According to Jeffrey McGregor, CEO of Truepic, this is just the “scratch of the iceberg” of what could happen in the future: “We’re going to see more AI-generated content floating around social media, and we’re not prepared for it.”

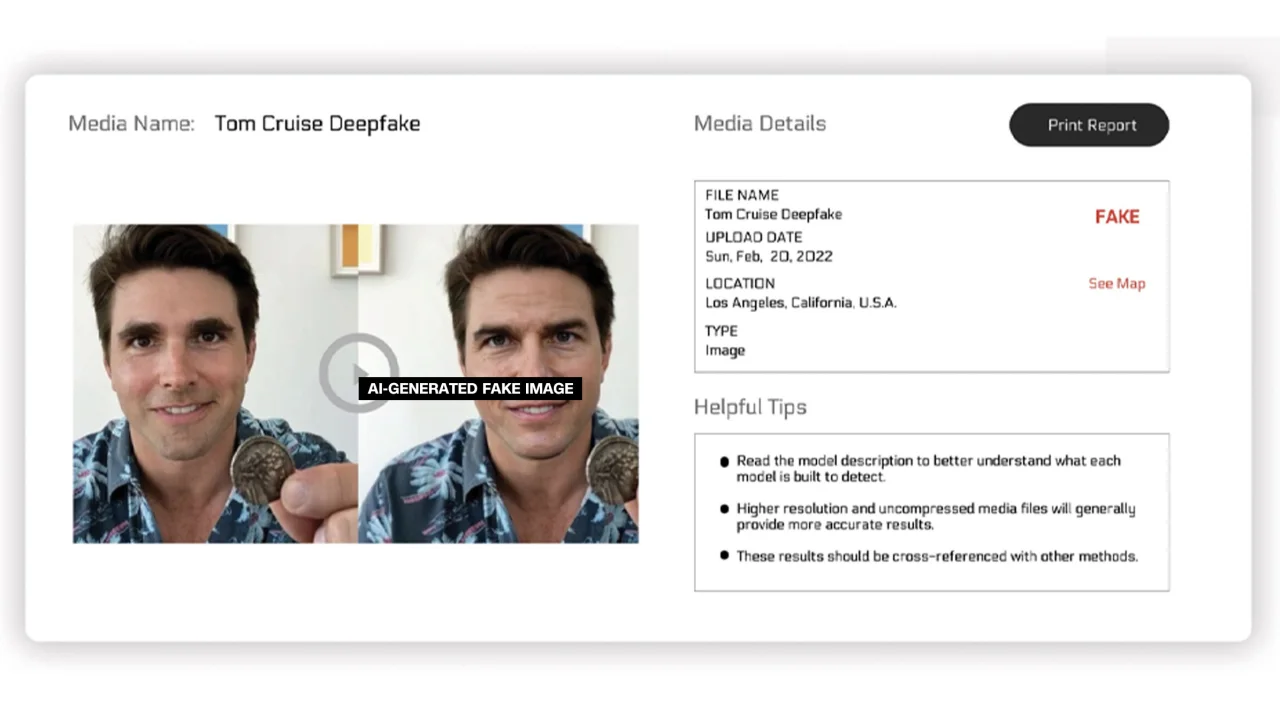

McGregor's company is looking to solve this problem. Truepic offers technology to identify whether an image is real or fake through Truepic Lens. The app collects data including the date, time, location, and device used to create the image, then applies a digital signature to verify it.

Truepic was founded in 2015, a few years before AI-powered photo-generating tools like Dall-E and Midjourney. McGregor said there was a growing need for people and organizations to make decisions based on images, from media companies to insurance companies.

“When anything can be faked, everything can be faked. Generative AI has reached a tipping point in quality and accessibility, we no longer know what is real online,” he commented.

Companies like Truepic have been fighting misinformation for years, but the rise of a new breed of AI tools that can quickly generate images and posts at user prompts has made the effort more urgent. In recent months, fake images of Pope Francis wearing a fur coat and former US President Donald Trump being arrested have been widely shared online.

Some lawmakers are calling on tech companies to address the problem. Vera Jourova, vice-president of the European Commission, urged signatories to the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation — a list that includes Google, Meta, Microsoft and TikTok — to “put in place AI content recognition technology and clearly label it for users.”

A growing number of startups and Big Tech are trying to implement standards and solutions to help people determine whether an image or video is AI-generated. But as AI technology advances faster than humans can keep up, it’s unclear whether these technical solutions will fully solve the problem. Even OpenAI, the company behind Dall-E and ChatGPT, admitted earlier this year that its own efforts to help detect AI-generated text were “not perfect” and warned against taking everything on faith.

Arms race

There are two approaches to the problem: One relies on developing programs that identify AI-generated images after they are produced and shared online; the other focuses on marking images as real or AI-generated in the first place with some kind of digital signature.

Reality Defender and Hive Moderation are taking the first approach. Their platform allows users to upload a photo to be scanned and receive a report on the percentage of real or fake photos. Reality Defender says it uses “proprietary deepfake and generative content fingerprinting technology” to detect AI-generated videos, audio, and images.

This could be a lucrative business if the problem becomes a constant concern for individuals and businesses. These services are free to try and then charge a fee. Hive Moderation charges $1.50 per 1,000 images, plus an “annual contract” (with discounts). Reality Defender’s pricing varies based on a number of factors.

Ben Colman, CEO of Reality Defender, says the risks are multiplying every month. Anyone can create fake images using AI without a computer science degree, without renting a server, without knowing how to write malware, all they need is a Google search. Kevin Guo, CEO of Hive Moderation, calls it an “arms race.” They have to figure out all the new ways people are creating fake content, understand it, and put it into a data set for classification. While the percentage of AI-generated content is low right now, that will change in just a few years.

Defensive approach

In a defensive approach, larger tech companies are looking to incorporate some sort of watermark into images to authenticate them as real or fake as soon as they are created. The effort is largely led by the Content Provenance and Authentication Alliance (C2PA).

C2PA was founded in 2021 to create a technical standard for certifying the origin and history of digital content. It combines the efforts of the Adobe-led Content Authentication Initiative (CAI) and Project Origin, backed by Microsoft and the BBC, which focuses on combating misinformation in digital news. Other companies involved in C2PA include Truepic, Intel, and Sony.

Based on C2PA guidelines, CAI created an open-source tool for companies to create metadata containing information about images. It helps creators share details about how they created their images in a transparent way. This way, end users can see what has been changed and decide for themselves whether the image is authentic.

“Adobe is not making money from this effort. We do it because we think it needs to exist,” Andy Parsons, senior director at CAI, told CNN. “We think it’s a very important foundational defense against misinformation.”

Does the tech industry want to pause AI development because of concerns for humanity?

Does the tech industry want to pause AI development because of concerns for humanity?Many companies have already integrated the C2PA standard and CAI tools into their applications. For example, Adobe recently added its AI image creation tool Firefly to Photoshop. Microsoft also announced that AI creations created by Bing Image Creator and Microsoft Designer will be cryptographically signed in the coming months.

Others, like Google, appear to be pursuing a hybrid approach. In May, Google announced the About this image tool, which tells users when a photo was indexed on Google. Additionally, every image generated by Google’s AI will be marked in the original file to provide context if the image is found on another platform or website.

While tech companies are trying to address concerns around AI-generated imagery and the integrity of digital media, experts in the field stress that they need to work together and with governments to address the issue. Beyond calling on platforms to take the issue seriously and stop promoting fake content, regulation and education are needed.

This isn’t something any single company, government, or individual can do alone, Parsons says. We need everyone to participate. At the same time, though, tech companies are pushing to get more AI tools out into the world.

(According to CNN)

Source

Comment (0)