The ancients could actively mummify bodies ritually, but the process could also occur naturally under special conditions.

Mummies have been found on every continent on Earth, including mummified penguins in Antarctica. The key to natural mummification is to disrupt the natural stages of decomposition by making it difficult for the microorganisms and enzymes that break down the body after death. This can be achieved in conditions of extreme cold, extreme dryness, acidic environments, or the absence of oxygen.

Chinchorro mummies in the San Miguel de Azapa archaeological museum in Camarones, Arica, Chile. Photo: Martin Bernetti/AFP

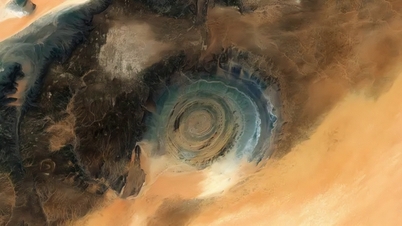

Desert Mummies

In dry conditions, the human body can mummify itself due to lack of water. In extremely hot and dry environments, the body is able to lose water quickly enough before microorganisms and enzymes can break down most of the tissue, helping to preserve the body in a relatively good condition.

Most enzymes function in an aqueous environment. Therefore, a lack of water will slow down decomposition or even stop it. In spontaneous mummification, the body's natural dehydration occurs more quickly than the development of enzyme activity, according to the book Taphonomy of Human Remains: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment by Eline M.J. Schotsmans, Nicholas Márquez-Grant, and Shari L. Forbes.

However, the body does not always dry evenly. Some parts such as the hands and genitals will lose water relatively quickly, but internal organs such as the heart will take longer.

A famous example of a desert mummy is the Chinchorro mummies of the Atacama Desert. Some are likely to have been deliberately mummified and are up to 7,000 years old – 2,000 years older than the oldest Egyptian mummies. However, older mummies are thought to have formed naturally due to the desert environment and may be up to 9,000 years old.

Tollund Man, a bog mummy dating back about 2,400 years. Photo: Tim Graham / Getty

Swamp Mummies

Another effective way to induce natural mummification is to place the body in a peat bog. Experts have found large numbers of these bog bodies in northern Europe, especially Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, Ireland and England.

If immersed in peat bogs, the body will be exposed to cold, highly acidic water and lack of oxygen. In addition, some unique chemical reactions here will promote the mummification process.

A key factor is the type of vegetation found in peat bogs. These are often dominated by Sphagnum moss, which grows on the surface of the bog. The lower layers of the bog are filled with decaying Sphagnum moss. When the moss dies, it releases a polysaccharide called sphagnan, which has properties that help remove metal ions from a solution. As a result, some metal ions, such as iron, copper, or zinc, are no longer available to bacteria, depriving them of a vital nutrient, according to the book Taphonomy of Human Remains: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment.

These harsh conditions prevent microorganisms from starting the decomposition process, although the bones will eventually corrode in the acidic environment. As a result, the body turns brown, preserving the skin, hair, and nails.

The most famous example of a bog body is Tollund Man, discovered by peat diggers in the Jutland peninsula of Denmark around the 1950s. When first seen, people assumed he was a boy who had recently gone missing in the area. However, analysis has shown that the mummy is much older, dating back 2,400 years. The mummy is so well preserved that scientists even know what his last meal consisted of.

The natural mummy known as "Otzi the Iceman", discovered in the Alps in 1991. Photo: Andrea Solero/AFP

Ice Mummy

Cold and icy environments are also ideal for natural mummification. Most enzymes involved in decomposition are inactive at sub-zero temperatures, so they cannot break down body tissue.

Ötzi the Iceman is a classic example of this type of natural mummification. His body was discovered in the Alps on the Austrian-Italian border in 1991. Austrian authorities initially assumed he was a modern-day mountaineer because of his excellent preservation. However, he actually died around 5,300 years ago.

Rising global temperatures are melting more glaciers, ice caps and permafrost, meaning discoveries like Otzi the Iceman could become more common in the future.

Thu Thao (According to IFL Science )

Source link

![[Photo] 60th Anniversary of the Founding of the Vietnam Association of Photographic Artists](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F05%2F1764935864512_a1-bnd-0841-9740-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man attends the VinFuture 2025 Award Ceremony](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F05%2F1764951162416_2628509768338816493-6995-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)