Once a dominant force in the chip industry, Intel was gradually overtaken by rivals Nvidia and AMD, forcing CEO Pat Gelsinger to take a gamble that could cost him his entire career.

Gelsinger understood very well that he had to act quickly to prevent Intel from becoming the next American tech giant to be left behind by its rivals. Over the past decade, Nvidia has overtaken Intel to become the world's most valuable semiconductor manufacturer. Competitors are constantly launching the most advanced chips. Intel's market share is also being eroded by its long-time rival, AMD.

Intel has recently been repeatedly delayed in launching new chips and has faced anger from customers. "If things had gone well, we wouldn't be in this mess. Intel has many serious problems to solve, from leadership and personnel to methodology," he said when he took office as CEO in 2021.

Gelsinger found that Intel's problems stemmed primarily from a shift in its chip manufacturing operations. Intel was renowned for its ability to both design integrated circuits and manufacture chips in its own factories. However, chip manufacturers now focus on only one of these two things. Intel, meanwhile, has yet to make significant progress in manufacturing chips designed by other companies.

To date, reversing the situation remains very difficult. Gelsinger's plan was to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in new factories, manufacturing for other companies in addition to producing Intel's own products. But two years have passed, and this contract manufacturing continues to face numerous problems.

According to WSJ sources, mobile chip giant Qualcomm and electric vehicle manufacturer Tesla explored the possibility of Intel manufacturing chips for them, but later abandoned the idea. Tesla argued that Intel could not provide the same robust chip design services as other outsourcing companies. Qualcomm withdrew after discovering several technical flaws in Intel's chips.

"Chip manufacturing is a service industry. Intel doesn't have that culture yet," Gelsinger said in an interview.

Pat Gelsinger during a Senate hearing in March 2022. Photo: Bloomberg

Whether he succeeds or not will affect not only Intel's fate, but also that of other companies. TSMC (Taiwan) and Samsung Electronics (South Korea) are currently the world's most advanced chip manufacturers. Chinese companies are also catching up. The US is also striving to strengthen its domestic chip industry, due to escalating US-China tensions and Covid-19 disrupting supply chains from Asia.

Intel became a Silicon Valley giant in the 1980s and 90s thanks to its microprocessors (CPUs) used in personal computers. Under CEO Andy Grove, Intel's chips supported Microsoft's Windows operating system. IBM also used Intel products in its widely used home and office computers.

In the 2000s, Intel attempted and failed to break into the mobile phone and high-end computer graphics chip manufacturing market. In recent years, TSMC and Samsung have surpassed Intel in producing chips with the smallest transistors and the fastest processing speeds.

The global chip market is projected to exceed $1 trillion by the end of this decade. Therefore, becoming the world's leading contract chip manufacturer "is not an option," but a necessity, Gelsinger said.

Gelsinger grew up on a small farm in Pennsylvania, enjoyed repairing TVs and radios, and attended a technical school near his home. At 18, he moved to California to work for Intel and rose to become the company's first Chief Technology Officer in 2001. He was later fired for a failed computer graphics chip project. Gelsinger then moved to the software company VMware, where he served as CEO for eight years.

He returned to Intel in February 2021, knowing that turning things around wouldn't be easy. His plan was to significantly expand Intel's factories and create a chip manufacturing division to increase orders. Before taking office as CEO, he spoke with Intel's board members about this plan, and they all supported it.

He returned to Intel at a time when there was a global chip shortage due to the boom in personal computer sales during the pandemic. Industry profits suddenly surged, but then declined as the pandemic subsided and people returned to work, leading to another chip market surplus. This complicated Gelsinger's plans.

On April 27, Intel announced its heaviest quarterly loss in history, and projected further losses for the following quarter. They cut dividends, launched a cost-cutting campaign (including mass layoffs), and reduced executive salaries. Intel aims to reduce costs by $10 billion annually until 2025.

They are also installing millions of dollars worth of chip manufacturing equipment in new factories to meet chip demand. Plans for a $200 million research center in Israel have been canceled. A $700 million Oregon lab project has also been halted. Air shuttle services for employees between manufacturing centers in Oregon and Arizona and headquarters in Silicon Valley are also on hold.

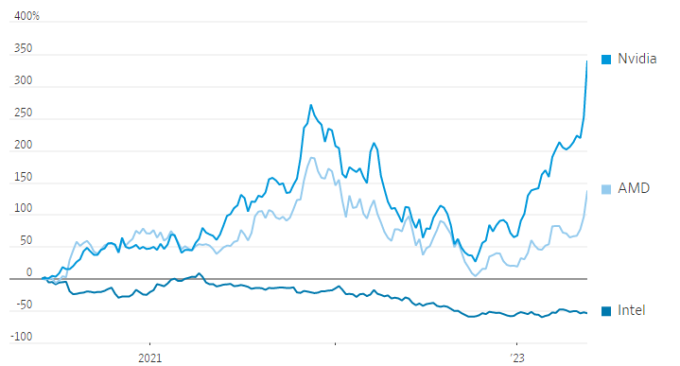

Intel's stock has fallen 30% since Gelsinger was announced as CEO. Meanwhile, the PHLX Semiconductor index, which tracks the semiconductor industry, has risen 10%. TSMC's market capitalization is now four times that of Intel. Nvidia's value is even eight times higher. On May 30th, Nvidia's market capitalization reached $1 trillion.

Stock price movements of Intel, AMD, and Nvidia over the past three years. Chart: WSJ

Gelsinger said he was confident Intel could fulfill its commitment to achieving five advances in chip technology within four years. They also expect to produce the world's most advanced microprocessors within the next few years.

"There are many challenges and risks involved in implementation. It will take them a long time to execute that multi-year strategy," said Andrew Boyd, Chief Investment Officer at Gibraltar Capital Management. His firm sold all of its shares in Intel in January, after 15 years of considering it a core asset.

Gelsinger is optimistic that Intel could become one of the world's two largest contract chip manufacturers. "Can TSMC continue to grow until the end of this decade? The answer is yes. What about Samsung? Yes, too. And Intel? I expect we will grow much faster than both of those companies," he said.

Intel's leaders also aim to be number two by 2030, behind TSMC. They estimate that by attracting just a few major customers, Intel's revenue could increase by an additional $20-25 billion per year until the end of this decade.

Before each board meeting, Gelsinger would invite them to dinner and ask for their support. "Are we still on the same page? Are we still on the right track? Is the strategy still working? This is a tough road, and once we've started, we need to stick together," he would tell them.

Intel chairman Frank Yeary affirmed their continued support for Gelsinger and stated that "the company is making progress." However, they still have a lot of work to do.

To accelerate its contract chip manufacturing operations, Intel agreed last year to acquire Tower Semiconductor, an Israeli contract manufacturer, for nearly $6 billion. However, the deal is facing legal troubles and is unlikely to be completed anytime soon.

Qualcomm – a company specializing in chip design and outsourcing – also wants to work with Intel. They have sent a team of engineers to study the production of mobile phone chips at Intel's factories. Qualcomm is impressed with a manufacturing technology that Intel expects to be the most advanced in the world by the end of next year.

Early last year, Intel sent representatives to Qualcomm's headquarters to meet with CEO Cristiano Amon. However, in June, Intel missed a crucial milestone toward commercial production of this chip. In December 2022, they fell further behind schedule with another deadline.

Qualcomm executives therefore believed Intel would have difficulty producing the type of mobile phone chips they wanted. They announced a temporary suspension of the collaboration pending progress from Intel, according to WSJ sources.

This source explains that Intel has so far focused only on chips for personal computers. Therefore, making chips for phones, with their limited battery life, requires new skills and designs. Intel recently announced it is collaborating with Arm – a chip design company specializing in making microchips for phones.

In late 2021, Tesla also began considering having Intel manufacture the data and image processing chips for its self-driving capabilities. Tesla has long used Samsung products and recently began collaborating with TSMC. Tesla designs the chips, but needs other companies to manufacture them. This is something Intel is not yet able to do.

Intel's top customer is currently chipmaker MediaTek. Intel supplies MediaTek's less advanced chips for smart TVs and Wi-Fi transceiver modules. They also make chips for computer hard drive manufacturer Seagate.

Last year, Intel only recorded $895 million in revenue from its chip manufacturing segment, accounting for less than 2% of total revenue. In meetings last year, Gelsinger told chip manufacturing employees that he was betting his entire career on the manufacturing business and would do everything to achieve it.

The US government is also looking to revive this activity, after shifting much of the production to Asia – where labor costs are lower and officials offer more generous incentives. Last year, Washington activated the Chips Act, providing $53 billion in funding for domestic chip manufacturing. US President Joe Biden later visited an Intel factory in Ohio.

Gelsinger's plan is based on the assumption that demand for chips will rebound strongly. When announcing the company's earnings results at the end of April, he predicted that demand would recover from the end of this year.

While acknowledging that some Intel factories are under construction without having secured any customers yet, Gelsinger said this is a gamble he is willing to take.

"If you don't have a bit of a daring streak, you shouldn't even get into the semiconductor industry," he said.

Ha Thu (according to Wall Street Journal)

Source link

![[Image] Lunar New Year 2026 is celebrated with great fanfare around the world.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/17/1771339826059_155b0e14cbf624b0045-2993-jpg.webp)

![[E-Magazine] Springtime Conversation: Thanh Hoa - New Vision, New Aspirations](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2026/02/17/1771344033131_e-magazine-tro-w1200t0-di2607d272d1101804t11600l1-cover1.webp)

Comment (0)