In the 14th century, an alchemist made an amazing discovery . Mixing nitric acid with ammonium chloride (then called sal ammoniac) produced a fuming, highly corrosive solution that could dissolve gold, platinum, and other precious metals. This solution was called aqua regia or “royal water.”

This is considered a major breakthrough in the journey to discover the Philosopher's Stone - a mythical substance that people believe can create the elixir of life and convert base metals such as lead into gold.

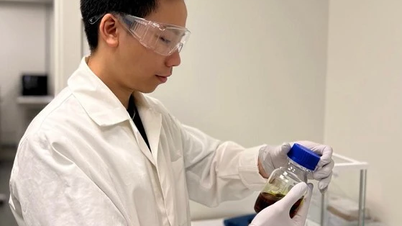

Freshly prepared aqua regia. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Although the alchemists ultimately failed in this task, aqua regia (now produced by mixing nitric acid and hydrochloric acid) is still used to etch metals, clean traces of metals and organic compounds from laboratory glassware, and is also used in the Wohlwill Process to refine gold to 99.999% purity.

In a bizarre twist from World War II, the corrosive liquid was used in an even more dramatic case, helping a chemist save his colleague's scientific legacy from the Nazis.

In the late 1930s, Nazi Germany was in dire need of gold for its upcoming war of aggression. To achieve this goal, the Nazis banned the movement of gold out of the country, and with the ongoing persecution of Jews, German soldiers confiscated large amounts of gold and other valuables from Jewish families and other persecuted groups.

Among the confiscated items were Nobel Prize medals won by German scientists, many of whom had been dismissed in 1933 because of their Jewish ancestry.

A Nobel gold medal. (Photo: AFP)

After journalist and pacifist Carl von Ossietzky was imprisoned and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935, the Nazis banned all Germans from receiving or holding any Nobel Prizes.

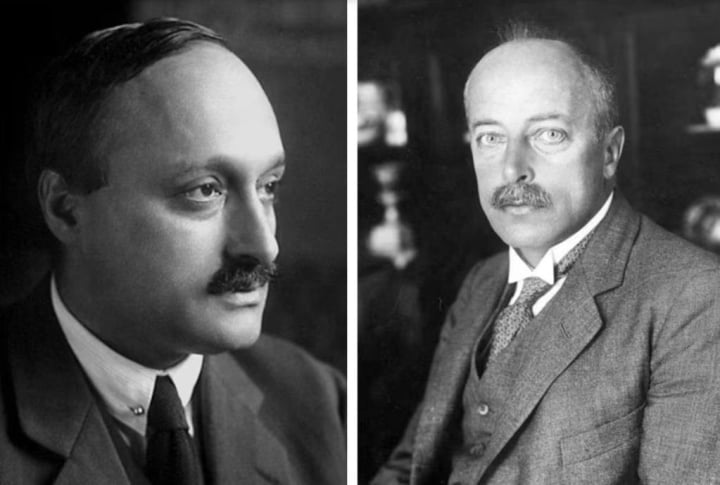

Among the German scientists affected by the ban were Max von Laue and James Franck. Von Laue received the 1914 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on X-ray diffraction in crystals, while Franck and his colleague Gustav Hertz received the prize in 1925 for confirming the quantum nature of electrons.

In December 1933, von Laue, who was Jewish, was expelled from his position as a consultant at the Federal Institute of Physics and Technology in Braunschweig under the newly enacted Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service. Franck, although exempt from this law due to his previous military service, resigned from the University of Göttingen in protest in April 1933.

Together with fellow physicist Otto Hahn, who won the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of nuclear fission, von Laue and Franck helped dozens of persecuted colleagues emigrate from Germany during the 1930s and 1940s.

Not wanting the Nazis to confiscate their Nobel medals, von Laue and Franck sent them to Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who had won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922, for safekeeping. The Institute of Physics that Bohr founded in Copenhagen had long been a safe haven for refugees fleeing Nazi persecution. It worked closely with the Rockefeller Foundation in the United States to find temporary jobs for German scientists. But on April 9, 1940, everything changed when Adolf Hitler invaded Denmark.

As the German army marched through Copenhagen and closed in on the Institute of Physics, Bohr and his colleagues faced a dilemma. If the Nazis discovered Franck and von Laue’s Nobel medals, the two scientists would be arrested and executed. Unfortunately, the medals were not easy to hide, as they were heavier and larger than today’s Nobel medals. The names of the winners were also prominently engraved on the back, making the medals little more than solid gold death warrants for Franck and von Laue.

In desperation, Bohr turned to George de Hevesy, a Hungarian chemist who worked in his laboratory. In 1922, de Hevesy had discovered the element hafnium and had later pioneered the use of radioactive isotopes as tracers to track biological processes in plants and animals—work for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1943. At first, de Hevesy suggested burying the medals, but Bohr immediately rejected the idea, knowing that the Germans would surely dig up the grounds of the Institute of Physics in search of the medals. So de Hevesy came up with a solution: dissolve the medals in aqua regia.

Aqua regia can dissolve gold by combining nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, whereas either chemical alone cannot. Nitric acid can usually oxidize gold, producing gold ions, but the solution quickly becomes saturated, stopping the reaction.

When hydrochloric acid is added to nitric acid, the resulting reaction produces nitrosyl chloride and chlorine gas, both of which are volatile and escape from the solution as vapor. The more of these products escape, the less effective the mixture becomes, meaning that aqua regia must be prepared immediately before use. When gold is immersed in this mixture, the nitrosyl chloride will oxidize the gold.

However, the chloride ions in the hydrochloric acid will react with the gold ions, producing chloroauric acid. This removes the gold from the solution, preventing the solution from becoming saturated and allowing the reaction to continue.

Max von Laue and James Franck - two scientists whose Nobel gold medals were dissolved to deceive the Nazis. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

But while this method worked, it was a slow process, meaning that once de Hevesy had dipped the medals into a glass beaker of aqua regia, he was forced to wait for hours for them to dissolve. Meanwhile, the Germans were getting closer than ever.

However, eventually the gold medals disappeared, and the solution in the beaker turned pink and then dark orange.

The job done, de Hevesy then placed the beaker on a laboratory shelf, hiding it among dozens of other brightly colored chemical beakers. Amazingly, the ruse worked. Although the Germans searched the Institute of Physics from top to bottom, they never suspected the beaker containing the orange liquid on de Hevesy’s shelf. They believed it was just another innocuous chemical solution.

George de Hevesy, himself Jewish, remained in Nazi-occupied Copenhagen until 1943, but was eventually forced to flee to Stockholm. Upon arriving in Sweden, he was informed that he had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. With the help of Hans von Euler-Chelpin, a Swedish Nobel laureate, de Hevesy found a position at Stockholm University, where he remained until 1961.

When he later returned to his Copenhagen laboratory, de Hevesy found the vial of aqua regia containing the dissolved Nobel medals exactly where he had left them, intact on the shelf. Using ferric chloride, de Hevesy precipitated the gold from the solution and gave it to the Nobel Foundation in Sweden, which used the gold to recast the Franck and von Laue medals. The medals were returned to their original owners in a ceremony at the University of Chicago on January 31, 1952.

Although dissolving the gold medal was a small matter, George de Hevesy's clever act was one of countless acts of resistance to the Nazis that helped ensure the ultimate victory of the Allies and the collapse of fascism in Europe.

Although aqua regia is often thought of as the only chemical that can dissolve gold, this is not entirely accurate, as there is another element involved: the liquid metal mercury. When mixed with almost all metals, mercury penetrates and mixes with their crystal structure, forming a solid or paste-like substance called an amalgam.

This process is also used in the mining and refining of silver and gold from ores. In this process, crushed ore is mixed with liquid mercury, causing the gold or silver inside the ore to leach out and mix with the mercury. The mercury is then heated to evaporate, leaving behind the pure metal.

(Source: Tin Tuc Newspaper/todayifoundout)

Useful

Emotion

Creative

Unique

Source

![[Photo] Prime Ministers of Vietnam and Thailand visit the Exhibition of traditional handicraft products](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/15/6cfcd1c23b3e4a238b7fcf93c91a65dd)

Comment (0)