea and put it into a large bowl with his own hands, lifted the pot of steaming boiling water on the stove and quickly filled it. When the tea had steeped, he divided it into small rice bowls, inviting everyone to enjoy. The special way of making and drinking tea made the smoke meet the cold mist and not want to leave, mixed with the fragrant tea aroma, bringing a strangely comfortable and peaceful feeling.

Taking a big sip of tea, Mr. Sau Cua proudly said: “Shan Tuyet Phinh Ho tea is in the high mountains, surrounded by clouds and mist all year round, with a temperate climate, so it grows completely naturally, absorbing the best of heaven and earth, so it has a very unique flavor that cannot be found anywhere else”. Perhaps for someone who has spent his whole life attached to Shan Tuyet tea trees like him, being able to talk about this “soul mate”, “historical witness” is a happiness.

Mr. Cua recalls that since he learned to use a whip to chase buffaloes to graze, he saw Shan Tuyet tea trees growing green all over the hillsides. Realizing that this type of tree had a large trunk, a bark like white mold, was tens of meters high, and had a wide canopy, people kept it to prevent soil erosion. The tea leaves were cool when brewed into water, so households told each other to collect them for daily use, but no one knew its true value.

Mr. Cua's special way of making and drinking tea brings a strange feeling of comfort and peace. Photo: Trung Quan.

When the French occupied Yen Bai, realizing that the seemingly wild tea plants were actually a wonderful drink given by heaven and earth, the French officials directed their secretaries (Vietnamese interpreters) to go into each village to purchase all the dried tea from the people at a price of 1 cent/kg or in exchange for rice and salt.

Peace was restored, but hunger and poverty still surrounded the mountainous region. The Shan Tuyet tea trees witnessed everything, opened their arms, and became a solid support for the people of Phinh Ho to cling to and carry each other through each period of hardship.

At that time, Sau Cua, along with the other young men in the village, went up the mountain early in the morning every day, holding torches and carrying backpacks, picking tea; competing to carry large bundles of firewood to use as fuel for drying tea. When they had finished products, they quickly packed up and crossed the mountains and forests to bring them to Nghia Lo town to sell to the Thai people or exchange them for rice, salt, etc. to bring back. There were no scales, so the tea was packed into small bags according to estimates, and the buyer based on that paid the equivalent amount of rice and salt. Later, it was converted to 5 hao/kg (dried tea).

No matter how difficult it is, I will not sell Shan Tuyet tea trees.

At first thought, newcomers to Phinh Ho thought the Mong people here were lucky, because the Shan Tuyet tea tree grows naturally in the mountains and forests, and they don’t need to be cared for to harvest. It was indeed lucky because not every place was given such privileges, but the journey to exchange tea for rice and salt was not that easy.

Tea trees grow naturally on the mountain, so they are inevitably damaged by pests. The locals lack knowledge and materials to prevent pests. Loving the trees, the villagers only know how to use knives to clear the ground under the tree, gently dig holes to catch each worm. It is unclear whether this method is scientific or not, but each time a worm is removed from the tree, everyone feels a year younger.

Mr. Sung Sau Cua (sitting in the middle) shares his concerns about protecting Shan Tuyet tea trees in Phinh Ho. Photo: Quang Dung.

Not only that, to have quality Shan Tuyet tea buds, people have to climb to the top of the towering trees, meticulously selecting each bud to pick. Over time, everyone realized that if they let the tea trees grow naturally, they would not be able to sprout buds and could "reach the sky" and be unable to harvest. After much thought, people thought of a way to cut off some branches (currently, after 2 crops, people cut the tea trees' branches once).

However, cutting branches also requires technique, if not done properly, the tree will crack, and in cold, humid weather, water will seep into the tree, causing it to wither and die. So, the knives are sharpened and given to the strongest person. The decisive cuts, slanted from the bottom up, are “as sweet as sugar cane” and the tree doesn’t have time to feel like it has just lost its arms.

When harvesting, you must choose the right time for the tea to reach its weight and have the best quality. Normally, people harvest 3 crops a year. The first crop is at the end of March, early April and the last crop is around the end of August, early September of the lunar calendar.

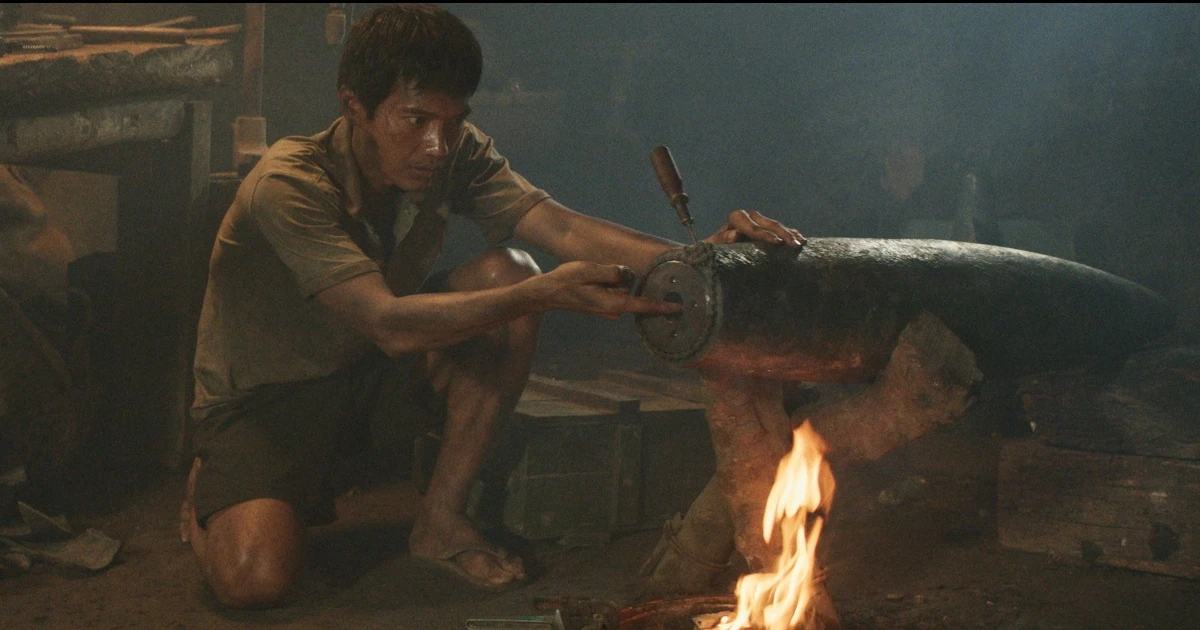

In the past, there were no clocks, so households relied on the sound of roosters crowing to go up the mountain to pick tea. When they heard the gong and the school drum at recess (9-10am), students would return home. Fresh tea brought back, no matter how much or how little, had to be roasted immediately because if left for too long, it would wilt and turn sour. The process of roasting tea had to be extremely calm, ensuring enough time and almost absolute precision. Firewood for roasting tea had to be made from solid wood, do not use po mu wood because the smell of the wood would ruin the aroma of the tea. In addition, avoid letting plastic wrap, packaging, etc. fall into the stove, creating a burnt smell during the roasting process.

Each type of finished tea has a different way of roasting. When bringing home black tea, the fresh leaves must be wilted before being crumpled, left to ferment overnight, and then roasted. White tea only uses young buds covered with white hairs. The processing is not crumpled, but is slow, because if the tea is wilted or dried in conditions that are too hot, it will turn red, and in conditions that are too cold, it will turn black...

According to Mr. Cua, each person has their own secret to roasting tea, but for him, a batch of tea usually takes 3 to 4 hours to roast. Initially, the fire is high, and when the cast iron pan is hot, only the heat from the coal is used. An experience that he still passes on to his children is that when the temperature of the cast iron pan cannot be estimated, it is based on the burning level of the firewood. That is, the firewood is cut into equal sizes, the first time the firewood burns to the point where the tea is added and stirred, and the following times it is done the same way.

“It looks simple, but to feel the right temperature and make a decision to roast tea requires high concentration and intense love for each tea bud. Nowadays, modern machines can set a timer and measure the temperature, but with natural Shan Tuyet tea, absorbing the essence of heaven and earth, roasting with a wood stove is not only a way to preserve the soul of the tea but also a cultural feature in the way of training people,” Mr. Sau Cua confided.

For the people of Phinh Ho, Shan Tuyet tea trees have become family members. Photo: Trung Quan.

When asked what he wishes for most, Mr. Cua said softly: "I hope not to get sick or have pain so that I can protect the ancient Shan Tuyet tea trees with my children and villagers." I am so glad that in the past, whenever I saw a tree with beautiful leaves, people would rush to pick them, "no one cries for the common good". Now that information, trade, and tourism have developed, the value of Shan Tuyet tea is clearer, and every household is actively marking and protecting each tea tree.

The Elderly Association on one hand mobilized the villagers, on the other hand petitioned the local government to agree that no matter how difficult it was, the land and Shan Tuyet tea trees should not be sold to people from other places. The Mong people will hug each tea tree as tightly as the tea roots hug the motherland.

Source

![[Photo] Phuc Tho mulberry season – Sweet fruit from green agriculture](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/10/1710a51d63c84a5a92de1b9b4caaf3e5)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs meeting to discuss tax solutions for Vietnam's import and export goods](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/10/19b9ed81ca2940b79fb8a0b9ccef539a)

![[Photo] Unique folk games at Chuong Village Festival](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/10/cff805a06fdd443b9474c017f98075a4)

![Building the Vietnamese bird's nest brand: [Part 1] Reaching the world](https://vstatic.vietnam.vn/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/4/10/a74ccb6a92a148aa9acd3682fa5ad735)

Comment (0)