I took a bus along the embankment, under the shade of trees on Catinat Street [now Dong Khoi], where millions of street lamps - simple oil lamps - created an illusion and made one think that Saigon had switched from gas to electricity. Coffee shops, many coffee shops, cast a dim light on the sidewalk.

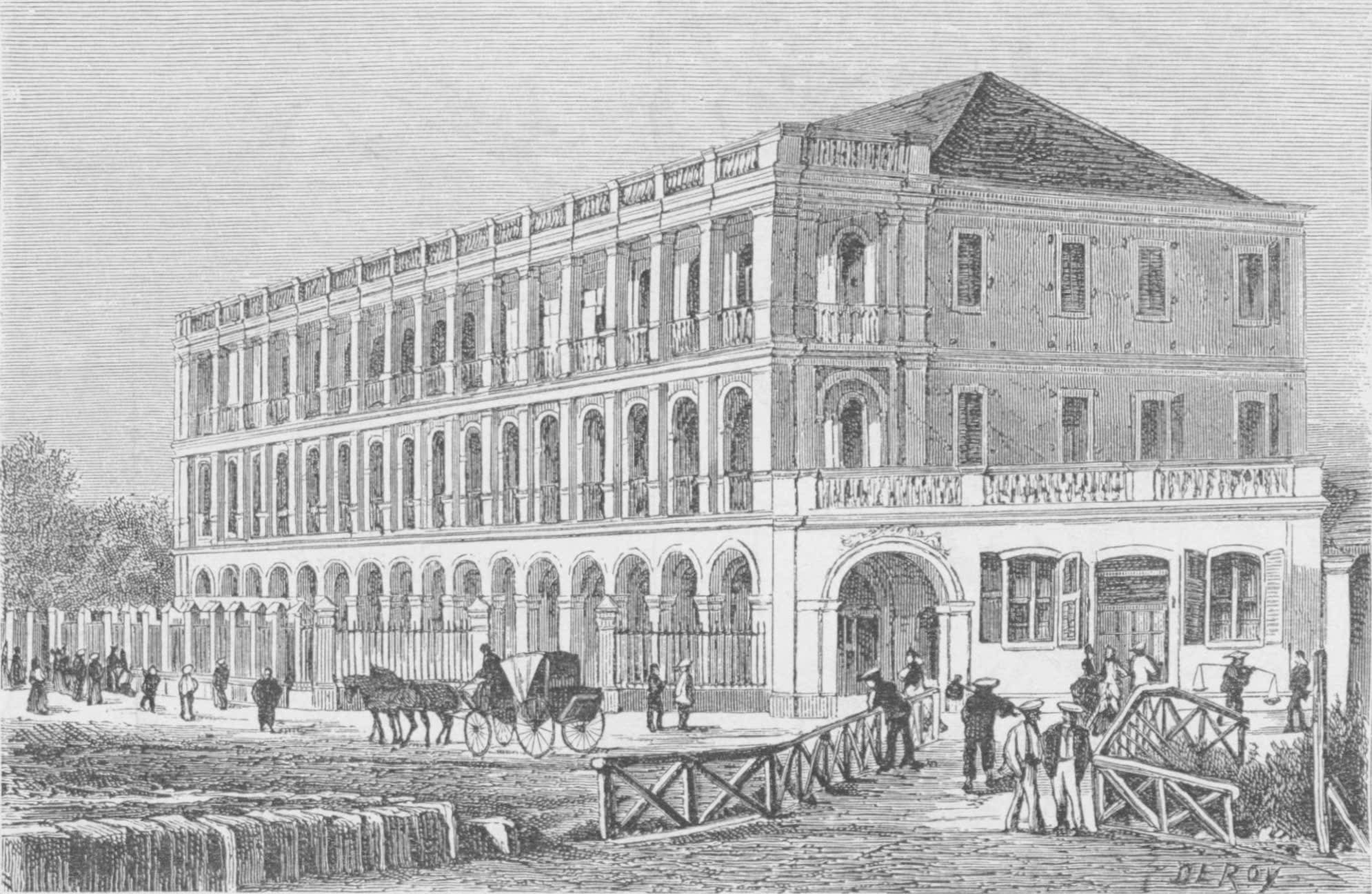

Cosmopolitan Hotel in Saigon in the 1870s. Illustration by A.Deroy, based on a photograph

Photo: National Library of France

Right in the middle of a garden with manicured lawns, with palm trees, giant palm trees interspersed with rose bushes, is a lovely theater with columns like the Odéon theater that we mistake for a casino.

In front of the hotels, flower sellers bustled about: boys of six or eight years old hawking bouquets of hibiscus, green and pink gardenias. Little girls carry large umbrella-like bouquets on their heads. From the stalls of the Chetty [Indian] Chays, who were part money changers, part tobacconists and part grocers, Aryans from the Malabar or Coromandel coast, to the department stores selling all sorts of Chinese and Japanese vases, reminiscent of the exoticism of the hot springs, to the souvenir shops filled with all the accessories that are essential to modern resorts. All that was missing was the clear, sweet stream. The view by day and by night was just like [that resort].

I see Saigon as a stage perspective too wide for the play being performed: the stage of the Opera house with many characters standing and sitting comfortably between two screens.

The stage is large and deserted at some hours of the day, but at other times this European population of two to three thousand, gathered at the chosen site, gives the feeling of a much more crowded metropolis with the liveliness, glamor of a riverside city and the chatter.

A truly beautiful city that Joanne or Baedeker will not forget to describe in detail. Since I do not want to, and especially do not have enough time to write a Guide de l'étranger à Saïgon, allow me to summarize and not describe the architectural works with their functions or utilities. Therefore, the reader will not know the plan of the Supreme Court [of Indochina] or the architectural style of the temple of the Department of Registration and Public Administration. The reader will also not know the number of volumes preserved in the library. Regarding the Palace of the Governor-General of Indochina, a building that has been rarely occupied in recent years and could make an Indian viceroy envious, I will only say briefly that it is "the most beautiful palace in the world ", like the quintessence of 17th-century France.

The same goes for museums. Saigon built a large, luxurious colonial museum; but when it was realized that the best works in the museum's collections were regularly disappearing from their glass cases to enrich collections in the mother country, it was wisely decided not to push this experiment any further and the building became the residence of the Deputy Marshal [of Cochinchina].

All the offices, however, - God knows how many of them - civil and military institutions are spacious, and sometimes even more comfortable than those in Europe. The climate demands it, and I think that in the hot latitudes the architects have combined iron and brick more skillfully than ever before. I especially recommend the reader to visit the Post and Telegraph Department, which has no equal in any great French city except Paris. America is the only place where I have seen such a practical arrangement, the great hall with its walls decorated with maps, colored diagrams, pictures and charts, the public at a glance has information which elsewhere would cost them the price of constant effort, of strenuous searches from one shop to another.

As for the barracks, it suffices to say this: the British, who were well versed in colonial planning, could not have found a better model when they built new barracks in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Equally remarkable is the Hospital with its independent buildings, shady grounds, and lawns, which do not at all resemble a place of suffering. If the white cap of a nun did not appear faintly in the darkness of the porches, one might think that one was in a resort planned for relaxation of the mind and contemplation, for receiving gentle, pure souls, balancing work and dreams, away from the noise of the city, in harmony with trees and flowers. This impression is even more evident at this time of year. The winter weather is pleasant: serious illnesses are less or non-existent, a few groups of convalescent patients walk back and forth on the paths, their steps steady and their conversation cheerful. Others lie leisurely on chairs with books or newspapers in their hands. Everything is peaceful, but not at all sad. And I told myself that the poor people who are sick with fever should feel secure coming here, to have their fever reduced and be cared for in this quiet environment, where the pain is soothed by the chirping of birds under the green foliage.

In the Far East, there are two places whose names sound like they are sow sad, but which are places where tourists want to stop, without any sadness: the British Cemetery in Hong Kong and the Hospital in Saigon. (to be continued)

(Nguyen Quang Dieu quoted from the book Around Asia: Cochinchina, Central Vietnam , and Bac Ky, translated by Hoang Thi Hang and Bui Thi He, AlphaBooks - National Archives Center I and Dan Tri Publishing House published in July 2024)

Source: https://thanhnien.vn/du-ky-viet-nam-loi-song-sai-gon-185241203225005737.htm

Comment (0)