President Ho Chi Minh - the man who fought all his life for the independence, freedom and happiness of the nation and the People was also a very free man in his literary and journalistic creations. Throughout his 50-year writing career, he always expressed himself in a posture of absolute freedom...

Nguyen Ai Quoc - Ho Chi Minh - the founder of the Party and the great leader of the nation, was a man whose writing career began in 1919 with the 8-point Petition sent to the Versailles Conference.

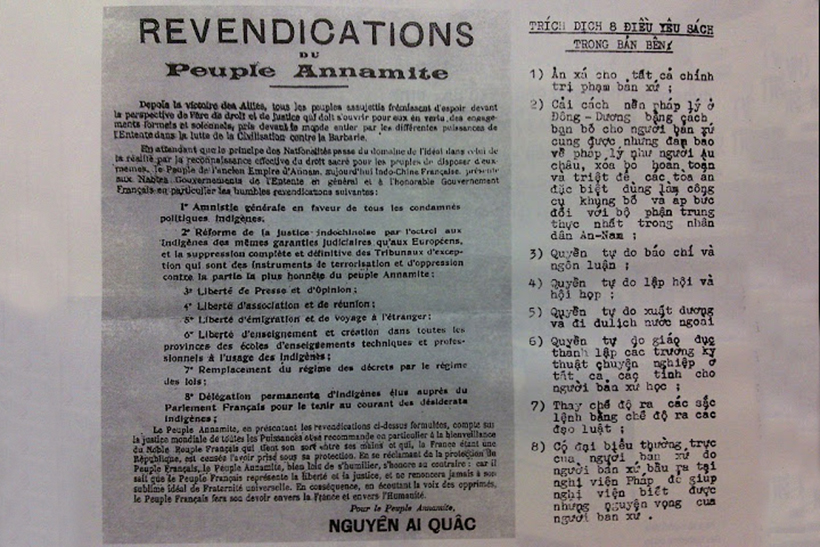

Nguyen Ai Quoc's 8-point petition sent to the Versailles Conference. Photo: Internet

Of those 8 points, 4 demand freedom for the Annamese people:

“3. Freedom of press and speech

4. Freedom of association and assembly

5. Freedom to migrate and travel abroad.

6. Freedom to open and establish in all provinces technical and vocational schools for the natives to study.

These are just a few minimum freedom requirements within a broad category of freedom, linked to independence for the nation and happiness for the People, forming the trio: Independence, Freedom, Happiness, on the basis of Democracy - Republic, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam will be fully realized after the August Revolution - 1945 of which Nguyen Ai Quoc was the founder, leader and first President.

Returning to the 50-year writing career of Nguyen Ai Quoc - Ho Chi Minh, which began in 1919, with two stages: from 1919-1945 and 1945-1969. In the first stage, Nguyen Ai Quoc and then Ho Chi Minh, had a writing career as a revolutionary soldier consciously using the "weapon of voice" to carry out the highest and only historical mission of independence for the nation and freedom for the Vietnamese people. A writing career that began with two types of script: French and Vietnamese, aimed at two subjects: French colonialists and the puppet government of the Southern Dynasty; the suffering people all over the world , including the Annamese people.

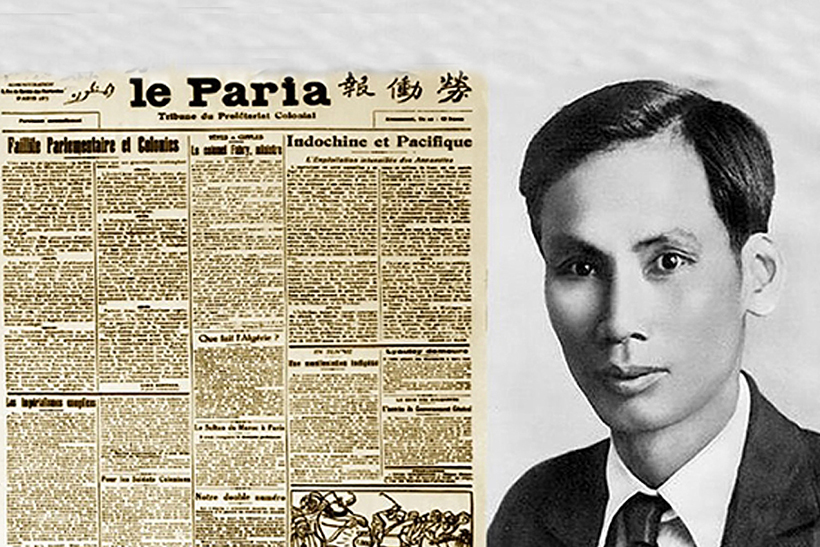

For the enemy, it is a warning; for the native people and the poor around the world, it is an awakening. Warning and awakening - those are the two great goals in the writing career, first in journalism and then in literature of Nguyen Ai Quoc - Ho Chi Minh, from 1919 to 1945. A writing career, starting with The Claim of the Annamese People (1919), the newspaper Le Paria, the play The Bamboo Dragon, short stories and sketches published in French newspapers in Paris in the early 1920s and The Verdict of the French Colonial Regime printed in Paris (1925). Next, The Revolutionary Path (1927) and The Shipwrecked Diary (1931) in Vietnamese were banned and confiscated.

President Ho Chi Minh with the newspaper Le Paria. Photo: Document

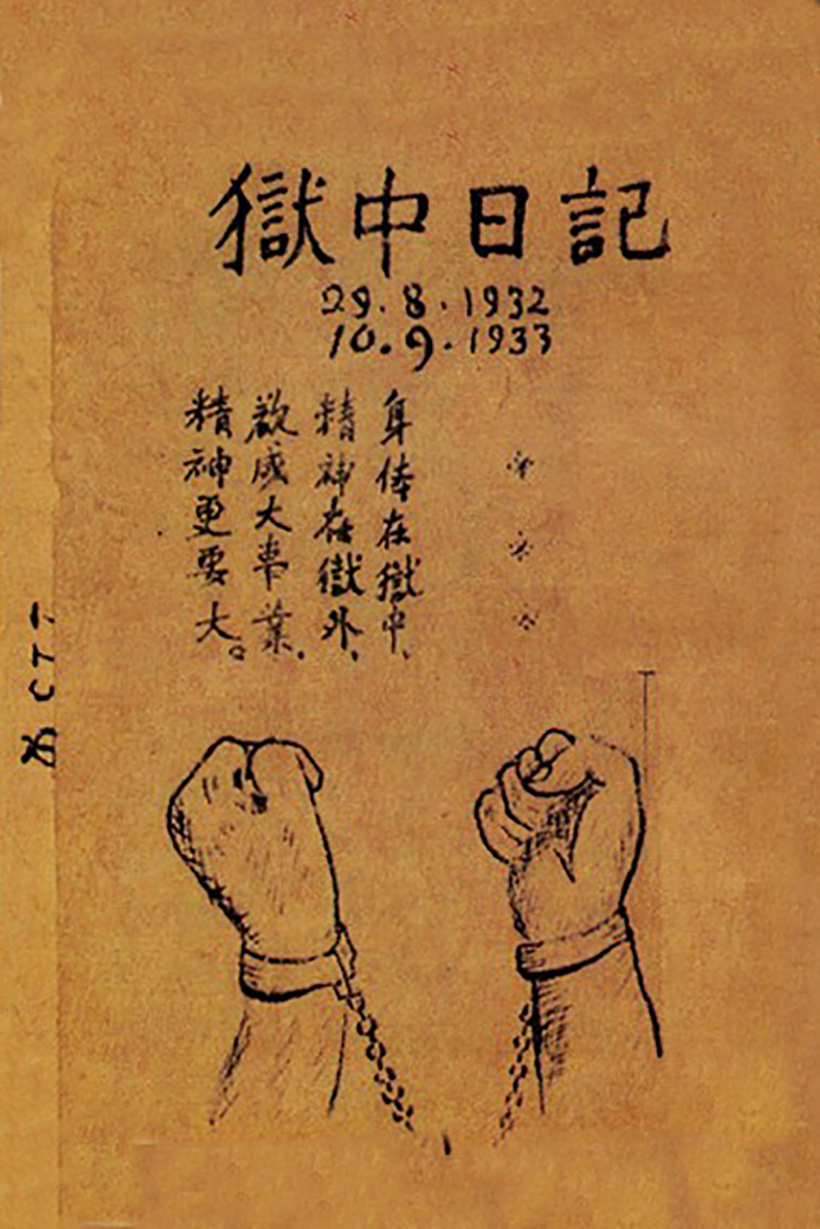

In 1941, Nguyen Ai Quoc returned to the country after 30 years abroad and in the first 4 years of the 1940s, he concentrated on a writing career in many genres such as prose, poetry, opera, and political commentary, of which the most important were over 30 Vietnamese poems called Viet Minh Poetry published in the newspaper Vietnam Doc Lap; opera History of Our Country, 208 verses; Prison Diary - 135 poems in Chinese; many letters calling and urging the nation to fight the French, expel the Japanese, prepare for a general uprising and finally the Declaration of Independence.

More than 25 years before 1945, Nguyen Ai Quoc - Ho Chi Minh left behind a career of writing in three languages: French, Chinese, and Vietnamese, aiming at the highest and only goal of national independence, freedom and happiness for the Vietnamese people. Over 25 years of writing (1919-1945), during 30 years of exile (1911-1941), the great revolutionary and leader of the nation left the Vietnamese people an extremely valuable legacy of journalism and literature, including works that stand at the highest peak of civilizational and humanitarian values. These are The Verdict of the French Colonial Regime (1925), Prison Diary (1943) and Declaration of Independence (1945).

It is necessary to briefly recount the above to tell a truth, or rather, a simple truth: In the identity of a citizen who lost his country; a Vietnam that lost its name on the map; a young man who sought to save the country, had to change his name dozens of times; had to do 12 jobs to make a living; had to go through a 30-year journey abroad, with 2 arrests, 2 prison sentences, 2 death news, certainly Uncle Ho had no freedom in his activities and earning a living. Yet, Uncle Ho was very free throughout a very large writing career and with that career, he became the person who laid the foundation and gathered the quintessence of Vietnamese literature and journalism in the 20th century.

30 years abroad. More than 25 years of writing. Writing has become a method for revolutionary activities. A weapon of voice. For Uncle Ho, writing is not to leave a literary career, like any other poet or writer of the same period. If there is a career, it is the sovereignty of the Fatherland that is still in slavery, the benefit of the People who are still very miserable. “Freedom for my compatriots, independence for my Fatherland. That is all I know. That is all I understand”…

Cover of "Prison Diary" (Photo)

From 1919 to 1945 in his writing career, Nguyen Ai Quoc - Ho Chi Minh had no need to convince anyone, educate anyone about the concept of writing, about writing experience, other than expressing himself, revealing himself faithfully and completely on all written pages, of all genres - that is, Claims, or Sentences; an extremely simple verse like The Stone for the illiterate masses to understand, to a profound philosophy about life in the situation of a prisoner; a call to fellow countrymen to join the Viet Minh or prepare for a general uprising, to a Declaration of Independence, speaking in the name of history and the nation to the future and humanity.

From 1945, in his position as President, after reading the Declaration of Independence until 1969, announcing his Will after his death, Ho Chi Minh continued his writing career in many genres such as Chinese and Vietnamese poetry; letters, appeals or speeches for professionals... In this field, Ho Chi Minh had the opportunity to express his views on journalism, literature, and art; through which, directly or indirectly, we can know his opinion on freedom in artistic creation.

As a revolutionary, Ho Chi Minh always considered cultural and artistic activities as an activity to reform and create the world in humans. Literature and art do not have an intrinsic purpose. In his Letter to Artists on the occasion of the 1951 Painting Exhibition, Uncle Ho wrote: "Culture and art, like all other activities, cannot be outside, but must be within economics and politics." Generations of Vietnamese artists and the public over the past half century must have taken to heart every word of the above letter, when the resistance war had taken place after 6 years. "Culture and art are also a front. You are soldiers on that front" (1).

Previously, in 1947, in his Letter to the Cultural and Intellectual Brothers of the South, Uncle Ho wrote: “Your pens are sharp weapons in the cause of supporting the righteous and eliminating evil” (1). This is a principled viewpoint in Uncle Ho’s literary and artistic thought. The requirement to serve the revolution in the spirit of Ho Chi Minh does not carry the spirit of imposition, but must be a voluntary, self-conscious activity, a requirement of responsibility, of the conscience of the artist:

“It is clear that when a nation is oppressed, literature and art also lose their freedom. If literature and art want freedom, they must participate in the revolution” (1).

President Ho Chi Minh always researched and sought to add information to each article. Photo: Document

It should be noted that the relationship between literature and politics as stated above by the author does not mean a lowering of the value of literature and art; nor does it mean a separation of politics and literature into two opposing sides, or with a high and low order. In the letter sent above, there is a passage that says: “On behalf of the Government, I thank you for your support. The Government and all Vietnamese people are determined to fight for the right to unify and independence for the country, so that culture, politics, economics, beliefs, and ethics can all develop freely” (1).

Thus, until the nation gains sovereignty and the goal of the revolution is focused on building a new society, aiming at the pursuit of human happiness, the requirement for the free and comprehensive development of political, economic, cultural, religious and ethical aspects will be set out in a holistic relationship, affecting each other; on the other hand, attention must be paid to the specific characteristics and internal, regular requirements for each field of activity, which those assigned or voluntarily selected must understand and apply.

Literature and art need to be free. But the freedom of literature and art needs to be placed within the common freedom of the people and the nation.

Literature and art need freedom. But how to conceive freedom correctly and how to achieve freedom - that is something that needs to be understood and developed on the basis of grasping the specific requirements of revolutionary practice and the internal development laws of literature and art.

Not considering himself a poet, writer, or artist, because that was not his profession, but only admitting that he was a lover of literature and art (2), Ho Chi Minh still left behind an immortal career, standing at the forefront of humanistic and modern values in the history of Vietnamese literature.

That non-professional writer is also someone who always affirms the important role and position of culture and literature. He is very familiar with folk songs, folk songs and the Tale of Kieu. He once considered himself “a small student of L. Tolstoy” (1)... He has a deep understanding of the values of literature and arts and has elevated literature and arts to a very high position as “sharp weapons in the cause of supporting the righteous and eliminating evil”.

The man who fought all his life for the independence, freedom and happiness of the nation and the People was also a very free man in his literary and journalistic creations throughout his 50-year writing career. Writing for the working public who were still in slavery or for the public who had enjoyed independence and freedom and wrote for themselves - Ho Chi Minh always expressed himself in a posture of absolute freedom, not subject to any constraints from himself or the outside world.

(1) Ho Chi Minh: On cultural and artistic work; Truth Publishing House; H.; 1971.

(2) Speech at the closing ceremony of the 2nd National Congress of Literature and Arts, 1957. Excerpted from the above book.

Phong Le

Source

![[Photo] The "scars" of Da Nang's mountains and forests after storms and floods](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/13/1762996564834_sl8-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends a conference to review one year of deploying forces to participate in protecting security and order at the grassroots level.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/12/1762957553775_dsc-2379-jpg.webp)

![Dong Nai OCOP transition: [Article 3] Linking tourism with OCOP product consumption](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/10/1762739199309_1324-2740-7_n-162543_981.jpeg)

Comment (0)