From an unsuccessful businessman, John Lethbridge became rich with the invention of a diving suit that allowed him to dive to a depth of about 20 m.

Replica of John Lethbridge's diving suit in the Cité de la Mer museum, Cherbourg, France. Photo: Ji-Elle

The Cité de la Mer museum in Cherbourg, France, hangs a strange object that looks like some kind of medieval torture device, but is actually a replica of the world's first closed diving suit. The suit's inventor, John Lethbridge (1675 - 1759), was a wool merchant in the town of Newton Abbot, Devon, England. Little is known about his childhood or what inspired him to create the diving suit. According to the BBC , he had 17 children, so he struggled to make ends meet.

Before Lethbridge's invention, diving was done with the help of a "diving bell" - a device that resembled an upside-down cup or bell without a pendulum, which was lowered into the water so that the person inside could breathe the air trapped in the bell. The diver could climb out from the bottom to open it, do his job, and then climb back into the bell.

In 1715, John Lethbridge became the first person to design a functional, airtight diving suit, which he called a “diving machine.” The suit resembled a wooden barrel about six feet long, inside which the diver lay face down. The device had a circular window for observation and two holes through which the arms could be extended. Two oiled leather tubes wrapped around the upper arms created a nearly waterproof seal.

The suit has no air supply other than the air trapped inside before sealing. While that may not sound like much, it is enough to keep Lethbridge submerged for about 30 minutes at a time. The suit has two air valves at the top. Fresh air can be pumped in through tubes connected to the valves when the diver surfaces. The suit is raised and lowered by cables, but Lethbridge also provides weights that the diver can discard and surface unaided.

Lethbridge hoped his device would go to great depths. But when he tested it, he found that the water pressure at depths beyond 15 metres caused leaks around the arms, windows and entrances. He found that he could still easily go down to 18 metres. The maximum depth was 22 metres, but the descent would be difficult.

Despite its limitations, Lethbridge used the suit to great effect in British waters and elsewhere in the Atlantic to salvage valuable cargo from shipwrecks. Many London shipping companies soon took notice of Lethbridge and hired him for salvage work.

In 1794, while en route from the Netherlands to Java, the Dutch East India Company ship Slotter Hooge was wrecked by strong winds near Porto Santo, Madeira. Of the 254 men on board, only 33 survived. The ship sank in about 60 feet of water, carrying 3 tons of silver ingots and three large chests of coins. Lethbridge was hired for £10 a month, plus expenses and bonuses. On his first attempt, Lethbridge recovered 349 silver ingots, more than 9,000 coins, and two guns. He made several dives to the wreck throughout the summer and recovered nearly half of the treasure.

Over the next 30 years, Lethbridge worked on many wrecks and made a fortune. From an unsuccessful wool merchant struggling to feed his family, Lethbridge became a wealthy man, owning the Odicknoll estate in Kingskerswell.

Lethbridge's original diving suit no longer exists, but the drawings do. Several replicas have been made and are on display in maritime museums around the world, including one in his hometown of Newton Abbot.

Thu Thao (According to Amusing Planet )

Source link

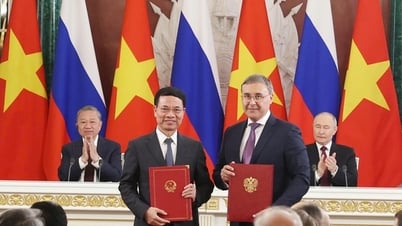

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam meets and expresses gratitude to Vietnam's Belarusian friends](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/c515ee2054c54a87aa8a7cb520f2fa6e)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam arrives in Minsk, begins state visit to Belarus](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/76602f587468437f8b5b7104495f444d)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam concludes visit to Russia, departs for Belarus](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/0acf1081a95e4b1d9886c67fdafd95ed)

![[Video] Bringing environmental technology from the lab to life](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/57d930abeb6d4bfb93659e2cb6e22caf)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man attends the Party Congress of the Committee for Culture and Social Affairs](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/f5ed02beb9404bca998a08b34ef255a6)

Comment (0)