On February 26, Project Syndicate published an article titled “ How the US CHIPS Act Hurts Taiwan” by a group of Taiwanese scholars, including Chang-Tai Hsieh , Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago ; Burn Lin , Dean of the School of Semiconductor Research at National Tsinghua University, former Vice President of TSMC ; Chintay Shih , Professor at National Tsinghua University , former President of the Taiwan Industrial Technology Research Institute . The group of scholars who co-signed the article are Tainjy Chen , Dean of the Taipei School of Economics and Political Science at National Tsinghua University and former Minister of National Development of Taiwan; Huang-Hsiung Huang , President of the Taipei Foundation for Political Science and Economics, former Chairman of the Transitional Judicial Commission, and former member of the Procuratorate and Legislative Yuan in Taiwan ; W. John Kao, President of National Tsinghua University, Taipei ; Hans H. Tung , Professor of Political Science at National Taiwan University ; and Ping Wang , Professor of Economics at Washington University in St. Louis. (National Tsinghua University is the university in Taipei, Taiwan, with the same name, but not the one in Beijing .) The article is not long, but provides a lot of information and interesting assessments, especially for countries and economies that are looking to participate in the global semiconductor supply chain. We would like to introduce this article. |

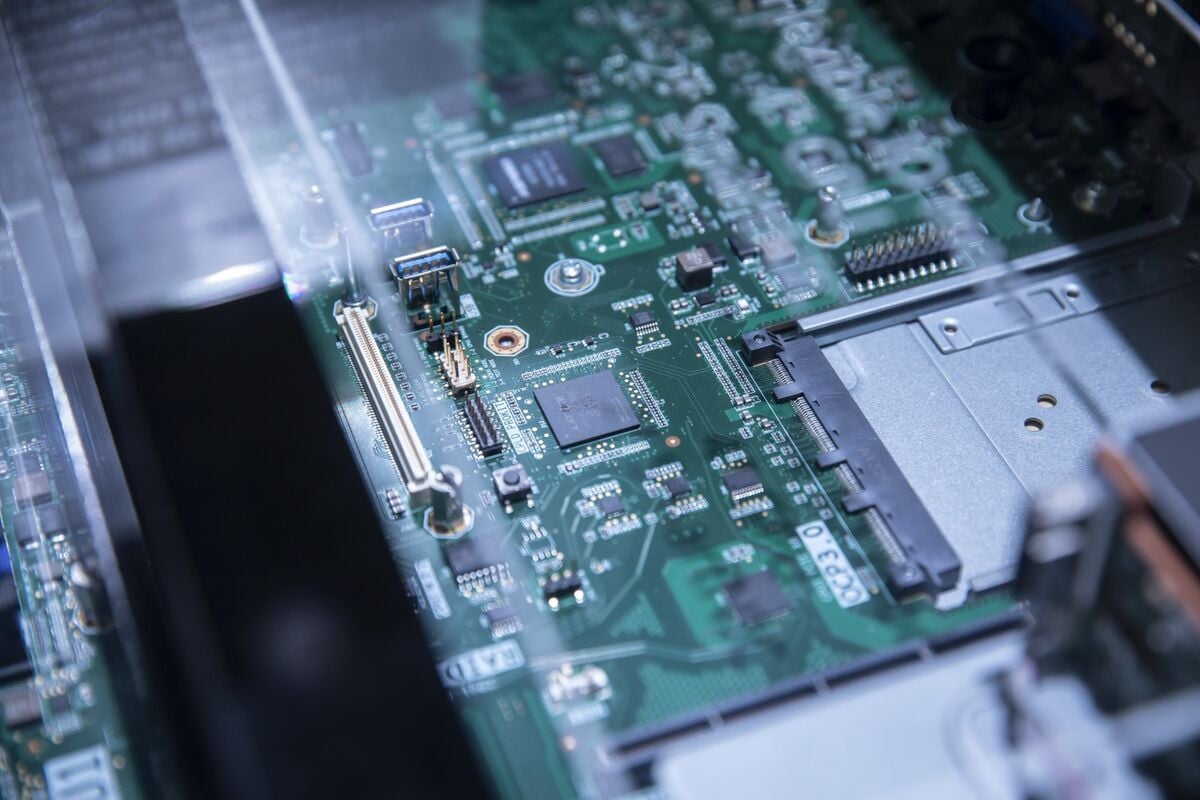

The concentration of advanced semiconductor manufacturing in Taiwan has raised concerns in the US about supply chain vulnerability. The US Science and Chips Act seeks to address that vulnerability with $52 billion in subsidies to encourage semiconductor manufacturers to move to the US.

But the bill would fail to achieve that goal, and could even weaken Taiwan's most important industry.

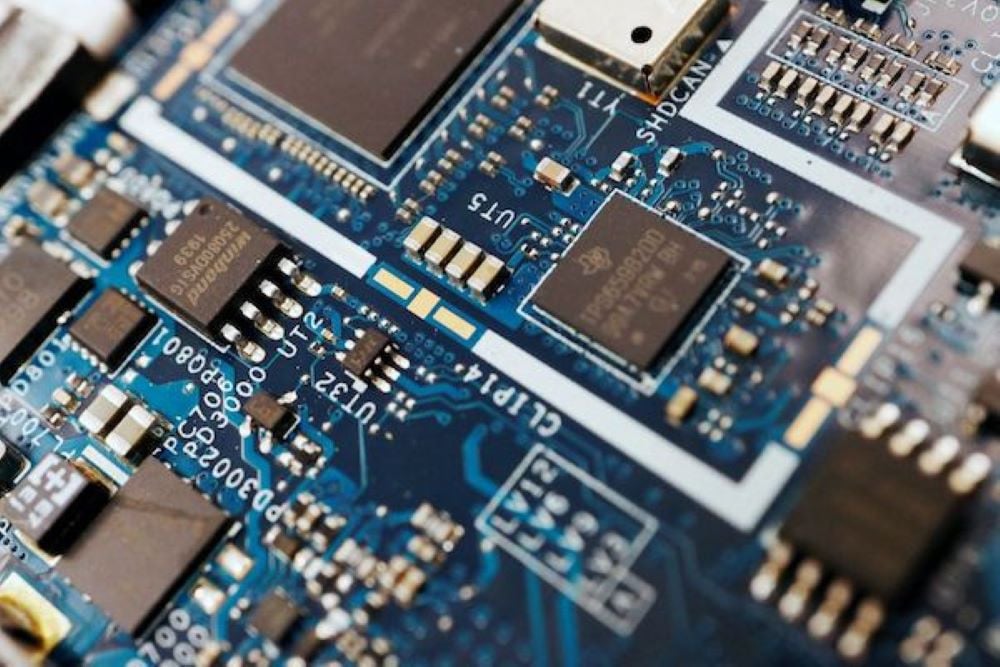

The semiconductor industry today is dominated by specialist companies based around the world. Taiwan-based TSMC focuses solely on made-to-order manufacturing, mainly of high-end chips, while other important parts of the semiconductor ecosystem include US companies such as AMD, Nvidia and Qualcomm (chip designers), lithography specialist ASML in the Netherlands, Japan’s Tokyo Electron (chip manufacturing equipment) and Britain’s Arm (software used to design chips).

All this expertise provides two key benefits. First, each part of the global supply chain can focus and improve on what it does best, benefiting other parts of the supply chain. Second, increased global capacity across all segments of the supply chain makes the industry more resilient to demand shocks.

The price of specialization is that the industry is vulnerable to supply shocks. The United States and Japan have offered large subsidies to TSMC to relocate, and TSMC now plans to build new facilities in Kumatomo, Japan, and Phoenix, Arizona.

The Japan facility will be completed as planned, but the Phoenix project has fallen significantly behind schedule and fewer and fewer TSMC suppliers plan to locate there.

TSMC’s experience in Camas, Washington (Greater Portland) over the past 25 years has cast further doubt on the promise of the Phoenix project. Despite initial hopes that the Portland facility would become TSMC’s flagship in the U.S. market, the company has struggled to find enough workers to remain competitive. After a quarter century with the same training and equipment, manufacturing costs in the U.S. remain 50 percent higher than in Taiwan. As a result, TSMC has decided not to expand its Portland operations.

The fundamental problem is that while the US workforce is highly skilled in chip design, the country lacks the desire or skills needed to manufacture chips.

TSMC Phoenix will continue to struggle because there are too few American workers with the skills needed to manufacture semiconductors. Therefore, seeking economic security by shifting semiconductor production to the US is a “costly and futile homework exercise,” as TSMC founder Morris Chang warned in 2022. The $52 billion in the CHIPS Act may seem like a large number, but it is not enough to create a self-sustaining semiconductor ecosystem in Phoenix.

Industrial policy can work, but only under the right circumstances. TSMC is a testament to that. Taiwan’s industrial planners clearly chose a niche based on their existing strengths in manufacturing. They didn’t try to copy Intel, the leading semiconductor company at the time, because too few Taiwanese workers had the design skills needed to do so. Japan’s subsidies to attract TSMC were likely successful because Japan already had plenty of skilled manufacturing workers.

Like war, industrial policy has many unintended consequences. The availability of free money threatens to transform TSMC from a company focused on relentless innovation to one more concerned with securing subsidies. The more TSMC’s management tries to fix its problems in Phoenix, the less it focuses on other issues. Those issues are so serious that they are believed to have led to the resignation of TSMC Chairman Mark Liu in December 2023.

The CHIPS Act poses three major risks. First, if TSMC loses its focus on innovation, the biggest losers will be its customers and suppliers, most of whom are American companies. The broader AI revolution—much of which is powered by TSMC-made chips—will grind to a halt. Furthermore, TSMC could reduce investment in expanding capacity in Taiwan, leaving the entire industry less resilient to demand spikes.

Ultimately, TSMC could lose its way to the point where another company replaces it as the leader in advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Many in Taiwan have viewed the CHIPS Act as an attempt by the United States to steal Taiwanese technology.

The CHIPS Act, while well-intentioned, is poorly designed. Instead of creating a sustainable semiconductor manufacturing cluster in the US, it could cause lasting damage to TSMC and ultimately to the Taiwanese economy, the article said.

Building capacity in countries like Japan (where operations are less likely to damage TSMC's business) may be a wiser strategy.

(translated and introduced)

Source

![[Photo] Closing ceremony of the 18th Congress of Hanoi Party Committee](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/17/1760704850107_ndo_br_1-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Nhan Dan Newspaper launches “Fatherland in the Heart: The Concert Film”](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/16/1760622132545_thiet-ke-chua-co-ten-36-png.webp)

![[Infographic] 8 cancers related to tobacco](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/18/1760748667221_anh-chup-man-hinh-2025-09-26-110-2182-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)