|

| Eastern European countries have built fences to keep migrants out. However, they now realize that their economies depend on foreign labor. (Source: AP) |

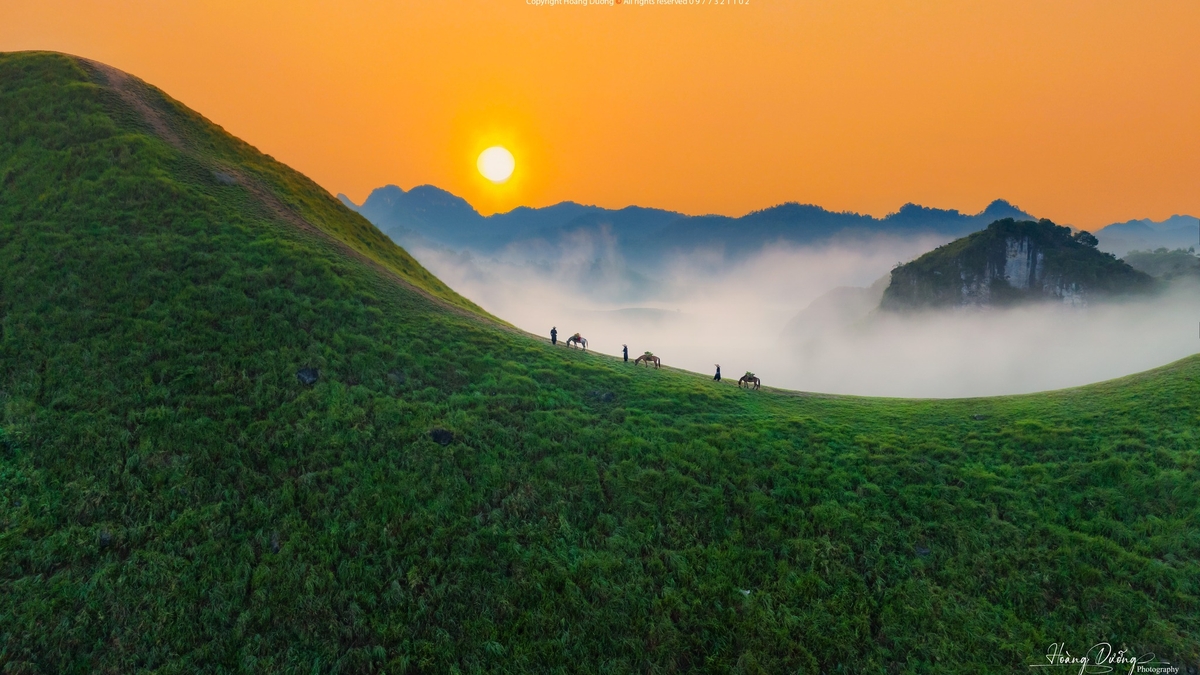

“Three years ago I would never have imagined that I would be in Warsaw drinking Polish beer,” said Shourya Singh, a risk manager from Varanasi in northeastern India who works for Ernst & Young (EY), a professional auditing services firm in the Polish capital.

Shourya revealed that he was recruited by an international HR firm through LinkedIn and worked on a contract basis at Dutch bank ING, before he joined EY.

Shourya's story is not uncommon.

|

| Shourya Singh says he has made more Indian friends in Poland than in his own country. (Source: Privat) |

Abraham Ingo, a 20-year-old from Namibia, currently works as a credit risk management model developer for a large bank in Warsaw. Abraham said that coming to Poland opened up a new world for him.

“My experience working here has been truly amazing. The company has a great work culture, diverse workforce and effective management. Living in Poland has helped me grow and given me a foundation to contribute to my home country of Namibia in the long term,” said Abraham.

Central and Eastern Europe change

Poland and the other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries have undergone dramatic changes. In the 19 years since joining the EU, many countries have developed at breakneck speed, moving from emerging to developed market status.

This of course brings serious investment to the European economy, but at the same time it also creates a number of challenges such as an aging population, labor shortages, rapidly rising wages and an increased need for immigrant labor.

Among them, industry, healthcare , transportation and information technology are the economic sectors with the most serious labor shortages.

Demographic issues say a lot.

Europe's labor shortage is a result of demographic changes, mainly from population aging and migration, coupled with unprecedented economic growth.

Most countries in the region have experienced population decline over the past 15 years. According to data from the European Employment Service (EURES), a network that facilitates the free movement of workers in the EU, CEE countries also experienced this phenomenon between 2010 and 2021.

|

| Western businesses in Eastern Europe are finding it increasingly difficult to find skilled workers. |

Migration and low fertility rates are expected to cause the working-age population (20-64 years) in CEE countries to decline by around 30% by 2050.

The dependency ratio – the ratio of non-working-age people to working-age people – has also increased over the past decade. According to Poland’s social security office ZUS, for the dependency ratio to decrease, the number of working-age foreigners would have to increase by 200,000 to 400,000 annually in Poland alone.

Green economic transition reshapes labor markets

In addition to demographic issues, “the context of economies undergoing green and digital transformation should also be taken into consideration,” said Nadia Kurtieva, an expert at Poland’s Lewiatan Federation.

“These two parallel trends are reshaping the labor market by creating new career opportunities, which in turn will influence the skills and expertise that organizations require, but there will be a significant shortage of skilled workers to meet the demand,” Mr. Kurtieva added.

Several CEE countries also face severe shortages in their domestic markets due to the emigration of certain occupations that are already in short supply.

According to the World Bank, Slovenia had the highest net migration among CEE countries, reaching 4,568 people in 2021. Net migration is an annual rate that takes into account both immigration and emigration. Romania had the lowest at 12,724 people.

The situation has changed following the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which has had significant consequences for the labor supply in the region. Currently, Poland hosts the highest number of refugees from Ukraine, estimated at around 1 million.

Wave of foreign workers

In 2021, the Romanian government approved a policy to increase the number of visas that can be issued to foreign workers for 2022 to 100,000. Foreigners account for only 1.1% of the country's workforce.

The Romanian government said this year it was ready to take in 100,000 non-EU workers. After Bulgaria, Romania has opened its doors to skilled workers from Bangladesh, for jobs in agriculture, construction and services.

There are more than 4.7 million people working in Hungary and according to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH), 85,000 of them are foreigners.

However, the domestic labor market will soon need another 500,000 workers, according to Economic Development Minister Marton Nagy. Hungary has expanded the list of non-EU countries that are allowed to recruit workers, although it will tighten the terms under which they can stay. The government says there are currently at least 3,000 positions available for skilled Filipino workers in Hungary.

The same is true in Poland. Tomasz Danel, consul at the Polish Embassy in Manila, told The Freeman of the Philippines that Poland is currently short of construction workers, welders, drivers and many other low-skilled occupations. “Poland is becoming increasingly popular among Filipinos as a work destination and the number is increasing every year,” Danel said.

According to research conducted by the Polish Economic Institute and BGK (a Polish development bank), four out of ten companies in Poland employ foreigners who are not EU citizens.

|

| Migrant workers in Eastern Europe and the story of who needs whom more. |

A real-life example of this phenomenon is the emergence of “container towns,” a project to provide housing for foreign workers, mainly from Asia, at a large petrochemical facility being built by the Orlen energy company near Plock in central Poland. About 6,000 foreign workers from Türkiye, India, Pakistan and South Korea are expected to live and work there. Recreational activities are also included in the project, including the construction of a cricket field.

According to official government data, as of December 2022, there were an estimated 1 million foreign workers in the Czech Republic, accounting for 15% of the adult workforce. Less than half of them came from other European countries.

Czech companies lose between 30,000 and 50,000 workers each year due to retirement, said Jan Rafaj, vice president of the Czech Industry Association. “The domestic labor market cannot solve this problem without foreigners,” he said.

Integration is still a problem in most Central and Eastern European countries. However, that does not bother Shouya. “I do not find many difficulties in my career, except for the language. But of course, Google Translate helps."

Source

Comment (0)