Lacking the support of modern technology, ancient people needed a lot of time to make maps and had to synthesize information from many different sources.

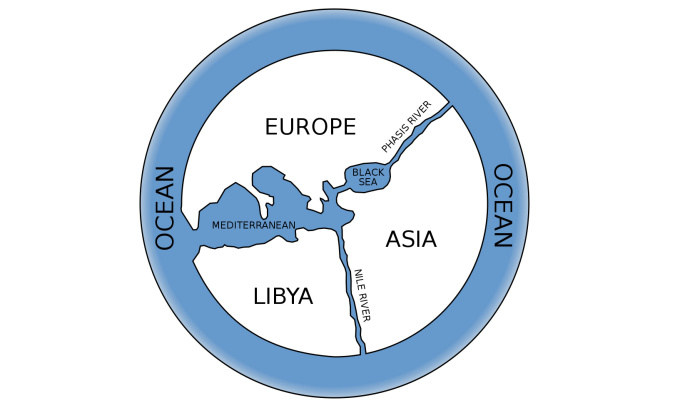

Anaximander's map of the "known world ". Photo: Wikimedia

Ancient mapmakers relied on a combination of art, exploration, mathematics, and imagination to capture the vastness of the lands they knew and the many they believed existed. In many cases, these early maps were both navigational aids and mystical revelations.

It took the ancients a long time to make maps. Maps were the result of generations of travelers, explorers, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, historians, and other scholars piecing together fragments of information. As a result, early works were based on some actual measurements, but also on much speculation.

One of the first detailed descriptions of the "known world" was made by Anaximander, a philosopher who lived around 610 - 546 BC and is considered one of the Seven Sages of Greece. The phrase "known world" is emphasized, because Anaximander's circular map shows the Greek landmass (at the center of the world) and parts of Europe, South Asia and North Africa. To the sage, these continents were joined together to form a circle surrounded by water. The Earth was considered flat at that time.

In the 1st century BC, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, a Greek polymath, calculated the circumference of our planet by comparing the results of surveys collected in the Library of Alexandria. Although many people previously believed that the Earth was round, modern scientists have no record of how they measured the Earth's circumference. Eratosthenes was an exception.

Eratosthenes' method was simple and anyone can do it today. He measured the length of the shadow cast by a vertical stick in two cities on the same day. The north-south distance between the two cities and the measured angles provides a ratio that allows him to calculate the Earth's circumference with relative accuracy (about 40,000 km). After Eratosthenes published his results, flat-Earth maps continued to circulate for a while but eventually disappeared.

Eratosthenes also developed a method for locating places more precisely. He used a grid system—similar to that found on modern maps—to divide the world into sections. This grid system allows people to estimate their distance from any recorded location. He also divided the known world into five climatic zones—two temperate zones, two polar zones to the north and south, and a tropical zone around the equator. This creates a much more complex map that shows the world in great detail.

In the following centuries, maps became more complex as Roman and Greek mapmakers continued to collect information from travelers and armies. Compiling the documents, the scholar Claudius Ptolemy wrote the famous book Geographia and the maps based on it.

Ptolemy's work, compiled around 150 AD, relied heavily on older sources. What made Ptolemy so influential, however, was that he provided a clear explanation of how he created his work so that others could copy his techniques. Geographia contains detailed coordinates for every location he knew of (over 8,000). Ptolemy also introduced the idea of latitude and longitude, which people still use today.

Geographia was introduced to Europe in the 15th century. Over the years, Muslim scholars reviewed, examined, and even revised Ptolemy's work. His work, along with new maps by influential geographers such as Muhammad al-Idrisi, became extremely popular with explorers and mapmakers in the Netherlands, Italy, and France in the mid-18th century.

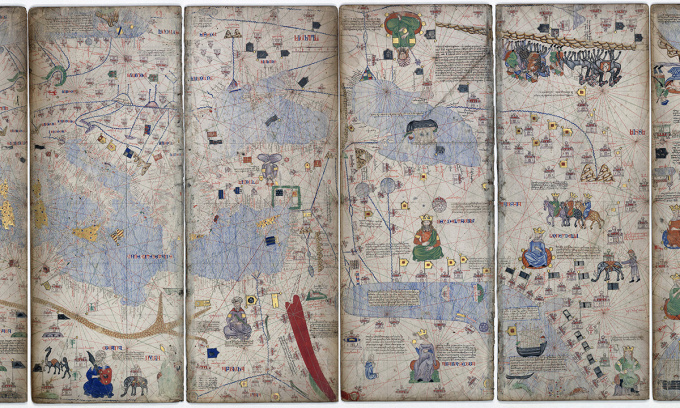

Part of the Catalan Atlas. Photo: Wikimedia

A major development in mapmaking was the invention of the magnetic compass. Although knowledge of magnetism had existed for a long time, its application to reliable navigational devices did not begin until around the 13th century. The compass rendered many older maps obsolete for navigation. Next came the portolan chart, a nautical guide used to navigate between ports.

A prominent example of a portolan map is the Catalan Atlas, created by cartographers for King Charles V of France. They created the map by synthesizing information from a variety of sources. It is unclear exactly who created it, but many experts attribute it to Abraham Cresques and his son, Jahuda.

The Catalan Atlas is filled with information about real places, but it also contains many fantastical details. This problem arose from the compilation of maps from many different sources, including travelers' stories and myths. As a result, beasts, dragons, sea monsters, and imaginary lands continued to appear on many maps long after.

Thu Thao (According to IFL Science )

Source link

Comment (0)