|

German Economy Minister Habeck's industrial strategy has the support of industry and unions, but lacks consensus among coalition parties. (Source: DPA) |

Germany, Europe's largest economy, is facing recession as high energy costs weigh on industrial companies. German Economy Minister Robert Habeck, of the Green Party, wants to change this but is facing opposition.

Business confidence in Germany is at rock bottom as the country reported the lowest economic growth among the Group of Seven (G7) leading industrialized nations for the first half of 2023. While countries like the US and even France are growing, Europe's leading economy is forecast to shrink by 0.4% this year.

A survey conducted by the German Employers' Association (BDA) last October showed that 82% of business owners surveyed expressed great concern about the state of the economy, with about 88% saying that the government had no plan to deal with the crisis.

Greens Minister Robert Habeck is facing a host of major issues, including geopolitical challenges from the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the situation in the Middle East and China's rise in Asia.

Add to that Berlin's costly transition to a carbon-neutral economy, slow pace of digitalization and a shortage of skilled workers.

For decades, a strong industrial sector - which accounts for around 23% of gross domestic product (GDP) - has been the backbone of the German economy, alongside thousands of small and medium-sized enterprises.

Industry rescue plan

In mid-October, Minister Habeck proposed the Industrial Strategy – a 60-page blueprint of urgently needed measures and numerous state subsidies for the coming years.

With this plan, Mr Habeck is following in the footsteps of US President Joe Biden, who is currently spending a total of $740 billion (€700 billion) to invest in greener industries in the world's No. 1 economy. Dubbed the Degrowth Act, Mr Biden's plan includes large tax incentives in addition to direct subsidies.

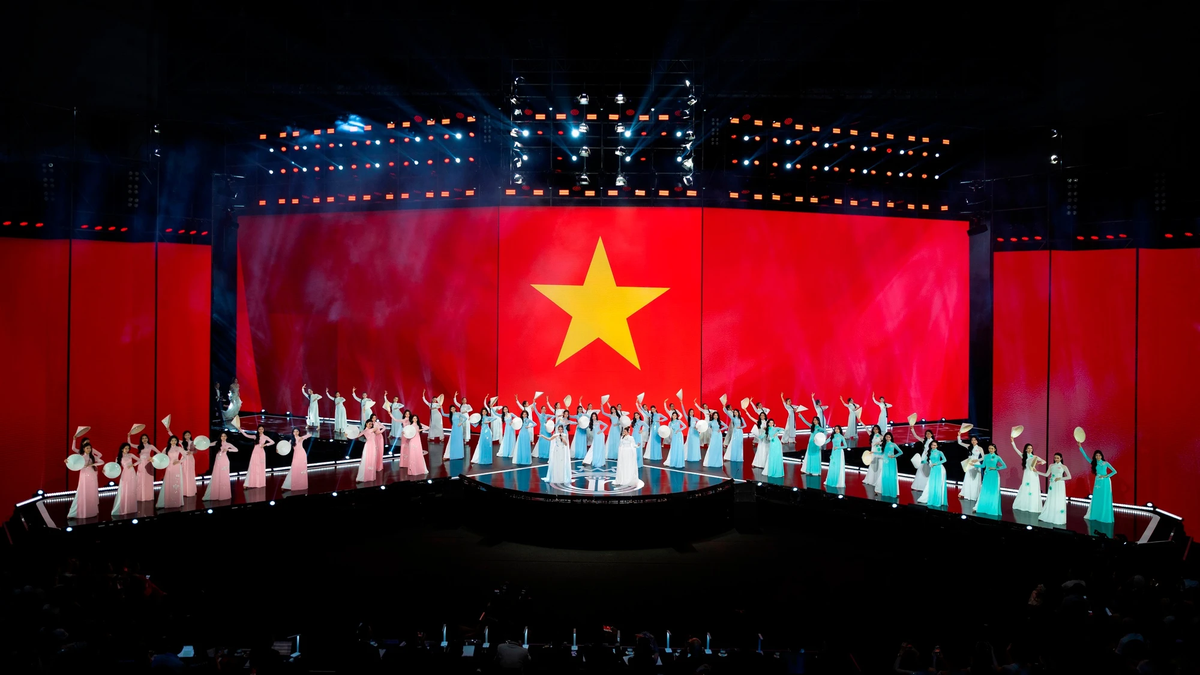

Minister Habeck's strategy has been welcomed by both industry leaders and union leaders, who have long called for state support in difficult times.

However, the plan has not gone down well in the German government, which is made up of three different parties with different economic policies. While Mr Habeck's Greens are known for their interventionist approach to the state, the Free Democrats are traditionally against state interference in business, and the Social Democrats are reluctant to endorse anything that might harm working-class voters.

But what most upset Mr Habeck's coalition partners was the timing of the strategy and his failure to discuss it with them before making his proposal public.

Limiting electricity costs for industry

A key element of the new industrial strategy is heavy subsidies for electricity prices in a number of industries that have suffered heavily from high energy prices following Russia's special military campaign in Ukraine.

Germany's two decades of remarkable economic success have been fueled by cheap Russian energy supplies. Companies in the Western European country have turned this into a competitive advantage in the market. Germany has been a world export champion for many years, and "Made in Germany" products have become a global standard for quality.

Without cheap Russian gas, German industrial companies now have to rely on more expensive liquefied natural gas (LNG). As a result, electricity prices in the country have skyrocketed to the highest in the world due to the country's dependence on expensive gas to generate electricity.

Empty treasury

Under his proposed new strategy, Mr. Habeck calls for electricity subsidies for industry of 6 euro cents ($0.063) per kilowatt hour. By comparison, Germans still pay about 40 euro cents per kilowatt hour of retail electricity, while industries in the United States or France enjoy prices as low as 4 euro cents.

Industrial electricity prices are also being viewed with caution within Habeck’s Green Party. Making energy cheaper goes against green climate ideology and efforts to curb environmentally unfriendly manufacturing. They seem to have reluctantly agreed to the plan after realising that Germans are increasingly overwhelmed by the looming cost-of-living crisis.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz's Social Democrats have largely ignored price subsidies for industry, fearing that declining production and job losses could fuel political factions in Germany that are making big gains in the polls.

But Chancellor Scholz remains unconvinced that low prices will increase demand and lead to shortages that will drive prices up again. State subsidies, he argues, could undermine the industry’s efforts to ensure energy security and move towards carbon neutrality.

However, the most vocal opposition to Habeck's plan comes from the Free Democrats (FDP). Finance Minister Christian Lindner, a member of the FDP, is a staunch defender of Germany's debt relief plan. This means the government is constitutionally bound to overspend and significantly increase the country's debt burden. That is why Lindner refused to allocate €30 billion until 2030 in next year's budget.

|

Energy-intensive industries such as chemicals have thrived on cheap gas, but are struggling to maintain their competitive edge. (Source: DPA) |

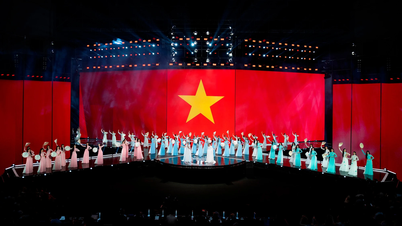

Core industries at risk of disappearing

Amid the government's failure to find common ground, both industry leaders and unions have warned of a "loss of energy-intensive manufacturing" if the industrial energy subsidy plan is not implemented.

Their concerns were echoed by Mr Habeck at a recent industry conference in Berlin, who said Germany's industrial supply chain was “very intact from raw materials to final production”.

“Of course, we could go back to making everything by hand, but then we would weaken Germany,” he said.

And in fact, the Federation of German Industries (BDI) is constantly warning that energy-intensive businesses could be forced to relocate abroad if nothing changes. “If there is no longer a chemical industry in Germany, it would be an illusion to think that the transformation of chemical plants will continue,” BDI President Siegfrid Russwurm told the conference.

And Jürgen Kerner, vice chairman of the trade union of Germany’s largest metal group IG Metall, added that businesses, especially mid-sized family-owned companies, now have “no prospect of continuing their business”. There is great uncertainty, he said, as “aluminium smelters are shutting down, foundries and forges are losing orders”.

IG Metall's subsidiaries are increasingly reporting insolvency, planning "layoffs and business closures".

How to finance the plan?

With Germany's state coffers nearly empty amid a series of costly and complex crises, political consensus on how to finance subsidized industrial electricity prices seems unlikely.

The country's economy minister is planning to increase national debt to fund it, but added that this could only be implemented after a general election in 2025.

Despite the pressure on German industry, lobbyists like Siegfried Russwurm of the BDI are against adding more government debt. “I think we will have to set priorities in the state budget,” he said. “We need to resolve the conflict between what is possible and what is desirable but beyond our means.”

Habeck is still hoping to convince his coalition partners, the Social Democrats and the Free Democrats, of a plan to rescue Germany's industrial base with state support. The crunch point will be the 2024 budget talks starting in November, when there are "50-50" odds that industrial electricity prices will be unified.

Source

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman works with leaders of Can Tho city, Hau Giang and Soc Trang provinces](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/c40b0aead4bd43c8ba1f48d2de40720e)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs the fourth meeting of the Steering Committee for Eliminating Temporary and Dilapidated Houses](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/e64c18fd03984747ba213053c9bf5c5a)

![[Photo] Discover the beautiful scenery of Wulingyuan in Zhangjiajie, China](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/1207318fb0b0467fb0f5ea4869da5517)

![[Photo] The moment Harry Kane lifted the Bundesliga trophy for the first time](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/11/68e4a433c079457b9e84dd4b9fa694fe)

Comment (0)