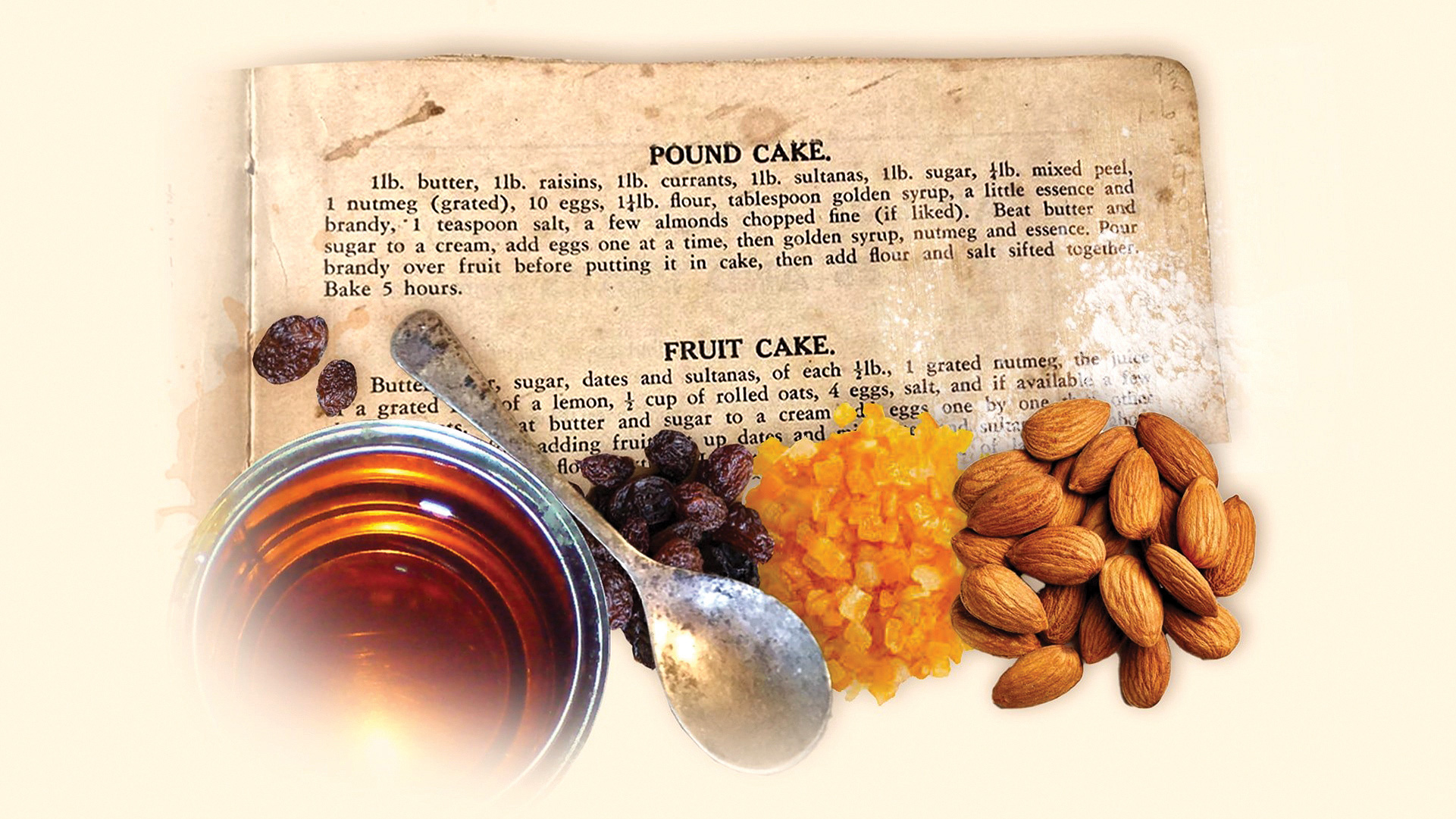

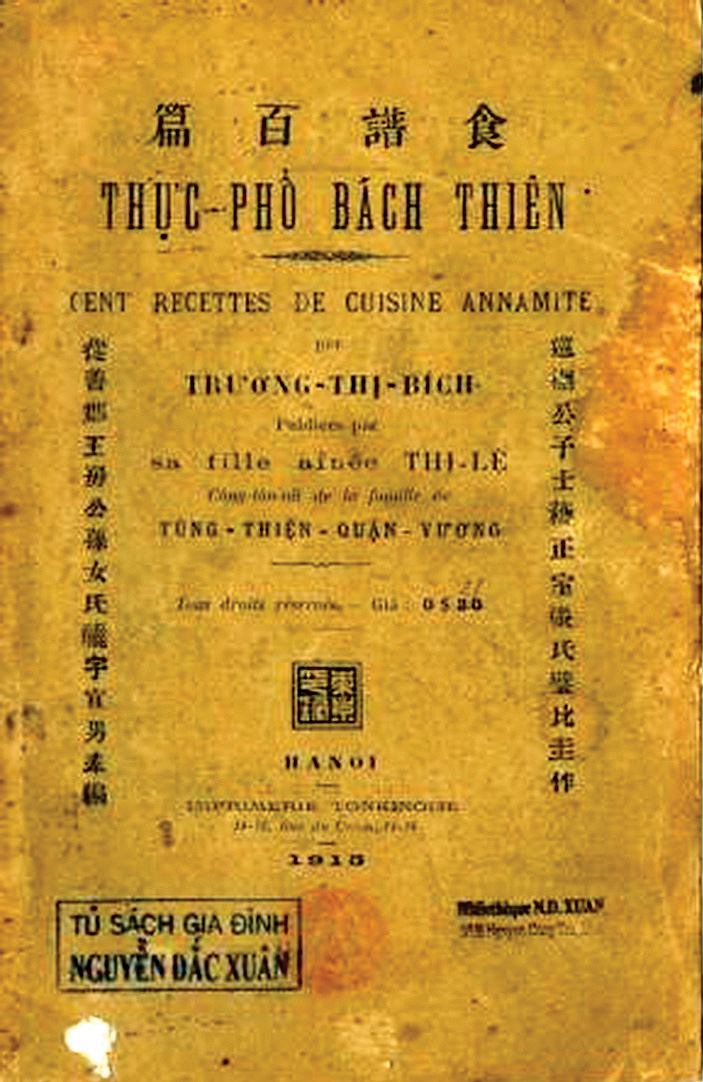

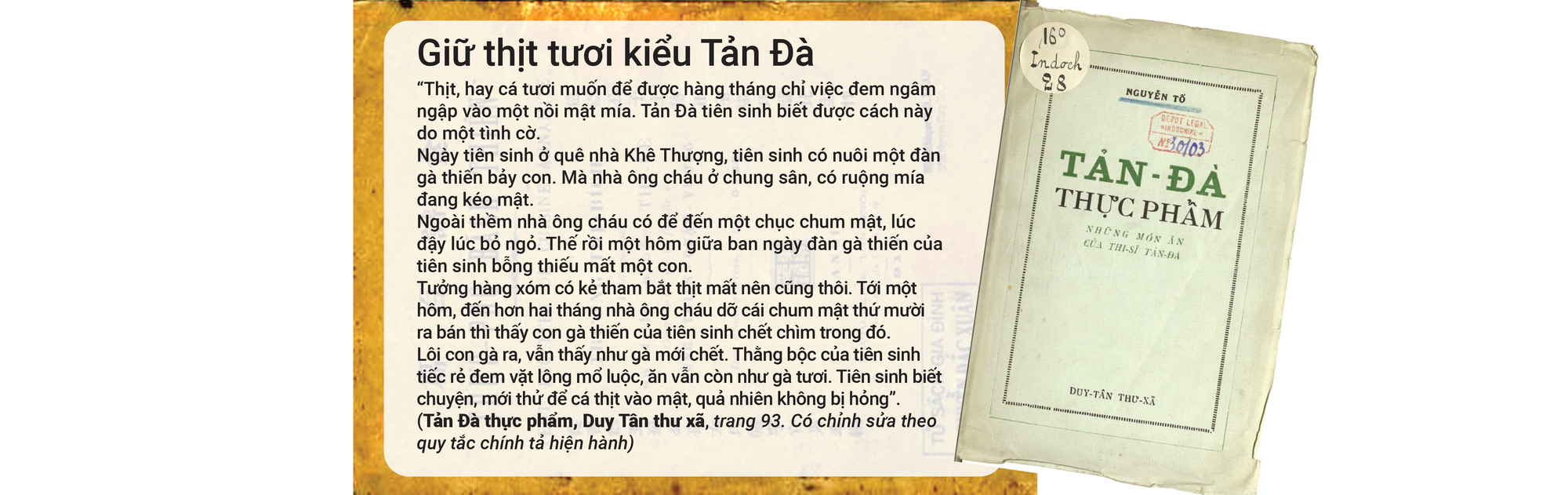

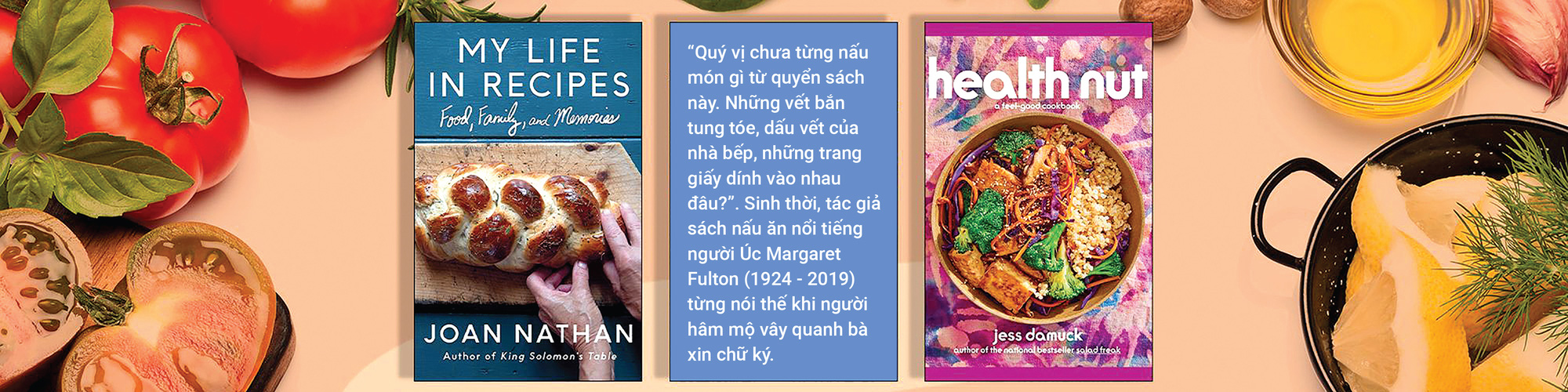

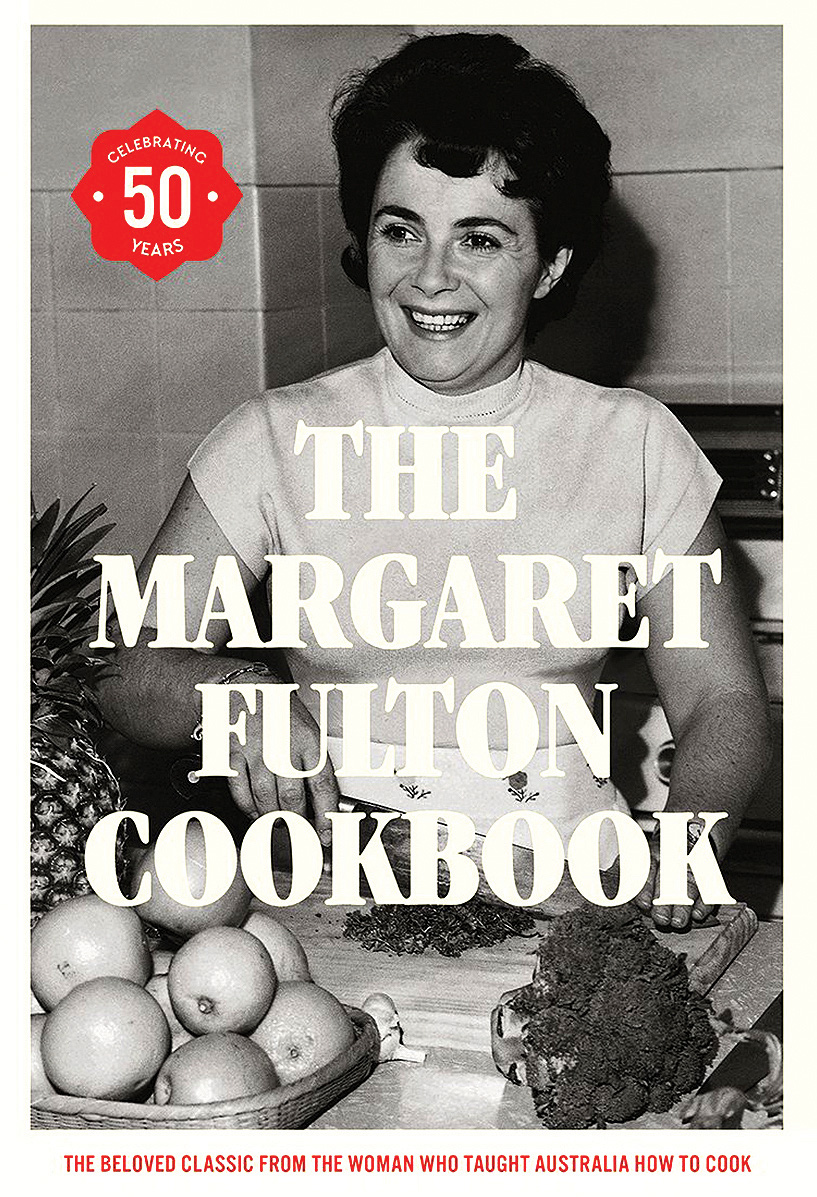

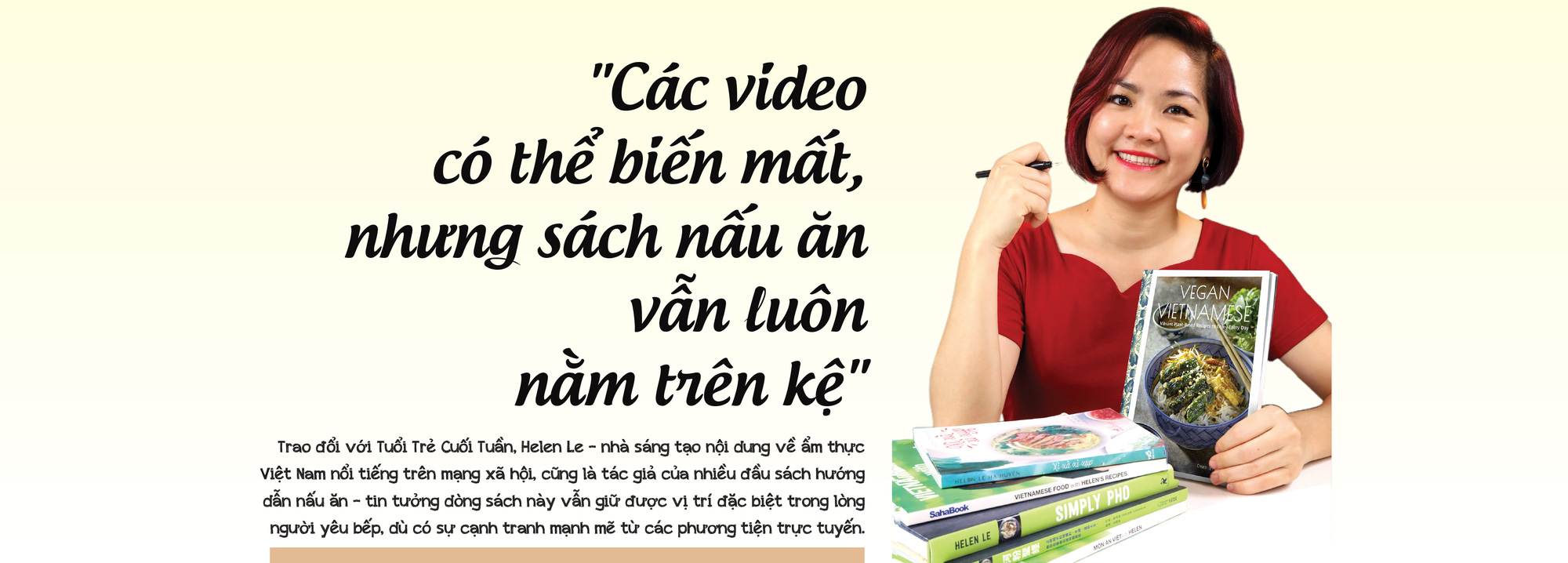

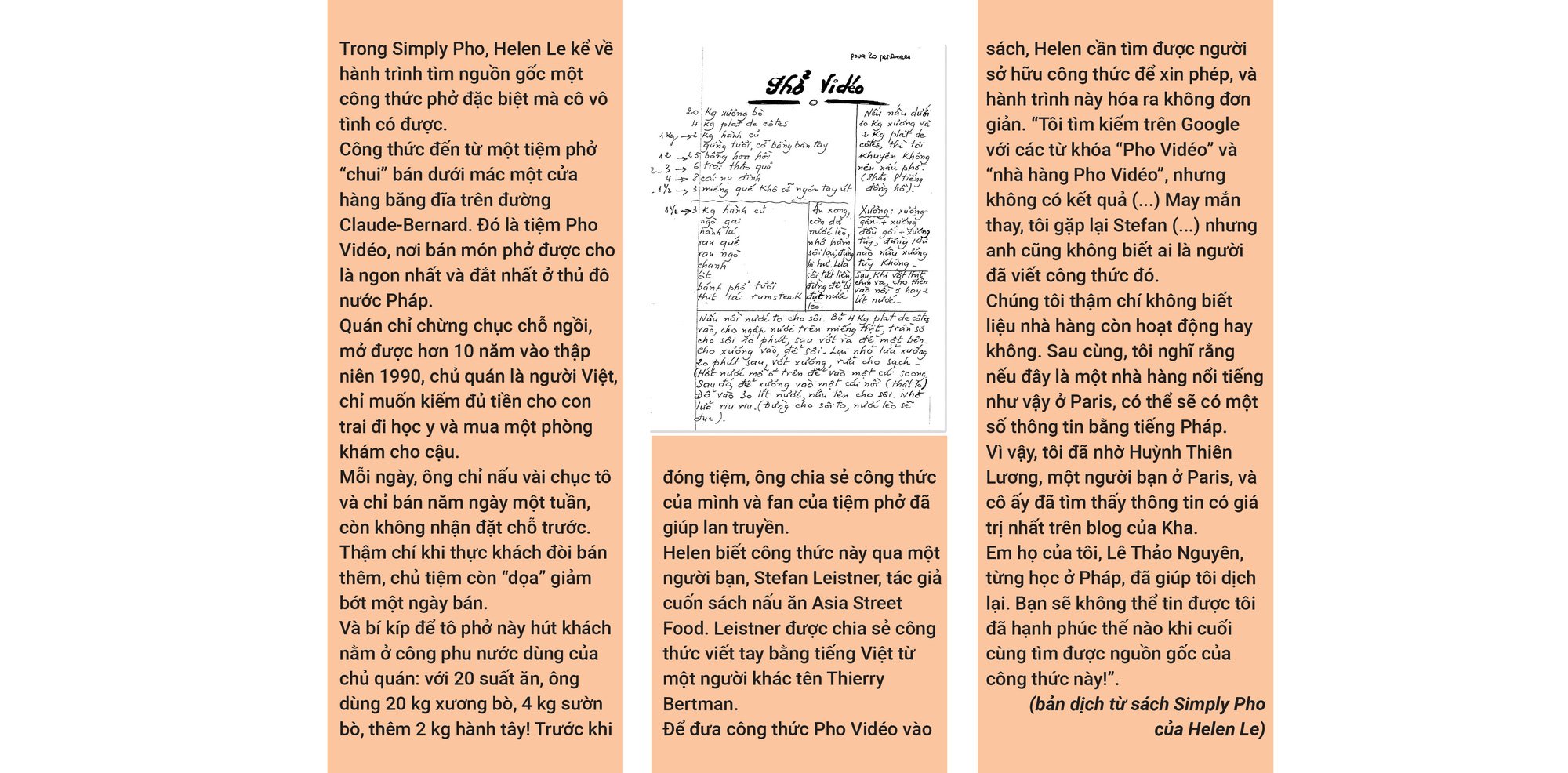

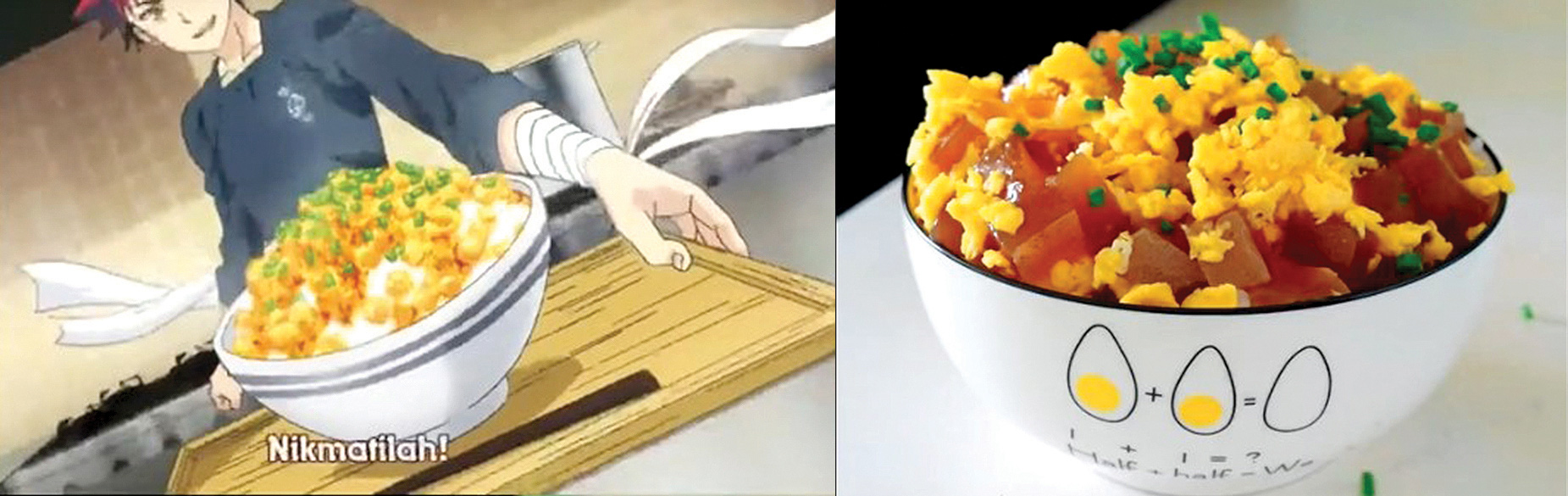

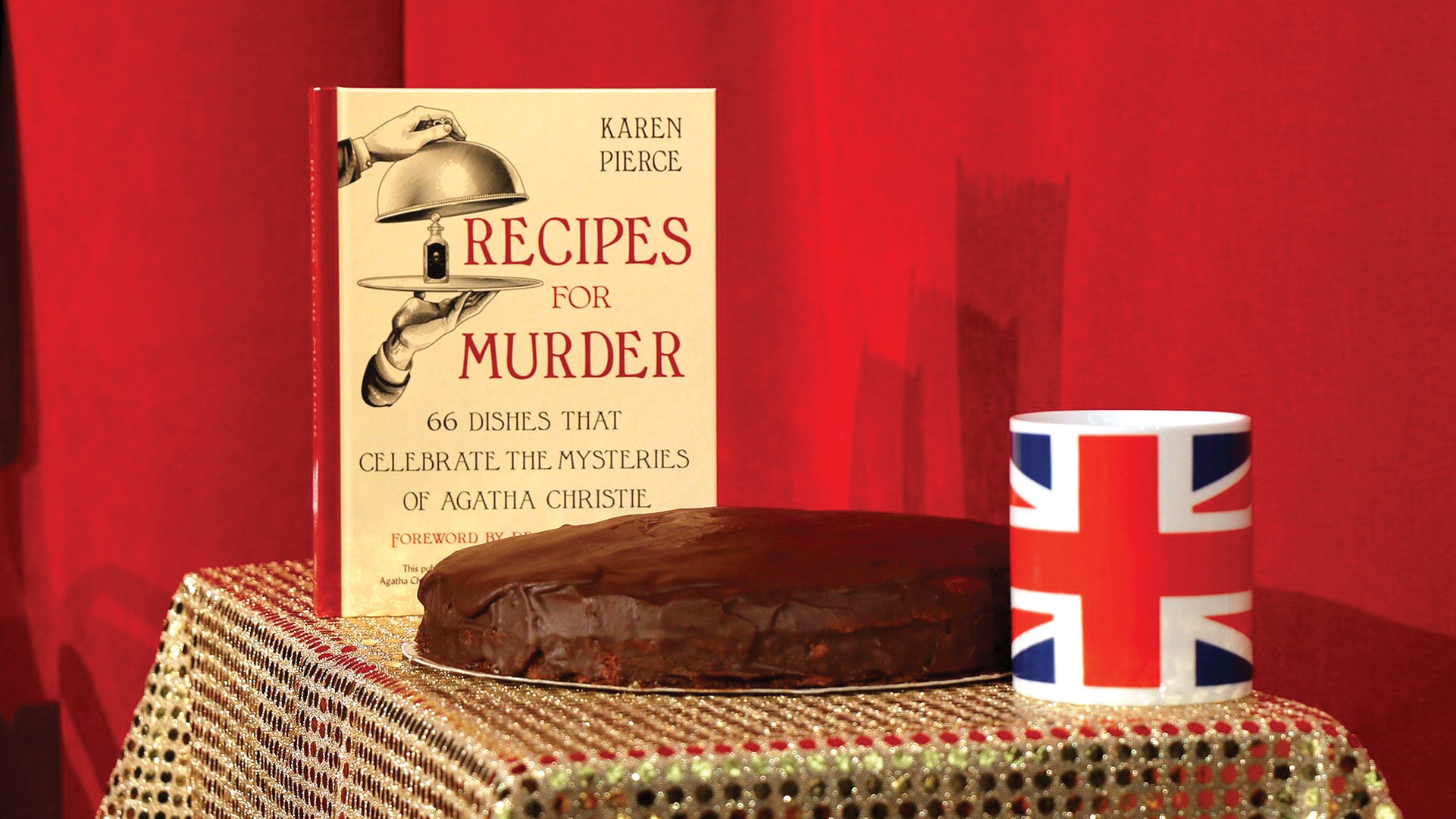

Reading old cookbooks carefully reveals that they bring us more than just nostalgia and family memories. Another Australian, ABC News journalist Emma Siossian, refers to cookbooks as “snapshots”—instant snapshots of who we are and where we came from. As an example, she tells the story of making a Christmas sponge cake from a recipe in Janet Gunn’s family’s literal family cookbook. The book was first owned by Gunn’s grandmother, who bought it in the 1930s. During World War II, Gunn’s mother made a sponge cake using the same recipe and had it delivered to her father, who was serving in New Guinea, by the Red Cross. Today, next to the recipe, there is still a handwritten copy of the price of each ingredient that her mother carefully recorded at that time. Gunn also keeps the handwritten recipe books written by her grandmother, mother and mother-in-law, which she treasures very much. It’s not just the history of an individual or family. Reading old books, we can see the ups and downs of life, as well as the lists of ingredients and the meticulous instructions on how to cook. For example, according to Siossian, rereading The Barossa Cookery Book, one of Australia’s oldest recipe collections, shows what the status of women was like in the past. The Barossa Cookery Book was first published in 1917, and was reprinted several times in the following years until the revised edition was released in 1932. In the original edition, the female authors were not even named, but referred to only by the initials of their husbands. Two modern-day women, Sheralee Menz and Marieka Ashmore, are leading a project to trace the past, hoping to find the names of those women and their life stories, so that they can be given the credit they deserve. Avery Blankenship, a doctoral student at Northeastern University (USA), also made a similar discovery about the "authorship" of ancient recipes. Accordingly, in the 19th century, the person whose name was on the cookbook - a type of book that was extremely important to new brides at that time - was not the real "father" of the recipes in it. Noble homeowners often hired people to copy recipes created by their cooks or slaves in the house, and compile them into books. Of course, those half-literate slaves did not know that they were completely unnamed and did not receive any recognition for their contributions. Cookbooks, Wessell argues, are also a database for charting changes such as migration, the availability of different ingredients, and technological changes. For example, Blankenship analyzes Elizabeth Smith Miller’s 1875 book In the Kitchen, which traces the transition from narrative recipe writing to the more scientific , ingredient-filled, and quantitative form we see today. Readers of the book can also learn about post-Civil War America. Some of its recipes, like the one for bacon, offer a more comprehensive historical view of slavery in the United States at the time. Emily Catt, curator of the National Archives of Australia, which houses the country’s vast cookbook collection, says the recipes also reflect the challenges of the times. Writing for History News Network in July, Blankenship argued that reading old recipes is an art, because hidden within them can be a surprising treasure trove of history, relationships, and changing perceptions. The book raises the question: who exactly is “in the kitchen,” and who has the right to be considered a role holder in that space? She admits that reading recipes that require “unknowns” and historical and cultural connections is not pleasant, but those who master this “art” will gain a lot of enlightenment. “(This) helps reveal women who may have been forgotten by history and, more broadly, raises questions about the origins of culinary traditions, about how many hands toiled in the making of those culinary histories. The same approach can be applied to your own family cookbooks: where did your grandmother’s recipes come from? Who were her closest friends? Whose cakes did she like best? Which names are mentioned and which are hidden? These are important questions that await answers—though they may never be fully answered,” Blankenship writes. First, the earliest appearance is probably the Annamese Cookbook (1) by author RPN, published by Tin Duc Thu Xa, Saigon in 1909, according to information saved on Google Books. Next in order are Annamese Cooking Book (2) by Mrs. Le Huu Cong, Maison J. Viet, Saigon in 1914 and Thuc pho bach thien (3) by Truong Thi Bich (pen name Ty Que), published by the family, printed in Hanoi , 1915. Particularly noteworthy is the book Tan Da Thuc Pham (4) by Nguyen To, who claimed to be the poet's disciple, recording Tan Da's eating life from 1928 to 1938. The book was published by Duy Tan Thu Xa in 1943, including 74 homemade dishes of "chef" Tan Da. Each dish at that time did not cost more than 2 dong - calculated according to the equivalent gold price today, it is about 280,000 dong, which is also very luxurious. Another document said that at that time, a bowl of pho was only a few cents; even if it was 5 cents, then 2 dong was 40 bowls of pho. The only thing is, I don’t know where the poet got the money to buy wine and cook food every day. Let’s take a look at three traditional Vietnamese recipes (1, 3 and 4) that represent the three regions mentioned above, to see how some of the most common Vietnamese dishes are cooked/prepared. Although everyone says that the dish of fish cooked with am is a specialty of their hometown, it is available all over the country. It is available in books by RPN (Saigon), by Mrs. Ty Que ( Hue ), and by Tan Da (Hanoi). According to the Vietnamese dictionary by Le Van Duc, "pork porridge (am) has a lot of pepper, eaten hot to make you sweat". This meaning is quite similar to the meaning of "am" in the Annam - French dictionary (1898) by Génibrel: pleasant. Comfort food - a refreshing dish? Nowadays, snakehead fish, striped snakehead fish and snakehead fish are the common denominators in the dish "cooking porridge". Snakehead fish is called "ca" in the South, snakehead fish is called "ca" in the South. People in the West say that snakehead fish is not as delicious as black snakehead fish, while people in the North say the opposite. I believe people in the West more, because that is the place where snakehead fish are widely available, they have the opportunity to erode their teeth to make a judgment "better". Types of snakehead fish generally include black snakehead fish, thick snakehead fish and "hanh duong" fish, but that common denominator has an exception in the dish "cooking fish" of "drunken devil" Tan Da, who prefers to choose carp or mullet (sea carp). But with a high-level fish with small bones like carp, our drunken poet has to go through a process of making the bones rot, but the fish's meat is still firm. The respectable thing about Tan Da is his tasteful way of eating: "The pot of porridge is always kept on the stove to boil. When eating, put the vegetables in the bowl, cut a piece of fish, dip it in shrimp paste, lemon, chili, and water beetles, put it on top and eat. Chew the fish and vegetables thoroughly, then scoop a few spoonfuls of hot porridge and slurp." Ancient cuisine is no less than today's Michelin cuisine! It's better, if you count Tan Da. In some places in the past, porridge was turned into soup like the fish stewed in am today. Like "Canh ca trau canh am" by Truong Thi Bich: "Canh ca trau canh am is skillfully made with the offal/ Braised onion fat with clear fish sauce/ Sweet shrimp paste, enough pepper and chili/ Tomatoes, ripe star fruit, and it's done". Chicken was once a dish that could be eaten quietly without neighbors knowing. In that situation, repression led to the creation of many chicken dishes outside of old books. It is worth mentioning that the ancient way of cooking "tiêm" was to use green beans, peanuts, jujubes, lotus seeds, black fungus, and shiitake mushrooms, stuffing them into the chicken's gizzard, then simmering until cooked. The broth was used as soup (thang). The stewed chicken "guts" were used as the main dish. In the past, Chinese families who held memorial services often did charity work by taking out the chicken intestines to eat with the soup and giving the chicken to beggars. Nowadays, "tiêm" is completely different from the past. For example, green chili chicken stew uses chili leaves and chili peppers to cook hot pot with a pre-cooked chicken. The chicken is cooked to the degree that the diners want it to be, no longer the soft charm of the old days. Mrs. Bich has two chicken dishes with the following poem, reading them, you immediately know what the dish is without introduction: "Skillfully stewed chicken, the water is clear/The fish sauce is seasoned with sour and salt/The bamboo shoots and mushrooms are put in a little pepper/The green onions are used to make the dish"; "The young chicken is skillfully steamed until it is sweet and soft/Tear it into small pieces and then sprinkle with water/Sprinkle with salt and pepper and knead well/Rub in Vietnamese coriander and cinnamon leaves." Tan Da's chicken dish is more elaborate: fake peacock spring rolls. He chooses a fat young hen, burns it over a fire to remove the down feathers, filters out two loins (breasts), rubs them with salt, chops them finely and mixes them with chopped cooked pork skin (not pounded like the Southern people), mixes with finely ground roasted salt and glutinous rice powder. Wraps it in young fig leaves, with banana leaves on the outside. Hangs it up for three days to make it sour. Eats it with crushed garlic salt. Compared to peacock spring rolls, which he has eaten several times, he thinks it is not inferior. Vietnamese fish sauce has recently been on fire like a ripe charcoal fire in the kitchen. Vietnamese people do not call fermented salted plants fish sauce, so this article does not mention soy sauce and soy sauce. In discussing fish sauce, author RPN may have been infected with the West, with "fishpaste-phobia", only passing it over in "Chapter VII, Fish Sauces". Later, Mrs. Bich of Hue "lived a culinary life" with a very rich fish sauce, especially with shrimp paste as MSG. In the book, there are 40 of her dishes seasoned with "fish sauce" and additives to soften (sugar, shrimp, shrimp, meat...), create aroma (garlic, onion, ginger, pepper, sesame), create fat (fat), create sourness (star fruit). There is a recipe for "cooking fish sauce" with 4 types of fish: "Doi, Dia, Ngu, Nuc, marinate how much/ Fish sauce is condensed for a long time, it looks like there is a lot/ Grill the bones of the animals, wrap them in a towel and cook/ Filter carefully with a thick cloth, the water is clear". Her fish sauces are also very unique: "Fake shrimp paste", "Crab roe sauce", "Sour shrimp sauce" (a dish whose taste is unknown but seems to be more famous than the famous sour shrimp sauce of Go Cong), "Nem sauce", "Tuna sauce", "Tuna intestine sauce", "Tuna sauce, mackerel sauce with powdered rice", "Doi sauce, dia sauce with powdered rice", "Anchovy sauce", "Mam nem ca mac", "Mam nem mac bo chili tomato", "Mam nem canh" and "Ruoc khuyet". There are 12 kinds of fish sauces in total. People in the West today have to take their hats off to people in Hue. Going to Hanoi, getting lost in Uncle Tan Da's fish sauce world, they become even more naive and strange. The fish sauces he made himself included "Cai fish sauce", "Pork rib fish sauce", "Tuna fish sauce", "Thuy Tran fish sauce" (a type of small shrimp that "looks like bran" and is popular in the season after Tet), "Rươi fish sauce", "Finger shrimp sauce" (as big as a finger), "Riu shrimp sauce, rice shrimp sauce", "Lanh fish sauce" (carp family, small fish), "Ngan fish sauce", "Roe fish sauce". It should be added that in the early 1900s, the instructions of author RPN were not concise and difficult to follow. Each quatrain for a dish by Mrs. Ty Que was even more difficult to understand, especially since there were quite a lot of Hue dialects... Reading old books and comparing them with today's books, it goes without saying that there have been many changes. Following a recipe to create a delicious dish is no longer the ultimate goal of cookbooks, for both the writer and the reader. Although they no longer have the superstar status they had before the advent of cooking shows on television and recipes flooding the internet, cookbooks still sell, even if not everyone who buys them does so to learn from them. They brought a yellowed original copy of The Margaret Fulton Cookbook (1969), proudly reporting that her book had been passed down through generations - given to each after they moved out and started families. Fulton would then smile sweetly and flip through the pages as if searching for something. Then she would close the book, looking at them with a face of pretended annoyance and "loving reproach" as above. This is a memory of her grandmother Margaret Fulton as told by food writer Kate Gibbs in The Guardian in late 2022. Gibbs said this is proof that going into the kitchen and following a recipe can only play a supporting role in a cookbook. So what do people buy them for? "Partly for daydreaming. People imagine dinner parties, gatherings, a neatly set table and engaging conversations. Just like how we buy fashion magazines like Vogue when we have no intention of taking off the sandals we are wearing, or read beautiful home magazines when we can't even afford rent" - Gibbs wrote. Indeed, nowadays, if you want to find a recipe, there are thousands of ways. Today's cuisine is a meeting place between those who want to tell stories and those who are willing to listen. It's not uncommon to buy a cookbook and never cook anything from it, and that's okay. "I buy cookbooks to find cooking ideas, to read interesting stories and learn kitchen techniques rather than to find recipes, which can be found on Google," - culture writer Nilanjana Roy wrote in Financial Times magazine in May 2023. In an article on LitHub, author Joshua Raff also pointed out the differences between cookbooks before and after the explosion of online recipes and the trend towards convenience. Specifically, according to this culinary writer, in the past, classic books such as French Country Cooking (1951), Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961) or The Classic Italian Cookbook (1973) provided basic knowledge for many generations of chefs from amateur to professional with French and Italian recipes, along with instructions and some basic cultural context. But they had no pictures, no personal stories about cooking or enjoying a meal with friends and family, and no broader cultural commentary. This is very different from today's cookbooks, which, in addition to recipes and instructions on techniques and ingredients, often contain a story that illuminates a recipe, a culture, or a setting, and are received by readers as personal essays, travel books, or life books. Matt Sartwell, manager of New York culinary bookstore Kitchen Arts and Letters, agrees: cookbook buyers want something more than just a set of recipes; and that "something" is the author's own voice. Similarly, Michael Lui Ka, former editor of Eat and Travel Weekly and owner of Hong Kong-based food bookstore Word by Word, has followed her own philosophy of combining science, creativity and cooking in her collection of 365 Chinese soup recipes. “I wanted to introduce a soup every day, building the collection based on the seasons and traditional Chinese solar terms, which can affect our metabolism and bodily functions,” she told the South China Morning Post. Cookbooks are also fun and spark creativity. “It’s not just about reproducing recipes, but also about thinking about how chefs create them,” Peter Find, head chef of the German restaurant Heimat by Peter Find in Hong Kong, told the South China Morning Post. According to him, the recipes in the book help readers understand the mind of the chef, even if they don’t know if they can cook them. Besides, one reason why many readers turn to cookbooks is to get clear instructions from experts, when the huge amount of information on the internet can make people dizzy and not know which way to cook properly. Moreover, book buyers also want to know what chefs think, how to cook to become famous in the industry. Not to mention, a cookbook written by a famous chef will be a valuable gift or souvenir for themselves or loved ones who love cooking, just like the way people are proud to own a copy of The Margaret Fulton Cookbook from 1969. Helen Le, or Le Ha Huyen, currently lives and works in Da Nang . She is the owner of the YouTube channel Helen's Recipes (more than 639,000 followers) and the author of Vietnamese Food with Helen's Recipes (2014), Vietnamese Food with Helen (2015), Simply Pho (English published in 2017, Chinese published in 2019), Xi Xa Xi Xup (2017); Vegetarian Kitchen (2021) and most recently Vegan Vietnamese (2023). * You are already famous for your video recipes, why do you still want to publish a book, when people can easily learn from your YouTube? - It was the video viewers who first asked me to make a book because they wanted to hold a tangible work in their hands - where readers can find stories, and connect with culinary culture in a deeper way. That was the motivation for me to start making books, even though I was not really good at writing. After self-publishing my first book, I realized that book publishing has a different value that videos cannot completely replace. Books provide a personal experience, helping readers focus, explore each page slowly, thoughtfully and contemplatively. It also creates a sense of nostalgia and tradition - like the way we used to look for recipes in our mother or grandmother's notebooks. In addition, books can be stored and referenced at any time, whether there is Internet or not. For me, book publishing is a way to summarize and preserve culinary experiences and knowledge, creating a more lasting and sustainable value than the fast-paced digital life of online content. In a few decades, my videos may disappear due to platform changes, but my books will still be on the shelves of library systems around the world. That's special, isn't it? * The cookbook market is heavily influenced by online media, what factors help you still confidently choose to publish books? - I believe that cookbooks have a special appeal and values that cannot be easily replaced by online content, such as reliability and systematicity. Cookbooks, especially those from famous chefs or culinary influencers, often provide truly high-quality, time-tested recipes. Readers can trust that the recipes are accurate and produce the desired results. Meanwhile, cooking from recipes found online can be a bit hit-or-miss. A cookbook can provide a systematic approach, helping beginners improve gradually or delve deeper into a particular cuisine. In addition, a book creates a real-life experience that online tools cannot provide. Flipping through a book, taking notes directly on the book, or placing it in the kitchen is always an enjoyable experience for those who love to cook. It is like a personal property that can be kept for generations. When reading a book, readers have the space and time to contemplate and study it more carefully. Meanwhile, with online content, people tend to skim quickly and can be distracted by many other factors. Many authors in the world today follow the path of writing cookbooks not only to share recipes but also other values. Is this view true for you and your books? I also believe that a cookbook is not simply a collection of recipes, but also a cultural and emotional journey. In each recipe, I always try to share stories about the origin of the dish, personal memories, or characteristics of history and family traditions. I hope that through the books, readers will not only learn how to cook but also understand more deeply about Vietnamese culture, feel the love and passion that I have for cuisine. The combination of recipes and stories helps create a comprehensive experience, inspiring readers to explore and appreciate more traditional culinary values. In addition, I also pay attention to the aesthetics of the food presentation and book design. Beautiful pictures and harmonious layout not only attract readers but also inspire cooking. I hope that through these efforts, my books can bring value beyond cooking, becoming a bridge between people and culture, between the past and the present. Thank you! Unable to resist the temptation of eating food on screen, Tran Ba Nhan decided to start cooking the delicious dishes he saw on screen. Nhan is the owner of the TikTok channel let Nhan cook (@nhanxphanh) with more than 419,600 followers after nearly 2 years. Although he has never studied cooking, the 26-year-old TikToker attracts viewers with a special series "In the Movies" - with nearly 60 videos recreating dishes that have appeared on screen, from live-action movies to animations. These include ramdon noodles in Parasite, ratatouille in the animated film of the same name, shoyu ramen in Detective Conan, then scallion oil noodles in Everything Everywhere All at Once, or even traditional tacos in the blockbuster Avengers: Endgame... Each video is meticulously filmed, leading viewers into the kitchen where Nhan introduces the food, the movie, the ingredients, and the method of making it meticulously. Working in logistics in Ho Chi Minh City, Nhan said that when watching movies, he always pays special attention to cooking scenes or dishes appearing, and at the same time wants to try those dishes. "I saw that no one had made dishes in movies with specific details on how to prepare them, or information about the ingredients to introduce to everyone, so I started to try making them in my own style," Nhan said. From the first videos that were still reserved, by mid-2023, the videos on Nhan's channel began to be well received by the audience and they started asking him to cook more dishes. "At first, I would choose dishes in good, famous movies or movies that I liked, gradually when people watched and had their own requests for specific dishes in a certain movie, I would choose dishes that were feasible in terms of recipe and form to make," he said. After choosing a dish, Nhan researches information, ingredients, and how to make it. "More importantly, when recreating dishes in movies, viewers will like scenes that 'imitate' the camera angles and actions in the movie, so I also research to put it in the video." Nhan said that most of the dishes in movies do not have specific recipes, only ingredients. Sometimes some ingredients are not mentioned, so he has to watch them over and over again, look at the pictures, and guess based on related information. Usually, dishes in movies will be varied, creative, or combined with real-life dishes. On the other hand, there are also dishes that Nhan has successfully made that are "delicious beyond words", such as ichiraku ramen from Naruto or Karaage Roll from Food Wars. "I hope one day I can open a small restaurant serving dishes from the movie so that people who love the movie or are curious to try it will have the opportunity to experience it," the TikToker added. Novels can also be a source of culinary inspiration. Food plays an important role as a literary device, conveying mood and adding depth to characters and their experiences. By trying to prepare dishes described or even just mentioned in their favorite books, readers will discover a rich and creative culinary world. And in a way, they will "live" in the stories and characters they love. Food in novels is also a symbol of the character's culture, psychology and living conditions. Food in The Great Gatsby (F. Scott Fitzgerald) is often associated with the luxury and wealth of the upper class in the 1920s. The lavish parties at Gatsby's mansion are a central part of the story, with tables overflowing with food and wine, representing the ostentation and emptiness of a wealthy life. Food is not just a material satisfaction but also a symbol of vanity and pretense. In Little Women (Louisa May Alcott), food is not just a material need but a symbol of care, love and kindness – the Christmas breakfast the March sisters bring to Miss Hummel and her sick children, the sumptuous feast of rich turkey, the melting plum pudding – the main gift they receive for their kindness from their neighbor Mr. Laurence. Pizza is not just a dish but also a symbol of enjoyment, freedom, connection with the world through the flavors and cultures of each place she visits and how Elizabeth learns to love herself through simple but meaningful experiences when she escapes from boring salads to keep her slim body and confined life in America. By recognizing, preparing, and enjoying the dishes from the novels, readers can engage with the stories in a new and meaningful way. Reflecting on these meals creates a sensory and taste connection with the stories, allowing readers to experience a small part of the characters' lives. The simplicity of the dishes in Haruki Murakami's stories makes them accessible to everyone, regardless of cooking skills. However, there are also more elaborate dishes and sumptuous feasts, which make food-loving readers collect and experiment. From there, articles "recreating" recipes or cookbooks inspired by novels were born. Inspired by his four seasons in England, his childhood in Australia, his family meals and his culinary memories, Young has created more than 100 recipes from his favourite stories, from Edmund's Turkish Delight in CS Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, pancakes in Pippi Longstocking (Astrid Lindgren) to apple pie in Edith Nesbit's The Railway Children. The Guardian quotes Young's three-meal recipe from the book: a simple breakfast of miso soup from Norwegian Wood, a lunch of spankopita, a Greek pancake made from walnuts, butter, honey, spinach and cheese, inspired by Jeffrey Eugenides' Hermaphrodite, and a dinner of steak and onions from Graham Greene's The End of the Affair. There's also a dinner party with "a wonderful, chewy, hot marmalade roll" in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (The Chronicles of Narnia Part 2). Karen Pierce, a food writer in Toronto (Canada), has been diligently exploring the recipes hidden throughout the works of detective queen Agatha Christie. After testing and synthesizing 66 recipes from her favorite author's stories, Pierce published them in the book Recipes for Murder: 66 Dishes That Celebrate the Mysteries of Agatha Christie last August. The dishes range from the 1920s to the 1960s, deliberately named to clearly show which story they were inspired by, such as fish and chips "Fish and Chips at the Seven Dials Club" (Seven Dials), lemonade "Lemon squash on the Karnak" (Murder on the Nile).

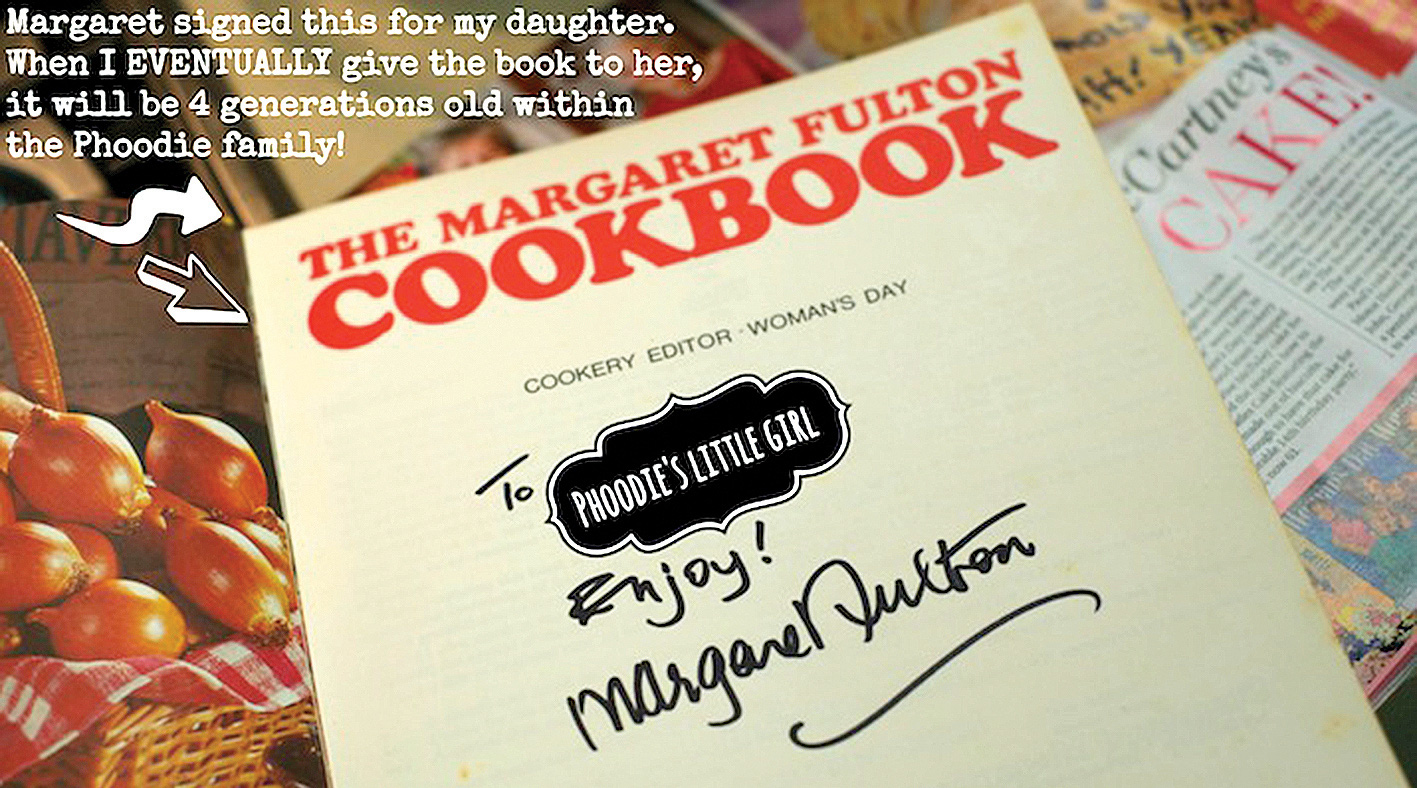

Australian food blogger Phoodie shared a photo of a signed copy of The Margaret Fulton. Phoodie will be giving the book to her daughter, thus passing it down to the fourth generation of her family.

The book Recipes for murder and the chocolate cake with the impressive name "delicious death". Photo: NDR

Tuoitre.vn

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/mo-sach-nau-an-lan-theo-dau-su-20241105174430082.htm

Comment (0)