Dear, trust people

“…My house is big and full of jars,/ I am the best hunter in the land/ And my fields are the most beautiful/ The rooster will make a deal for us/ And I will take you into the forest/ Anyone who wants to stop me/ Will be hit by my spear twenty times”.

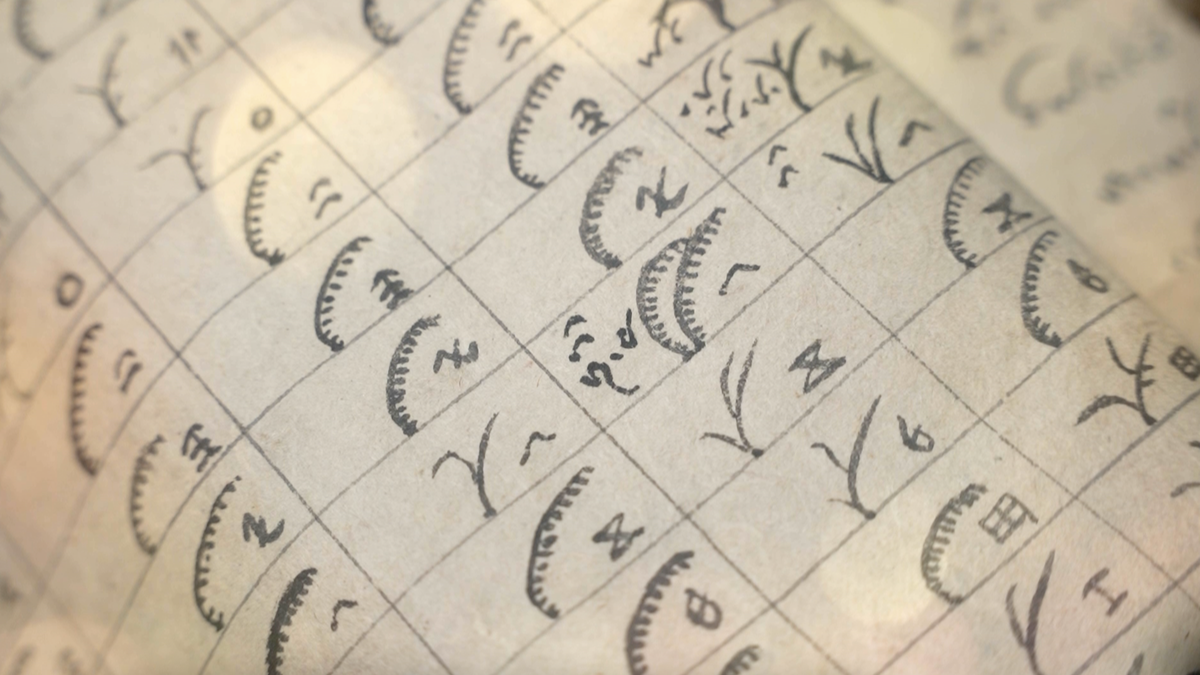

The song praising the jars (jo/cho) of the Co Tu people, cited by researcher Tran Ky Phuong from documents of Le Pichon (magazine Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hue published in 1938), revealed their “full of jars” fortune. But the path that the jars must “go” through, from the lowlands to the highlands, before being neatly and solemnly arranged inside the Co Tu people’s house, is “hidden”. Later, jars and ceramic items were more present in the community activities of the ethnic minorities in the highlands.

To get beautiful jars, the Co Tu people have to go to the lowland markets to exchange with close/sworn (pr'đì noh) Kinh people. In the work "Champa Art - Research on Temple and Tower Architecture and Sculpture" (The Gioi Publishing House 2021), researcher Tran Ky Phuong said that each Co Tu family has a need to collect many jars, so they have their own familiar trading relationships considered as friends/brothers to regularly exchange these products.

Communities in other highland areas also have similar needs. But first, they must have equivalent products to exchange, or have money. In the lullaby of a Ca Dong mother in Quang Nam collected by researcher Nguyen Van Bon (Tan Hoai Da Vu), there is a step of earning money to buy goods and gifts:

“…Don’t cry too much/ Your mouth hurts/ Don’t cry too much/ Your father went to cut cinnamon/ To sell in Tra My To buy things for you”. (Nguyen Van Bon, Quang Nam – Da Nang Folk Literature, volume 3).

Researcher Tran Ky Phuong’s description of the commodity exchange network in the lowlands and the highlands shows that in the past, the Co Tu people carried their goods to big markets such as Ha Tan, Ai Nghia, Tuy Loan… to exchange for jars and gongs. On the contrary, Kinh people often brought their goods to distant villages to sell and exchange. Usually, the marketing of high-end goods such as precious jars was introduced by intermediary “brokers”.

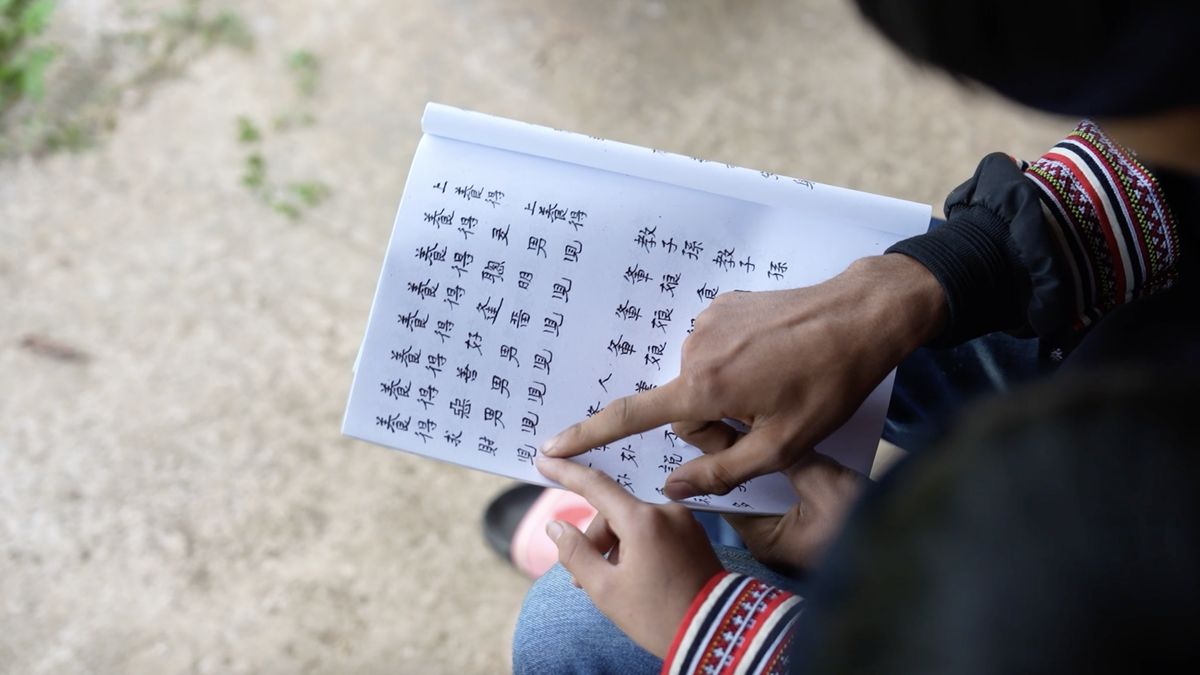

Of course, they are trustworthy people. “Because jars are high-end goods, to exchange jars, one usually has to go through an intermediary. They are people who can communicate in the Co Tu or Kinh languages. The Co Tu call the intermediary “ador luot dol”, which means the person who sells. The intermediary can be either Kinh or Co Tu. When they know that someone wants to buy a jar, they will directly guide the buyer to meet the seller to see the jar, then the two people discuss the exchange with each other” (Tran Ky Phuong, ibid).

"Transporter" in the jungle

On the Cai River upstream of the Vu Gia River, about 30km from Ben Gieng, there is a large sandbank named “Bai Trau” - once a bustling market, now located in Dai Dong Commune (Dai Loc). Witnesses said that people from the lowlands brought common goods such as fish sauce, salt, mats, fabrics, etc. here to exchange for betel leaves, honey, and chay tree bark (to chew betel). As for the Co Tu people, if they want to have more valuable goods such as jars, gongs, bronze pots, bronze trays, etc., they have to carry their goods all the way to the midland markets of Ha Tan, Ha Nha, and Ai Nghia to exchange or buy.

Over time, the Kinh-Thuong relationship became closer, especially through trade routes. That is why, from the beginning of the 20th century, the French colonialists established An Diem station (the border area between the Dai Loc midland and the Hien-Giang highland) to use the trick of expanding free trade exchanges, plotting to lure ethnic minorities in the mountains. More deeply, the enemy wanted to reduce the influence of Kinh traders at the source of the Bung and Cai rivers.

By the mid-1950s, some Kinh traders were respectfully called “father” or “uncle” by the Co Tu people due to their close relationship. Such as “father Lac”, “father Bon” in Ai Nghia market; “father Suong”, “father Lau”, “father Truong” in Ha Tan and Ha Nha markets; “uncle De” in Tuy Loan market. Also according to the research work of author Tran Ky Phuong (mentioned), the person called “uncle De” in Tuy Loan market had the full name Mai De, born in 1913.

In April 1975, when they heard that he was summoned to work with the revolutionary government (because he was a security officer of the old regime), a group of Co Tu people in the Central Man region came down to ask for help. They argued that, during the anti-American period, without the help of "Uncle De", they could not have bought food and medicine to supply revolutionary cadres operating in the region... After that petition, "Uncle De" was released, even worked for a small-scale industrial cooperative in Hoa Vang and continued to buy and sell forest products with the Co Tu people in the Central Man until his death (in 1988).

Sometimes, the “transporters” also face some risks due to conflicts of interest, mainly because of unfair exchange prices. There was a revenge incident in the early 1920s (according to Quach Xan, a veteran revolutionary cadre) against a trader named “Mrs. Tam” at Ha Nha market. But this type of conflict is not common, and most of the “intermediaries” are always honored, trusted, and entrusted. They deserve to be mentioned in the synthesis of Kinh-Thuong relations in Quang region.

Source: https://baoquangnam.vn/ket-nghia-kinh-thuong-tham-lang-nguoi-trung-giang-3145318.html

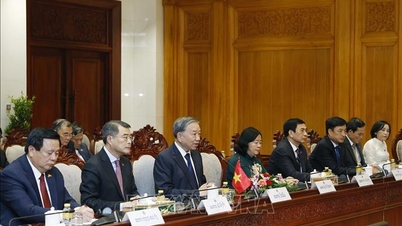

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh receives President of Cuba's Latin American News Agency](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F01%2F1764569497815_dsc-2890-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)