Although not explained in great detail, through the press and information, we understood that the nation's protracted resistance war had entered its ninth year, having gone through the defensive and holding-off phase, and now it was "actively holding out in preparation for a general counterattack." Our army and people had won and were winning; our task was to transport food, supplies, weapons, and ammunition to the battlefield to support the troops fighting the enemy.

Long lines of carts on the road to the campaign.

None of us refused the task, but there were still some concerns because many people, although they knew how to ride a bicycle, didn't currently own one, and their families were poor, so how could they afford to buy one? The village team leader said: "Those who already have a bicycle should prepare it well and ride it. In difficult cases, the commune will provide some financial assistance for purchasing parts. As for those who don't have a bicycle, they will get one. The commune is encouraging wealthy families to contribute money to buy bicycles, and they will be exempt from civilian labor. In this way, those with resources contribute resources, and those with skills contribute skills: 'All for the front lines,' 'All to defeat the invading French.' Everyone felt reassured and enthusiastic."

So, after the meeting, within just 5 days, all 45 of us had enough bicycles to set off to serve. I received a brand-new "lanh con" bike that my uncle had contributed to the commune.

They were all new recruits, so they had to practice, from how to tie the handles to the carrying poles, load the goods, and then try carrying them on the brick courtyard, on village roads, and alleys to get used to it. At first, they could only carry a few steps before the cart tipped over, even though it wasn't heavy, with a maximum load of no more than 80kg. But they gradually got used to it. Besides practicing carrying goods, repairing the carts, and preparing to bring some necessary spare parts, everyone also had to study the policies, objectives, transportation plans, marching regulations, and the importance of the campaign, etc.

Our Thieu Do caravan crossed the Van Vac pontoon bridge at dusk, and the village girls bid us farewell with folk songs:

"No one in my village is in love."

I only love the soldier who carries the throne and the transport pole.

A few words of advice for my loved one.

"Complete the frontline mission and return."

We stopped at Chi Can village to organize the district's regiments and companies and pack supplies. Thieu Do platoon was tasked with transporting over three tons of rice to the front lines. The rice was packed into baskets, each weighing between 30, 40, and 50 kilograms. After packing, we marched northwest.

A convoy of bicycles carrying supplies on their way to the campaign.

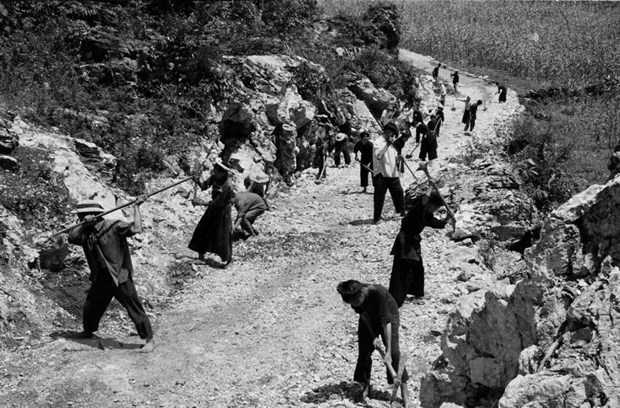

The Thanh Hoa - Hoi Xuan provincial road, once regularly used by passenger and cargo vehicles, is now riddled with mounds of earth blocking the way, dug up and cut into sections, each overgrown with banyan trees and thorny bamboo. The once straight road has become winding and bumpy, barely suitable for pedestrians, making cycling extremely difficult.

Every day, French enemy planes circled overhead, scanning the area. During the day, the road was sparsely populated, but as soon as the sun set, groups of people carrying loads and carts streamed out from the bamboo groves of the villages. At night, if one could count the stars in the sky, they could count the countless flickering, swaying lights of the laborers carrying supplies, winding along the road. As for us cart drivers, we used makeshift "underbody lights" that we attached to the front of our carts; the lampshade was the upper half of a white bottle cut in half, the float was for oil, and the wick was an ink bottle; the lampshade and float were placed inside a bamboo tube with a fist-sized hole cut out so that the light could shine through, enough to illuminate the road for the wheels to roll, as we had to be wary of the planes.

Traveling at night and resting during the day, it took us a week to reach the Cành Nàng station (Bá Thước). In total, we only covered about 10km each day. Upon arriving at Cành Nàng, we learned that a transport convoy from Thanh Hóa town was organizing a crossing of the La Hán River. The Cành Nàng station was located in the rear, a gathering place for civilian laborers from various districts in Thanh Hóa province, along with some from Nghệ An province.

Cành Nàng Street, the district capital of Bá Thước, was a gathering place for groups of laborers carrying goods on foot, using carts and boats, building roads and bridges, and leading cattle and buffaloes...

From morning till evening, the streets were silent, but at night they were bustling and lively, brightly lit with torches. "People and carts crowded the land, carrying loads like sardines." The sounds of shouting, singing, and calling out to each other echoed throughout the night. We met relatives from our hometowns who were transporting ammunition and supplies. Civilian laborers carrying supplies gathered here before crossing the Eo Gió pass to the Phú Nghiêm station. Civilian laborers using carts crossed the La Hán river and then traveled from La Hán to Phú Nghiêm and Hồi Xuân. More than a dozen ferries struggled from dusk till dawn to transport the Thiệu Hóa transport convoy across the river. Our unit had to march quickly to catch up with the Thanh Hóa town transport convoy. We arrived at Phú Nghiêm just in time to hide our carts when two Hencat planes swooped down and bombed the area. Fortunately, we managed to take cover in a cave. Phú Nghiêm had many caves, some large enough to hold hundreds of people, very sturdy. Thus, during the 10 days of marching, our unit had three close calls. This time, if we had been even a few minutes late, we would have been ambushed by the enemy en route, and casualties would have been unavoidable. The Thanh Hoa town group went ahead, followed by the Thieu Hoa group. Just as they left, two B-26 planes arrived and dropped dozens of bombs and rockets. However, amidst our good fortune, there was also the misfortune of our comrades and fellow countrymen: The bombing at Chieng Vac killed about ten people, and the shelling at Phu Nghiem also claimed the lives of two civilian workers who were cooking by the stream.

Scattered among the two convoys of pack animals, some had already retreated, unable to endure the hardships. The Thieu Hoa convoy rested for a day in Phu Nghiem to "train the officers and reorganize the troops," primarily to boost the morale of the unit members, heighten vigilance, and ensure adherence to marching regulations. This was necessary because some civilian workers had failed to comply with marching regulations, revealing their objectives. Furthermore, the enemy had sensed that we were launching a major offensive in the Northwest, so they were daily scanning our marching route with aircraft, bombing any suspicious areas.

After completing our "military drills," our group climbed the Yen Ngua slope to the Hoi Xuan station. The Yen Ngua slope is 5km long. It has 10 steps – so called because climbing is like scaling a ladder. Those carrying supplies trudged along, step by step, while on sunny days, three people had to push a cart up the slope; on rainy, slippery days, five to seven people had to work together, pulling and pushing. It was truly exhausting, with sweat pouring down our faces, just to get the cart up the slope. There's nothing more tiring than that, but after a short rest, we were as strong as ever. Going down the slope was even more dangerous, not only causing many cart breakdowns but also resulting in casualties.

The Thanh Hoa town team had a member who hit his nose on the road and died from crushing sugarcane pulp; the Thieu Hoa team had five or seven members who broke their arms and bruised their knees and had to be treated along the way before being forced to retreat to the rear. Going downhill, if it was a normal slope, you could just release the brakes and go, but on a steep slope, to be safe, you needed three types of brakes: In front, one person would firmly grip the handlebars with their left hand and push backward, while their right hand squeezed the front wheel to roll slowly; behind, another person would tie a rope to the luggage rack and pull it back, while the driver would hold the handlebars and poles to control the vehicle and the brakes. The brakes were small pieces of wood, cut in half and wedged under the rear tire; after several trials, this type of brake proved effective but very damaging to the tire. Later, someone came up with the idea of wrapping old tires around the wood wedge to reduce tire damage.

They marched at night and stopped at roadside huts during the day to eat and sleep. Sleeping was comfortable, but eating had to be very filling. On the front lines, rice, salt, and dried fish were readily available, and occasionally there was sugar, milk, beef, and sweets. As for wild vegetables, there was no need for rationing: wild greens, water spinach, passionflower, betel leaves, coriander, water taro... there was no shortage.

Through arduous journeys from their hometown to the Hoi Xuan station, the Thieu Do platoon lost three soldiers: one died of malaria, one had a broken cart frame, and one, unable to endure the hardships, died shortly after arriving at the Canh Nang station. The remaining soldiers joined over a hundred porters from the Thanh Hoa and Thieu Hoa town's civilian transport company, braving rainy nights and steep slopes with unwavering determination.

"It rained so hard my clothes got wet."

"Let's get wet so that the spirit of the laborers is uplifted."

And:

"Climb up the steep mountain slope"

"Only by participating in supply missions can one truly understand President Ho Chi Minh's contributions."

We arrived at Suoi Rut station on the very day our troops fired the first shots on Him Lam hill, marking the beginning of the campaign, and only then did we realize we were serving in the Dien Bien Phu Campaign.

If Cành Nàng was a gathering place for laborers from districts within Thanh Hóa province, then this place was also a meeting point for laborers from Sơn La, Ninh Bình, and Nam Định provinces. Though they were strangers, it felt as if they had known each other forever.

Laborers meet laborers again.

Like phoenixes and swans meeting, paulownia trees...

Laborers meet laborers again.

Like a wife meeting her husband, like a drought-stricken land receiving rain.

The Thieu Hoa transport unit was ordered to unload the goods into the warehouse. So, the rice from my hometown, sealed from home and transported here, is now safely stored in the warehouse and may be transferred to the front lines in a little while, or tonight, or tomorrow, along with rice from all other regions in the North.

After unloading the goods, we were ordered to withdraw to the Hoi Xuan station, and from Hoi Xuan we transported the goods to Suoi Rut. Hoi Xuan - Suoi Rut - Hoi Xuan, or abbreviated as VC5 or VC4 stations, we went back and forth like a shuttle, rejoicing at the successive victories reported from Dien Bien Phu.

The road from VC4 station to VC5 station, along the Ma River, has many shortcuts through local trails that have now been cleared and widened. Some sections are barely wide enough for handcarts to roll over freshly cut tree stumps. In some places, the road is built right up against a cliff face that has been eroded, requiring wooden platforms and bamboo slats to be placed against the cliff for people and vehicles to pass. Pushing the cart along these sections, I felt like I was traveling on the gravel road in Ba Thuc, as described in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms; a single misstep could send both me and the cart plunging into the river or the ravine.

The slopes here aren't long or steep, but most are vertical because the road crosses many streams, and each stream is a steep incline followed by an uphill slope. While on sections of the road to Hoi Xuan and La Han, it took three or four people to get a vehicle down a slope, here it took seven or eight people; the slopes were both steep and slippery. Sometimes it took half a day for the entire unit to get over the slope. That's why we could only travel five or seven kilometers each day, and we didn't have to travel at night because enemy aircraft were completely unaware of this stretch of road.

At night, with no shelters or camps, my comrades and I would lean our bikes against stakes, cover ourselves with raincoats, and sleep on sacks of rice. On rainy nights, we would simply put on our raincoats and wait for dawn. From VC4 to VC5, we received five days' worth of rice. That afternoon, after three days of marching, we stopped, parked our bikes by the Ma River, and just as we were about to set up a stove to cook, a heavy rain poured down. Everyone had to work quickly; two men at each stove stretched plastic sheeting to cover the fire until the rice was cooked.

It rained incessantly all night, and the rain didn't stop until morning; everyone discussed setting up tents to prepare for the prolonged downpour. Once the tents were set up, the rain stopped. Looking back at the road ahead, it was no longer a road but a river, because this was a newly opened road running along the riverbank next to the cliff. We waited a whole day, but the water still hadn't receded. Perhaps it was still raining upstream, we thought, and everyone was anxious and worried. Should we return to station VC4 or wait for the water to recede before continuing? The question was asked and answered. My platoon leader and I went on a reconnaissance mission. We waded into the water, leaning against the cliff face, carefully navigating upstream. Fortunately, the section of road around the cliff, less than 1km long, was wadeable; the water only reached our waists and chests. We returned and convened an emergency meeting. Everyone agreed: "At all costs, we must get the supplies to station VC5 as soon as possible. The front lines are waiting for us, all for the front lines!"

A plan was devised, and within hours we had finished building over a dozen bamboo rafts. We loaded the goods onto the rafts, lowered them into the water, and towed them upstream. However, it wasn't working out, as there were many sections with strong currents. Just when we thought we were doomed, the platoon leader came up with an idea: we built stretchers like those used for transporting the wounded. Four men per stretcher, each carrying two sacks of rice. We lifted the stretchers onto our shoulders and cautiously waded upstream: Hooray! Transporting rice like transporting the wounded! After nearly a full day submerged in water, the unit managed to transport over three tons of rice across the flooded section and deliver it in time to the VC5 station. At this time, hundreds of civilian workers were waiting for rice at the VC5 station. How precious the rice was at the station at this moment!

As the floodwaters receded, we returned to station VC4 and then from VC4 to VC5. On the day the whole country rejoiced at the victory at Dien Bien Phu, the 40 of us porters returned to our hometowns, proudly wearing the "Dien Bien Phu Soldier" badge on our chests.

Source

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends the ceremony commemorating the 80th anniversary of the establishment of May 10 Garment Corporation.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F08%2F1767888283715_ndo_br_tttrao-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] High-altitude schools proactively take measures to protect students from the cold.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F08%2F1767883787301_a34-9332-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)