With interest rates high, savings falling and political instability, expecting the world economy to continue to grow is "taking a huge gamble", according to the Economist.

Even as geopolitical tensions simmer in some parts of the world, the global economy is still buoyant. Just a year ago, everyone thought that high interest rates would soon lead to a recession. Now even optimists are puzzled that this has not happened. Instead, the US economy boomed in the third quarter. Around the world, inflation is falling, unemployment remains largely low, and major central banks are signaling a pause in interest rate hikes.

However, the Economist argues that the joy cannot last. The foundations for growth today appear shaky, with many threats ahead.

First, the strength of the economy has led many to believe that, while interest rates will not rise as quickly, they will not fall much. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) kept rates unchanged this past week. The Bank of England (BoE) followed suit.

Long-term bond yields have surged as a result. The US government now pays 5% for 30-year bonds, up from just 1.2% during the pandemic. Even economies known for their low interest rates have changed. Germany’s borrowing costs were negative not long ago, but now its 10-year bond yields are close to 3%. The Bank of Japan has barely kept its 10-year bond yield at 1%.

Some, including US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, argue that higher interest rates are a good thing, reflecting the strength of the global economy. But The Economist disagrees, calling them dangerous because sustained high interest rates could cause current economic policies to fail and growth to falter.

A trader on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on September 13, 2022. Photo: Reuters

To see why today’s favorable conditions can’t continue, consider why the U.S. economy has been doing better than expected. People have been using the money they’ve saved during the pandemic, and it’s expected to run out soon. Recent data show that households have $1 trillion left, the smallest amount of savings capacity since 2010.

As savings dwindle, high interest rates begin to bite, forcing consumers to spend less. In Europe and America, bankruptcies are rising, even among companies that issue long-term bonds to get low interest rates.

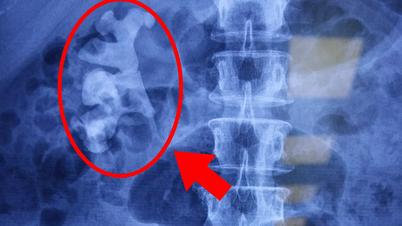

Home prices will fall — especially when adjusted for inflation — as mortgage rates get higher. Banks holding long-term securities — backed by short-term loans, including from the Fed — will have to raise capital or merge to plug the hole in their balance sheets caused by higher interest rates.

Second, excessive fiscal spending has helped countries recover and grow rapidly in recent years, but it looks unsustainable if interest rates remain high. According to the IMF, Britain, France, Italy and Japan are all likely to run budget deficits of around 5% of GDP by 2023.

In the 12 months to September, the US budget deficit was $2 trillion, or 7.5% of GDP. In a climate of low unemployment, such borrowing is less prudent. Public debt in rich countries as a share of GDP is the highest since the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

When interest rates were low, sky-high debt was manageable. Now that interest rates have risen, public debt is draining the budget. So high interest rates over a long period of time risk putting governments at odds with their central banks. In the US, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has stressed that he will never cut interest rates to ease the pressure on government budgets.

Regardless of what Mr Powell says, persistently high interest rates will make investors question the government’s commitment to low inflation and its ability to repay its debt. The European Central Bank’s debt is already starting to look unbalanced. Even when Japanese government bond yields were as low as 0.8% last year, 8% of the budget was still going to interest payments.

If pressure builds, some governments will tighten their belts, causing economic pain. It is possible that a prolonged period of high interest rates will end in itself by causing economic weakness, forcing central banks to cut interest rates without causing a sharp rise in inflation.

A brighter scenario is that productivity growth soars, perhaps thanks to innovative artificial intelligence (AI). The resulting increase in revenue and profits helps companies accept higher margins. AI’s potential to boost productivity may help explain why the U.S. stock market has been doing so well so far. Behind it is the continued growth in market capitalizations of the seven tech giants. Otherwise, the S&P 500 would probably be down this year.

But the opposite is true of a world beset by threats to productivity growth. Donald Trump has vowed to impose new tariffs if he returns to the White House. Governments are increasingly distorting markets with deglobalizing industrial policies.

Add to that the growing burden on budgets as populations age, the green energy transition and conflicts around the world demand more public spending. Given all this, the Economist argues that anyone betting that the world economy can continue to grow is taking a big gamble.

Phien An ( according to The Economist )

Source link

![[Photo] Ho Chi Minh City: Many people release flower lanterns to celebrate Buddha's Birthday](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/10/5d57dc648c0f46ffa3b22a3e6e3eac3e)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam meets with Chairman of the Federation Council, Parliament of the Russian Federation](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/10/2c37f1980bdc48c4a04ca24b5f544b33)

Comment (0)