|

| Analysts say that just one piece of bad news can cause oil and gas prices to skyrocket. Pictured: Oil tanks at Hungary's Duna Refinery, which receives Russian crude via the Druzhba pipeline. (Source: AFP) |

Don't blame weak demand

In the period after Russia launched a special military operation in Ukraine (February 2022), any bad news caused energy prices to skyrocket.

Last year, when news broke that a fire had forced a US gas plant to shut down, strikes had clogged French oil terminals, Russia had asked Europe to pay for fuel in rubles, or the weather seemed worse than usual, the market immediately became excited.

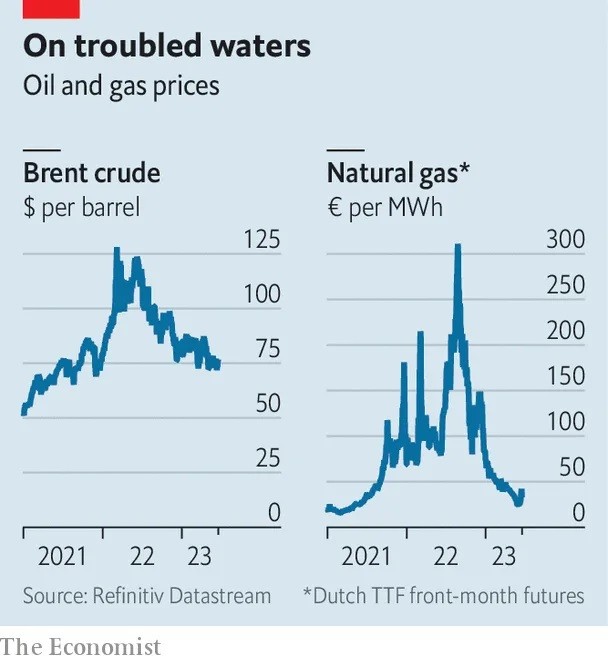

But things have changed since January 2023. Brent crude oil is hovering around $75 a barrel, down from $120 a year ago. In Europe, gas prices are at 35 euros (about $38) per megawatt hour (mwh), 88% lower than their peak in August 2022.

|

| Oil and gas price chart from 2021-2023, (Source: The Economist) |

In that context, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its partners (OPEC+) announced production cuts to raise oil prices.

Meanwhile, in the US, the number of active oil and gas rigs has fallen for seven straight weeks. Several Norwegian gas facilities – vital to Europe – are shutting down for extended maintenance. The Netherlands has also shut down Europe’s largest gas field.

Yet despite these moves, energy prices remain low, and any price increases are short-lived. So what is keeping oil and gas prices so low?

Lower-than-expected consumer demand may be part of the answer.

Global economic growth expectations have been slashed in recent months, with the collapse of several banks this spring raising fears of a looming recession in the United States.

Meanwhile, inflation is battering consumers in Europe, and in both places the full impact of rising interest rates has yet to be felt.

In China, the recovery from the pandemic is proving much weaker than expected. Weak growth is reducing fuel demand.

But a closer look reveals that the weak demand story is not entirely convincing. Despite the disappointing recovery, China consumed a record 16 million barrels of crude oil per day in April. The recovery in trucking, tourism and travel after the lifting of Zero Covid policies means more diesel, gasoline and jet fuel are being used.

In the U.S., gasoline prices are down 30 percent from a year ago, a good sign for the summer, which is the peak travel season. In Asia and Europe, high temperatures are expected to persist, increasing demand for gas-fired power generation to keep cool.

Supply is constantly increasing

A more convincing explanation can be found on the supply side of the equation. High prices over the past two years have encouraged increased production in non-OPEC countries.

Oil is flowing into global markets from the Atlantic region, through a combination of wells (in Brazil and Guyana) and shale and oil sands production (in the US, Argentina and Canada). Norway is also pumping more oil.

JPMorgan Chase bank estimates that non-OPEC production will increase by 2.2 million barrels per day by 2023.

In theory, this is balanced by the production cuts announced in April by core OPEC members (1.2 million bpd) and Russia (500,000 bpd), while Saudi Arabia added 1 million bpd this June.

But in reality, production in these countries has not fallen as much as promised, while other OPEC countries are increasing exports. Venezuela has increased sales thanks to investment from Chevron, an American energy giant. Iran is exporting at its highest level since 2018, when the US imposed new sanctions on the Islamic country.

According to statistics, 1/5 of the world's oil today comes from countries under Western sanctions, sold at a discount and thus causing prices to fall.

On the gas front, the supply situation is more complicated. Russia’s Nord Stream pipeline that pumps supplies to Europe remains shut. However, Freeport LNG, a facility that handles a fifth of U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and was damaged by an explosion last year, is back in operation.

Other Russian exports to continental Europe continue. Norwegian gas flows will resume completely in mid-July.

Most importantly, Europe’s existing storage facilities are nearly full, with a 73% occupancy rate compared with 53% a year ago and on track to reach the 90% target by December. Wealthy Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea also have plenty of gas.

As inflation soared and interest rates remained modest, investors flocked to commodities seen as attractive hedges against rising prices, such as crude oil. Now, as speculators expect inflation to ease, the appeal of crude has diminished.

Higher interest rates also increase the opportunity cost of holding crude, so physical traders are selling their stocks. The amount of oil in global floating storage fell from 80 million barrels in January to 65 million barrels in April, the lowest since early 2020.

Oil prices could also rise later this year. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that global oil demand will hit a record 102.3 million barrels per day in 2023. Oil supply will also hit a record.

According to some banks, the market will fall into deficit in the second half of this year. As winter approaches, competition for LNG between Asia and Europe will intensify. Winter freight rates are expected to rise.

However, the “nightmare” of last year’s energy crisis is unlikely to repeat itself. Many analysts expect Brent crude to stay close to $80 a barrel and not reach triple digits.

Gas futures markets in Asia and Europe point to a 30% increase from current levels by the fall, rather than anything more extreme. Energy markets have adapted over the past 12 months. Even so, it only takes one bad news story to send oil and gas prices soaring.

Source

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man meets with Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/15/e71160b1572a457395f2816d84a18b45)

![[Photo] Prime Ministers of Vietnam and Thailand visit the Exhibition of traditional handicraft products](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/15/6cfcd1c23b3e4a238b7fcf93c91a65dd)

Comment (0)