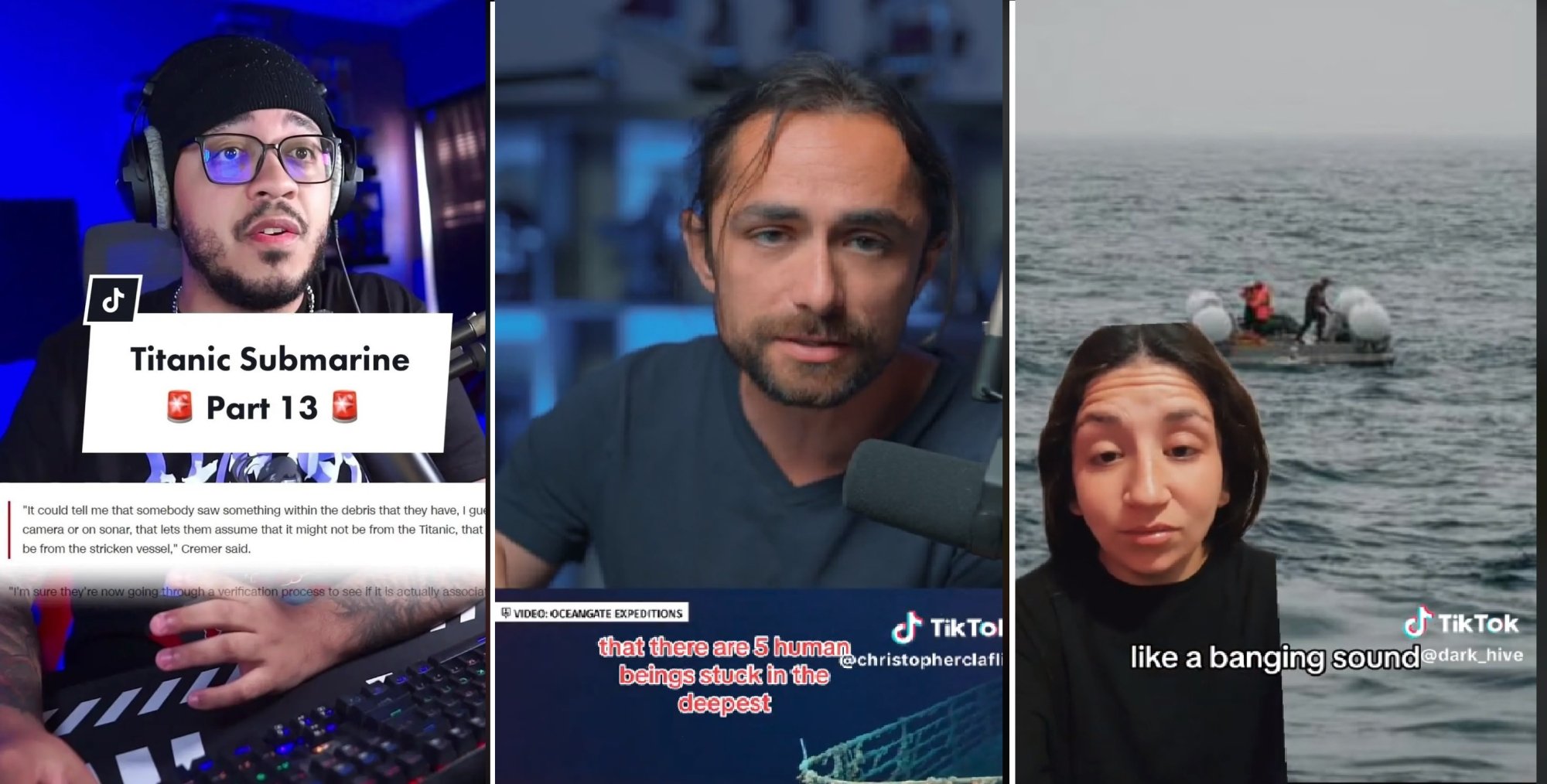

Over the past week, the world was shocked by the disappearance of the submarine Titan. In addition to news reports, expert and law enforcement analysis, a huge amount of other content has also appeared on social networks, through the stories of those who worked on the submarine, experts in carbon dioxide (CO2) filtration systems, and even people with no expertise in this field.

Titan submersible. Photo: Independent

"Journalists at home"

Of course, along with social networks like Facebook, YouTube or Twitter, TikTok is not out of the game. Videos critique, calling for sympathy, interacting, etc. continuously appear. Even self-proclaimed psychics on TikTok also participated in commenting and predicting the incident.

But eventually, the wreckage of the ship was found. Signs showed that the hull was defective and the ship had been crushed by water pressure. All five people died. It shows that almost all the "investigations" of the "keyboard experts" were "completely wrong".

That further strengthens the popularity and arguably the problem of "self-communication" of "garden journalists", "home journalists" or "citizen journalists" on TikTok, as well as other social networks.

In this incident, many TikTokers quickly released videos related to the Titan ship, the Titanic, and created a significant growth in followers and engagement in the past few days.

This shouldn't come as a shock to those who study media. This trend has been going on for years. It seems to have become a template for what disasters happen on social media when news of a breaks.

Thanks to TikTok's algorithm, posting about a major disaster like Titan can make a video go viral very quickly. Getting more views and attention can lead to higher TikTok earnings, or lucrative advertising contracts down the road.

Ahren Gray, a 29-year-old San Diego content creator who also owns a streetwear brand inspired by the video game “Dungeons and Dragons,” had just over 100,000 followers before he started posting about the Titan. Now he has more than 300,000 and counting. Gray, a longtime “Titanic fan,” has a tattoo of Titanic actress Kate Winslet on his thigh.

“As the numbers started to climb, I felt more and more pressure because those people were in trouble and danger at the bottom of the ocean at the time I was making the videos,” Gray said. “As the videos started to go viral, I started to think about my ethics.”

Gray posted his videos in multiple parts, teasing viewers with dramatic music and asking them to leave a comment if they wanted to see the next part. However, he stopped asking because he felt it was too much of a “clickbait” tactic. Like many content creators, Gray calls his job “reporting.”

The danger of spreading rumors

More and more people, especially young people, are turning to TikTok as a search engine and source for news. Justin Shepherd, 41, a salesman and content creator in Nashville, has amassed more than 75,000 followers since he started posting about Titan. He has posted more than 20 TikTok videos and hosted three livestreams that delved into the minutiae of sonar detection and Coast Guard rescue efforts.

Many experts on social media have shown their talent in "investigating" the Titan explosion while sitting at home. Photo: TikTok

When he started his TikTok account in 2020, he mainly posted about his family. But the account gained traction when he started posting about the murder of a woman named Gabby Petito in the US in 2021. Since then, he has focused on videos summarizing investigations into grisly events.

“A lot of people call me an internet sleuth,” Justin said. “I'm not a sleuth at all. I get the news, I read it, I figure out what's true, I figure out what's interesting, and I summarize it in a way that's quick and easy for people to understand.”

He says he checks every piece of information, verifying it with at least two news sources before posting. His Titan videos include screenshots of articles from Rolling Stone, TMZ, and CNN. He tries not to post viral theories, even though they might get more views.

“There are some really great, trustworthy creators,” he said. “But at the same time, there are also people who are sensationalists, trying to spread rumors or rumors just to get more views.”

Hoang Ton (according to NYT, TikTok)

Source

![[OCOP REVIEW] Bay Quyen sticky rice cake: A hometown specialty that has reached new heights thanks to its brand reputation](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/3/1a7e35c028bf46199ee1ec6b3ba0069e)

Comment (0)