For 180 years, experts have not found the exact cause of the light and dark ripples that move when the Sun is obscured.

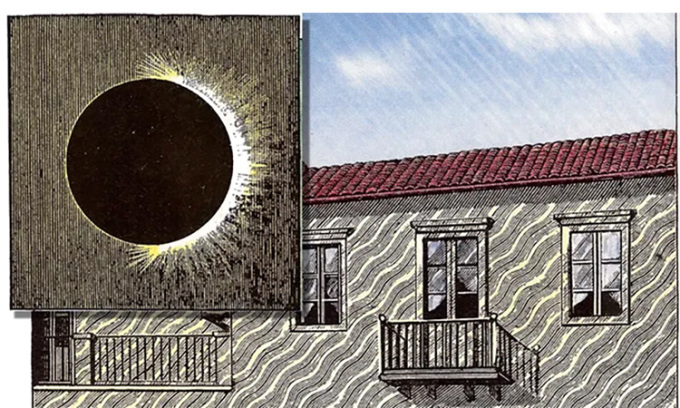

Simulation of the shadow bands that appear as the Sun narrows into a thin band of light during a total solar eclipse. Photo: Sky and Telescope Magazine

The first total solar eclipse of 2024 will take place on April 8. For many, it will be a great opportunity to see the corona—the Sun’s outer atmosphere—as well as the stars and planets that appear during the day. But there’s another unusual phenomenon that can only be seen when the Sun has shrunk to a single thread of light: shadow bands.

Shadow bands are wavy bands of light and dark that can appear on flat surfaces. “It’s like being at the bottom of a swimming pool,” says astronomer Nordgren. Shadow bands remain a scientific mystery. Astronomers don’t know exactly what causes them or why they only appear occasionally.

Of all the phenomena that occur during a solar eclipse, shadow bands are perhaps the most unusual. These mysterious ripples are sometimes seen gliding across the ground in the minutes before totality (when the Sun’s disk is completely obscured by the Moon). Initially, the bands appear faint and haphazard, but as totality approaches, they become more organized, the distance between them decreases to a few centimeters, and they become more distinct. After totality ends, the opposite happens: the shadow bands reappear, gradually becoming fainter and more haphazard, and finally disappearing altogether.

However, within the same eclipse, observers in different locations will see different shadow banding effects. Some report that shadow banding is almost impossible to see, while others see it quite clearly. During some eclipses, shadow banding is quite vivid and easy to see, but during other eclipses, it is very faint or completely invisible.

Scientists are not certain when shadow bands were first observed. According to amateur astronomer George F. Chambers’ book, The Story of Eclipses , the phenomenon was first recorded during the solar eclipse of July 8, 1842. By 1878, observers in Colorado, USA, were preparing for the appearance of “diffraction bands.” The lack of shadow banding observations before the mid-19th century may be due to the fact that many people focused their gaze upward during eclipses rather than downward.

Shadow bands are also very difficult to photograph. They usually appear when only about 1% of the Sun is not obscured by the Moon, so there is very little light and very low contrast. The average speed of shadow bands moving across the ground is about 3 meters per second. Shadow bands are also usually only a few centimeters wide, so they appear blurry in photos or videos . There is also a physiological reason why shadow bands are not recognizable in most photos. They are much easier to see when moving than when stationary.

Shadow bands during the total solar eclipse of June 21, 2001. Photo: Wolfgang Strickling/Wikimedia Commons

Over the past 180 years or so, experts have proposed various ideas to explain the shadow bands. One of the earliest explanations was that they were diffraction bands. These occur when light waves pass through a narrow slit in a solid surface, creating a dark stripe in the middle and brighter stripes on each side. Then, in 1924, Italian astronomer Guido Horn-D'Arturo suggested that the bands were superimposed pinholes of the Sun, formed by spriragli – gaps in the Earth's upper atmosphere.

The most likely explanation is a meteorological effect, caused by the last rays of sunlight being distorted by the Earth’s turbulent atmosphere. This effect also distorts the light from distant stars, making them appear to twinkle. Starlight is distorted because, when viewed from Earth, a star is a point source. Bright planets such as Venus and Jupiter, which are clearly visible to the naked eye, are not point sources, but much larger. As a result, they rarely appear to twinkle, even when very close to the horizon.

The Sun and Moon do not normally twinkle. But during a solar eclipse, when the Sun’s disk is reduced to a thin filament of light, each point along the filament appears to twinkle like a star. The shadow bands may therefore be the result of light being emitted from each point. Some experts believe that the worse the viewing conditions (due to atmospheric turbulence) the more vivid the shadow bands appear.

Thu Thao (According to Space )

Source link

![[Photo] Closing of the 1st Congress of Party Delegates of Central Party Agencies](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/24/b419f67738854f85bad6dbefa40f3040)

![[Photo] Editor-in-Chief of Nhan Dan Newspaper Le Quoc Minh received the working delegation of Pasaxon Newspaper](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/23/da79369d8d2849318c3fe8e792f4ce16)

Comment (0)