Looking at countries that are new to high-speed rail, we can see some commonalities. Typically, new urban areas are planned around train stations, aiming to create new development centers and promote regional economic growth.

Let's take a look at lessons from planning high-speed rail stations in Europe, Japan, or neighboring countries such as Laos and China. Most high-speed rail stations in Europe and Japan are seamlessly integrated with existing public transport systems, located in the center of large cities to contribute to urban regeneration. A typical example is Shinjuku Station in Tokyo. With a huge passenger volume of nearly 4 million people per day, Shinjuku Station is designed to optimize multi-modal connections, from subways, buses to other railway lines, while also creating momentum for the development of commercial services and surrounding amenities. However, this model focuses heavily on renovating existing urban areas, reflecting the needs of highly developed economies where the population is concentrated in urban areas. In contrast, for emerging economies in Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, the basic priorities in planning railway stations will be almost completely different. Although urbanization has been accelerated over the past 30 years, the urbanization rate in countries in the region is still quite low compared to Japan (92%); South Korea (81%); or the European Union (75%). In Vietnam, the current rate is only about 40%; lower than large Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand (54%); Indonesia (58%); or the Philippines (48%); but higher than Laos (37%) and Cambodia (26%). However, urbanization is taking place very rapidly throughout the region, reflecting the dynamism of ASEAN in general and Vietnam in particular. This means that sustainable railway projects need to meet the needs of both urban and rural areas, reflecting the population structure of the country. In particular, it is possible to support the rapid urbanization process by expanding city connections to new areas, reducing pressure on the existing inner city; as well as connecting industrial zones, facilitating inter-regional trade, and supporting economic growth in suburban areas by having railway lines that allow people to conveniently commute to work in major cities. Laos' experience Railway stations in Laos, China, and Indonesia are all planned away from the city center. In Laos, Vientiane currently has two main passenger stations: Vientiane station, located at the starting point of the Boten-Vientiane high-speed railway line, and Khamsavath station, located at the end of the railway line connecting to Thailand. Both stations are located at least 10 km from the city center, and there is currently no urban railway, so passengers can take taxis or use shuttle bus services from the city center. Currently, the area around the stations along the Boten-Vientiane line is not very developed. However, in three key urban areas – Vientiane, Vang Vieng, and Luang Prabang – there are plans to develop new urban areas around the train stations. Vientiane is focusing on developing the train station into a multimodal transport hub with commercial, office, and residential facilities, with links to the southern bus station, which is 10 minutes away, and the international airport. In Vang Vieng, Chinese enterprises have invested in hotels and restaurants around the train station to develop the city’s eco -tourism potential. The Lao-China Railway Company (LCRC), the investor, builder, and operator of the Boten-Vientiane railway line under the BOT model, is also responsible for developing the areas around the station. This allows the joint venture to maximize the value of the project through land sales, site leasing, and planning of commercial and industrial areas, thereby generating revenue and promoting the development of surrounding areas. Thus, it is understandable why Thuong Tin station in Hanoi and Thu Thiem station in Ho Chi Minh City are planned out of the center. It is important to have a specific strategy to develop the areas around the station, to maximize the economic spillover effect and create new centers. For example, real estate prices can increase by 5-20% around the station, with the most significant increase within 2km of the station.

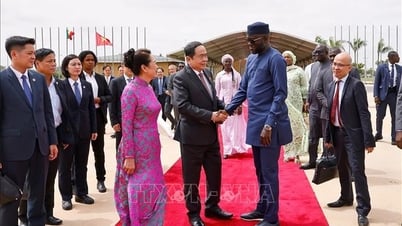

Vientiane Railway Station, Laos. Photo: Laos Railway

Some other lessons learned New stations can encourage businesses to relocate to locations around the stations and create local jobs. For example, the UK’s Crossrail project has helped to shift 23,000 jobs away from major cities, and is forecast to boost GDP by £42 billion nationwide. In the US, a study in Massachusetts estimated that nearly 2 million square metres of new urban development could be created around 13 stations along suburban rail lines, creating more than 230,000 new jobs. However, this does not mean that high-speed rail should bypass inner-city areas entirely. A University of Tokyo study for the Mumbai-Ahmedabad high-speed rail project identified that each city along the planned economic corridor would have different economic development needs, and so the location of high-speed rail stations would be based on those needs. There will be several major socio-economic factors driving the demand for high-speed rail; such as (1) high concentration of corporate/business headquarters; (2) high concentration of industrial production; (3) reduction of pressure on the inner city by expanding the city. For example, rapidly growing cities like Surat aim to develop polycentrically and reduce pressure on the inner city, and so have planned to locate high-speed rail stations on the outskirts, completely outside the city. Meanwhile, Mumbai, India's most populous city and economic engine, will build three high-speed rail stations, one of which will be located right in the center to maximize connectivity with the country's financial center; as well as reduce severe congestion in the city. Two other stations are planned completely outside the city, with the aim of developing new growth poles for services and industry. Potential for regional economic restructuring In addition, a trend that needs to be noted when developing the railway network, especially in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, is the possibility that new railway lines will restructure the regional economic system, making the cities/towns located on the outskirts increasingly dependent on a central city. Provinces and cities along the new railway lines can take advantage of the opportunity to develop high-value-added industries and services to serve the needs of the two large cities. However, to limit the situation of over-concentration in large cities, it is necessary to have a synchronous development plan for central cities and surrounding areas, creating new growth poles. A study by Zhejiang University (published 2023) shows that opening high-speed rail connections significantly reduces the transportation costs of industrial companies in district areas, facilitating the reallocation of production chains. The study also found a double effect: this increases the attractiveness of urban centers, causing many businesses to tend to move to large cities to take advantage of developed infrastructure and larger consumer markets. To solve the problem, a balanced policy framework is needed to both encourage the development of rural areas and support large urban areas to avoid overcrowding. It is possible to identify different city centers, assigning each center a separate function (specific industrial sectors, finance, administration, etc.). It is also important that the planning process needs to identify the needs of each urban area, and develop stations based on this model. For Vietnam, the balance between connecting people and workers to industrial zones and suburbs; and reducing congestion in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City will be very important. The next step will be to determine that a city with the population, economic, and social scale of these two key urban areas needs at least 2-4 major train stations, connected to high-speed rail, to operate effectively.Vietnamnet.vn

Source: https://vietnamnet.vn/mot-vai-kinh-nghiem-quoc-te-ve-quy-hoach-ga-duong-sat-cao-toc-2334127.html

![[Photo] Cat Ba - Green island paradise](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F04%2F1764821844074_ndo_br_1-dcbthienduongxanh638-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)