The water at Blood Falls in Antarctica is bright red because it contains iron in the form of microspheres 100 times smaller than human red blood cells.

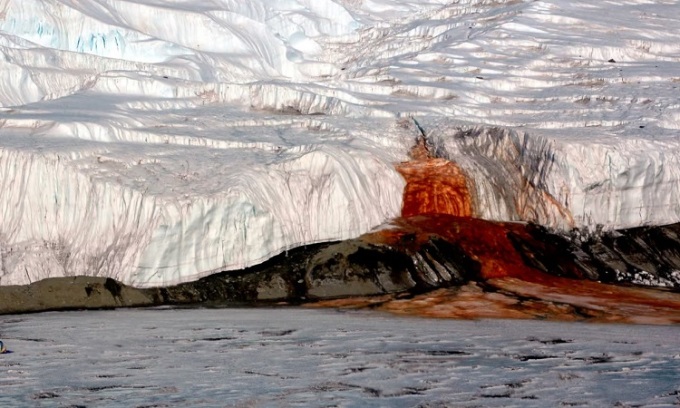

Blood Falls at Taylor Glacier. Photo: Peter Rejcek

Bloody waterfalls pour from the base of Taylor Glacier. A team of researchers announced the discovery of the mystery behind the red water of Blood Falls in Antarctica in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, New Atlas reported on June 27.

The strange phenomenon was first discovered in 1911 by geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor, who attributed it to red algae. Just half a decade later, researchers determined that the red color of the water was caused by iron salts. Most notably, the water was initially clear but quickly turned red after flowing from the ice, as the iron oxidized when exposed to air for the first time in millennia.

However, new research examining water samples found iron in an unexpected form. It is not a mineral, but rather a microscopic sphere 100 times smaller than a human red blood cell.

"As soon as I looked at the microscope image, I noticed that there were many small iron-rich microspheres. In addition to iron, they contained many other elements such as silicon, calcium, aluminum, sodium. They were very diverse," said Ken Livi, a co-author of the study. "To be a mineral, the atoms must be arranged in a specific crystal structure. Microspheres are not crystalline, so previous methods for examining solids could not find them."

A few years ago, scientists discovered that the water in Blood Falls originated in a subglacial lake that was extremely salty, under high pressure, and without light or oxygen. An isolated ecosystem of bacteria had survived in the lake for millions of years. Life may have existed on other planets in similarly harsh conditions.

"Our study reveals that rover-based analysis is incomplete in determining the true nature of environmental materials on planetary surfaces. This is especially true for colder planets like Mars, where the materials formed may be nanoscale and not crystalline. Understanding the nature of rocky planet surfaces requires electron microscopy, but we currently cannot send such equipment to Mars," Livi said.

An Khang (According to New Atlas )

Source link

![[Photo] Magical moment of double five-colored clouds on Ba Den mountain on the day of the Buddha's relic procession](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/9/7a710556965c413397f9e38ac9708d2f)

![[Photo] Russian military power on display at parade celebrating 80 years of victory over fascism](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/9/ce054c3a71b74b1da3be310973aebcfd)

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam and international leaders attend the parade celebrating the 80th anniversary of the victory over fascism in Russia](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/9/4ec77ed7629a45c79d6e8aa952f20dd3)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs a special Government meeting on the arrangement of administrative units at all levels.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/9/6a22e6a997424870abfb39817bb9bb6c)

Comment (0)