Japan marked 13 years on Monday (March 11) since a massive earthquake and tsunami struck the country's northern coast, killing nearly 20,000 people, wiping out entire towns and destroying the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, sparking deep fears about radiation that persist to this day.

People observe a minute of silence at 2:46 p.m. - the time of the earthquake in Iwaki, Fukushima, on March 11. Photo: Kyodo News

What happened 13 years ago?

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck Japan, triggering a tsunami that devastated northern coastal towns in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures.

A tsunami as high as 15 meters in some areas hit the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, destroying power supply and fuel cooling systems and flooding reactors 1, 2 and 3. The accident caused a large radioactive leak and contamination in the area.

Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) said the tsunami was unforeseeable, but investigations said the accident was due to human error, specifically safety negligence and lax oversight by regulators.

Since then, Japan has introduced stricter safety standards and at one point moved to phase out nuclear power. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida's government has reversed that policy and accelerated the restart of viable reactors to maintain nuclear power as Japan's main source of electricity.

Mr. Kishida attended a memorial service in Fukushima on March 11. The whole country observed a minute of silence at 2:46 p.m. - the time of the devastating earthquake 13 years ago.

What happens to the people in the area?

About 20,000 of the more than 160,000 evacuated residents across Fukushima have yet to return home, although some areas have reopened after decontamination.

In Futaba, the hardest-hit town and home to the Fukushima Daiichi plant, a small area was opened in 2022. About 100 people, or 1.5% of the pre-disaster population, have returned.

Barriers are erected to restrict access to the area near the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Futuba. Photo: Kyodo News

Along with Futaba, Okuma town sacrificed part of its land to build a temporary storage facility for nuclear waste collected from the decontamination process. Okuma town saw 6% of its former residents return.

Annual surveys show that the majority of evacuees do not intend to return home, citing lack of jobs, loss of public facilities and schools, as well as concerns about radiation.

Towns hit by the disaster, including those in Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, have seen their populations plummet. Fukushima Governor Masao Uchibori said he hopes more people will return to Fukushima to open businesses or help with reconstruction.

Water pollution treatment and seafood concerns

Fukushima Daiichi began releasing treated water into the ocean in August 2023 and is currently releasing its fourth batch of treated water, weighing 7,800 tons. So far, daily seawater sampling results have met safety standards.

The plan has faced opposition from local fishermen and neighboring countries, especially China, which has banned imports of Japanese seafood.

Fukushima Daiichi has struggled since 2011 to deal with contaminated water. Contaminated cooling water is pumped up, treated and stored in about 1,000 tanks. The government and TEPCO say the water is diluted with large amounts of seawater before being released, making it safer than international standards.

Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant on August 24, 2023, shortly after operator TEPCO began releasing the first batch of treated reactor water into the Pacific Ocean. Photo: Kyodo News

Despite concerns that the discharge will damage the fishing industry, Fukushima's reputation for seafood still holds a special place in the eyes of the Japanese people.

China's ban on Japanese seafood, which mainly affects scallop exporters in Hokkaido, appears to have prompted Japanese consumers to eat more Fukushima seafood.

Fishing in Fukushima returned to normal in 2021, but local catches are now just a fifth of pre-disaster levels due to a decline in the number of fishermen and smaller catches.

Sampling and monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency have also boosted confidence in local fish. Japan has earmarked 10 billion yen ($680 million) to support fisheries in Fukushima.

Is there any progress in removing melted radioactive fuel?

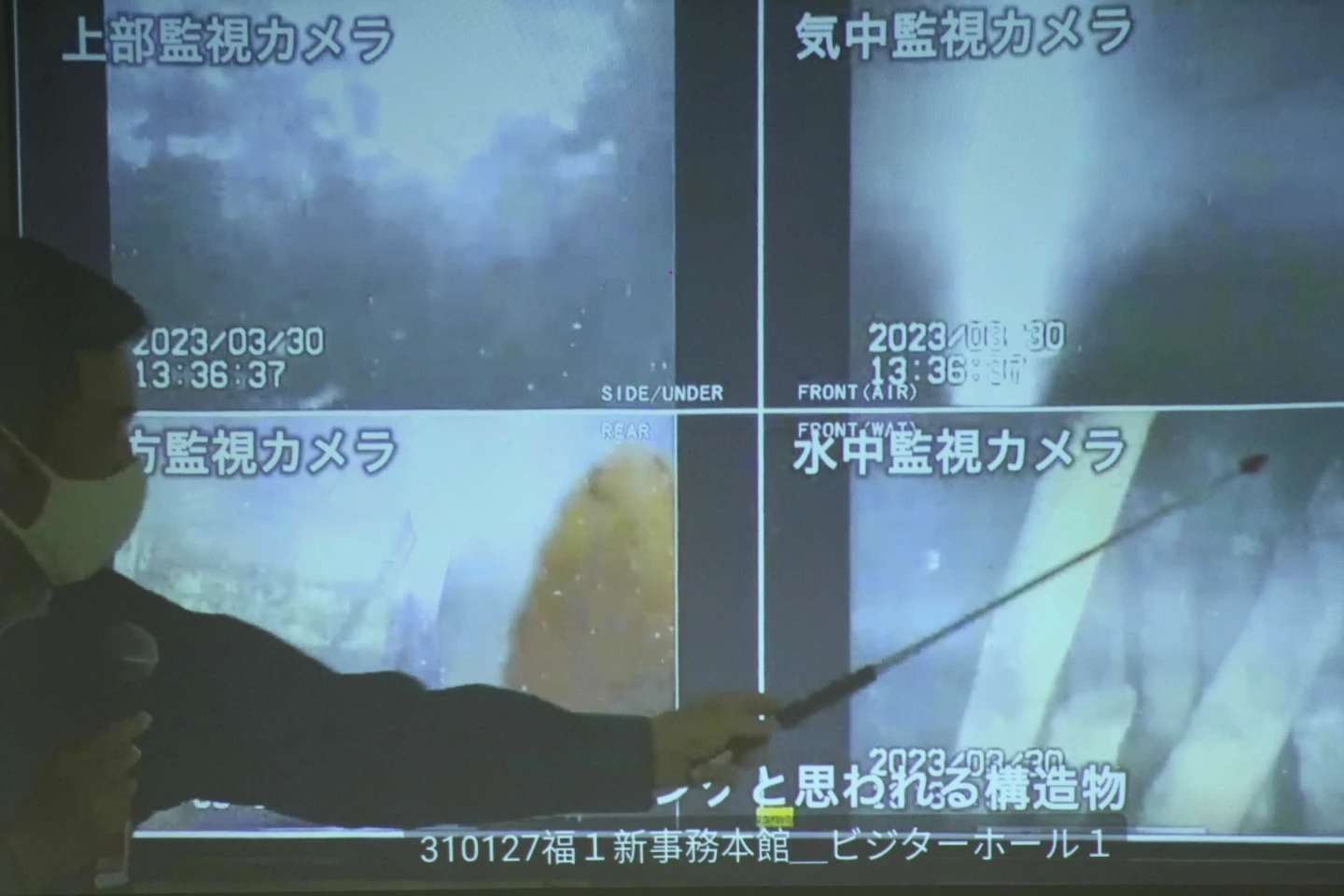

The inside of the three reactors remains largely a mystery. Little is known about the state of the melted radioactive fuel or its exact location within the reactors. Robotic probes have gotten a glimpse inside the three reactors, but the investigation has been hampered by technical failures, high radiation levels and other problems.

About 880 tons of melted nuclear fuel remain inside the three damaged reactors. Japanese officials say removing it will take 30 to 40 years.

It is important to have data on the melted fuel so that plans can be made to safely dispose of it. TEPCO aims to take the first samples by the end of this year from the least damaged reactor No. 2.

TEPCO representatives show photos taken by a robotic probe inside one of the three reactors. Photo: AP

TEPCO has been trying to retrieve samples by sending a robotic arm through the rubble and hopes by October they can use a simpler device that looks like a fishing rod.

Most of the fuel in the worst-hit reactor No. 1 has fallen from the core to the bottom of its main containment vessel. Some has penetrated and mixed with the concrete floor, making removal extremely difficult.

Hoai Phuong (according to AP)

Source

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs conference on anti-smuggling, trade fraud, and counterfeit goods](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/14/6cd67667e99e4248b7d4f587fd21e37c)

Comment (0)