The fear that large, long-standing corporations might fail because of slow innovation does not occur in the US, but the opposite, according to the Economist.

Attend any business conference or open any management book and you’re likely to come across a similar message: the pace of change in business is accelerating and no one is safe.

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI) have left many giant corporations anxiously awaiting the attack of the new names, like Goliath worried about the prospect of David like Kodak and Blockbuster - two giants collapsed by the digital revolution.

"The Innovator's Dilemma" - a 1997 book by management expert Clayton Christensen - observes that companies that occupy the top positions are often hesitant to pursue radical innovations that make their products or services cheaper or more convenient for fear of losing profits.

As technology advances rapidly, that creates opportunities for newcomers who are not constrained by such considerations. But in the Internet age, big American businesses have been less vulnerable. The old giants have become more resilient, not weaker.

From Walmart to Wells Fargo, the Fortune 500 list of America's largest companies by revenue accounts for about 20% of jobs, half of revenue and two-thirds of profits. The Economist looked at the age of each company, taking into account mergers and spin-offs.

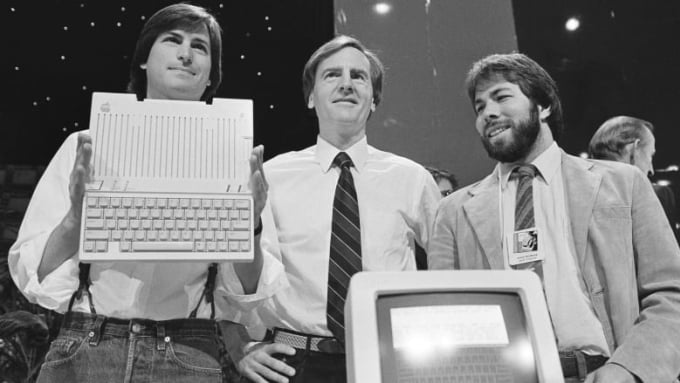

From left, the three founders of Apple, Steve Jobs, John Sculley and Steve Wozniak, photographed in 1984. Apple is considered a middle-aged giant because it was founded in 1976. Photo: AP

As a result, only 52 of the 500 companies were founded after 1990, the year that marked the beginning of the Internet era. They include Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta, but not Apple and Microsoft, two middle-aged tech giants. Only 7 of the 500 were founded after Apple launched the first iPhone in 2007.

By comparison, 280 companies were founded before the United States entered World War II. In fact, the rate at which new large companies are created is slowing. In 1990, 66 of the Fortune 500 companies were 30 years old or younger. Since then, the average age has risen from 75 to 90.

Julian Birkinshaw, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at London Business School, explains that the digital revolution has not been so revolutionary in some areas of the economy . Industries such as media, entertainment and shopping have been radically transformed. But the same has not been true of extracting oil from the ground or transmitting electricity.

High-profile failures like WeWork, a much-hyped office-sharing company that is on the verge of collapse, or Katerra, which tried and failed to redefine the construction industry using prefabricated structures, have discouraged even those with ambitions to disrupt those traditional industries.

Another reason is that legacy platforms have given leaders time to adapt to digital technologies . For example, 65% of Americans bank online, but nearly all of the banks they use are older. The average age of Fortune 500 banks, including JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, is 138.

Fewer than 10% of Americans switched banks last year, according to consulting firm Kearney. That makes it difficult for new financial players to build scale. The same is true of the U.S. insurance industry, which is dominated by legacy giants like AIG and MetLife.

This model is not unique to financial services. Walmart, America’s most powerful retailer, missed the rise of e-commerce. David Glass, the company’s president in the 1990s, predicted that online sales would never exceed those of its largest supermarket.

A shopper leaves a Walmart store in Bradford, Pennsylvania, U.S., July 20, 2020. Photo: Reuters

But Walmart’s financial muscle and massive customer base have given it the ability to change course later. Only Amazon now sells more online than it in the US. The recent growth of electric vehicles by Ford and General Motors, the two largest US automakers, is another example. Its vast resources have allowed it to spend heavily on restructuring its business at a time when it is increasingly difficult for startups to raise capital.

A third explanation for the longevity of America's established giants is that their wealth advantage creates its own incentives for innovation. The economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the phrase "creative destruction" in his 1911 book "The Theory of Economic Development." He argued that economic progress is driven largely by new entrants to the market.

However, by his 1942 work "Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy," he had changed his mind. In fact, it was big companies—even monopolies—that drove innovation, thanks to their ability to pour money into research and development (R&D) and quickly monetize breakthroughs by using existing customers and operations. So progress was driven by the constant fear of being overthrown by the big guys.

The US tech giants provide a stark illustration. Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta and Microsoft invested a combined $200 billion in R&D last year, equivalent to 80% of their total profits and 30% of all R&D spending by publicly traded US companies.

Or John Deere — America's largest agricultural equipment company founded in 1837 — has been at the forefront of innovations like driverless tractors and smart sprayers that use machine learning to detect and target weeds.

John Deere's ambition is to make farming fully automated by 2030. After poaching laid-off techies from Silicon Valley, it now employs more software engineers than mechanical engineers.

Giants and newcomers also often play complementary roles in innovation. Economist William Baumol wrote in 2002 about the “David-Goliath symbiosis” in which fundamental breakthroughs are created by independent innovators and then reinforced by established companies.

A 2020 study by Annette Becker of the Technical University of Munich and her co-authors divided R&D spending by a sample of companies into exploratory research and commercially oriented development. They found that the share of research declined as the company grew larger.

Similarly, 2018 work by Ufuk Akcigit (University of Chicago) and William Kerr (Harvard Business School) found that patents by large corporations are less bold and more focused on improving existing products and processes.

That division may help explain why many startups are acquired by established companies. John Deere’s purchase of Blue River in 2017, for example, gave the company the technology behind its smart lawn sprayer, which it could then sell through its vast network of distributors.

The final explanation has to do with demographics. Young companies are often founded by young people, says John Van Reenen of the London School of Economics. But between 1980 and 2020, the share of the U.S. population aged 20 to 35 fell from 26% to 20%. As a result, the rate of new business formation fell from 12% to 8% over the same period.

In a 2019 study comparing differences in population growth and business formation across US states, Fatih Karahan of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concluded that the decline in population growth accounts for 60% of the decline in new business formation over the past 40 years.

New business registrations in the US rose in late 2020 after plunging in the early months of the pandemic. Now, new business growth is higher than before Covid-19. The business boom has been largely concentrated in hotels and retail, which were hit hard by Covid. Optimists hope that a recent wave of investment in AI startups can sustain the growth. Even if that happens, the giant corporations that have long dominated are likely to remain.

Phien An ( according to The Economist )

Source link

![[Photo] Vietnamese shipbuilding with the aspiration to reach out to the ocean](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/20/24ecf0ba837b4c2a8b73853b45e40aa7)

![[Photo] Panorama of the Opening Ceremony of the 43rd Nhan Dan Newspaper National Table Tennis Championship](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/19/5e22950340b941309280448198bcf1d9)

![[Photo] Close-up of Tang Long Bridge, Thu Duc City after repairing rutting](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/19/086736d9d11f43198f5bd8d78df9bd41)

![[VIDEO] - Enhancing the value of Quang Nam OCOP products through trade connections](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/17/5be5b5fff1f14914986fad159097a677)

Comment (0)