In August 1967, starting from the proposal of Ambassador Arvid Pardo, Head of the Maltese Delegation to the United Nations, the idea of an international treaty regulating the seabed and oceans, serving the common interests of mankind, was born. In 1973, the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea was officially held with the mission of negotiating a comprehensive international treaty on the fields of sea and ocean management. After 9 years of negotiation, the draft UNCLOS 1982 was adopted on April 30, 1982 with 130 votes in favor (4 votes against and 17 abstentions) (1) . On the day of official opening for signing (December 10, 1982), 117 countries signed the Convention. On November 16, 1994, one year after 60 member states ratified it, the 1982 UNCLOS officially came into effect. To date, 168 member states have ratified the 1982 UNCLOS (2) .

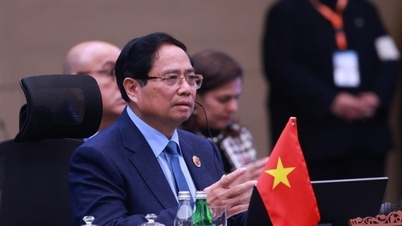

Plenary session of the 30th Conference of States Parties to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)_Source: baoquocte.vn

Comprehensive and equitable legal framework

Before the UNCLOS in 1982, in 1958, the United Nations held the first Conference on the Law of the Sea and achieved the first international legal framework to regulate issues of seas and oceans through four Conventions on territorial seas and contiguous zones, continental shelves, high seas, fishing and conservation of living resources of the high seas and a Protocol on the settlement of disputes (3) . This was a big step towards establishing the first international legal order at sea, harmonizing the different interests of coastal states and the common interests of the international community. However, the 1958 Conventions revealed many limitations.

Firstly, the determination of maritime boundaries has not been completed because countries have not yet agreed on the width of territorial waters and fishing zones. Secondly, the division of rights and interests at sea is biased towards protecting the interests of developed countries, ignoring the interests of developing countries and geographically disadvantaged countries (4) . Thirdly, the international seabed beyond the continental shelf limits of coastal countries is completely left open, not regulated by international legal regulations. Fourthly, the protocol on dispute settlement narrows the option of compulsory settlement through the International Court of Justice (ICJ), so it does not receive widespread support (5) . Fifthly, although the problem of marine environmental degradation and pollution has been anticipated, the regulation on the conservation of marine biological resources at sea is not sufficient in terms of sources of pollution, the scope of pollution and sanctions to handle violations of marine environmental pollution.

The 1982 UNCLOS overcame the limitations of the 1958 Conventions and created a fair legal framework, harmonizing the interests of different groups of countries such as between coastal and landlocked countries, or geographically disadvantaged countries between developed countries and developing and underdeveloped countries.

Specifically, for the first time, the 1982 UNCLOS completed the regulations on determining the boundaries of maritime zones from internal waters, territorial waters, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones, continental shelves, high seas and the Area (international seabed). In particular, the exclusive economic zone regime was born as a result of protecting the economic privileges of developing countries and newly independent countries in the national liberation movement in the 60s of the 20th century. This is the first legal regime that has been regulated taking into account the characteristics of the natural distribution of marine living resources within 200 nautical miles (6) and establishing fairness for all countries, excluding regulations based on traditional and historical fishing rights established by countries with developed scientific and technological conditions since before the Convention was born.

Regarding the continental shelf, the 1982 UNCLOS stipulates criteria for determining the continental shelf boundary based on objective geographical criteria on the basis of respecting the principle that land dominates the sea. Accordingly, the continental shelf is a geological concept, a natural extension of the land territory of coastal states. Therefore, the minimum width of the legal continental shelf that countries can determine is 200 nautical miles from the baseline. Countries with a natural continental shelf wider than 200 nautical miles are allowed to determine an extended legal continental shelf (7) . However, to ensure fairness and objectivity, the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) (8) will have the authority to review the method of determining the extended continental shelf of coastal states and only the extended continental shelf boundaries that are determined in accordance with the recommendations of the (CLCS) will have binding value and receive recognition from other countries.

The interests of landlocked or geographically disadvantaged countries are also taken into account when a series of regulations on transit and exploitation of surplus fish stocks are stipulated in the regulations on exclusive economic zones (9) . In addition, the characteristics of archipelagic states are also considered for the first time and codified into the legal status of archipelagic states (10) .

In particular, in addition to inheriting the provisions on freedom of the seas, the 1982 UNCLOS for the first time established a legal regime for the Area with the characteristics of being a common heritage of mankind. In particular, the Seabed Authority (ISA) was established to develop regulations on resource exploitation in the Area and distribute benefits fairly to member states (11) . The Agreement on the Implementation of Part XI was also signed in 1994 to supplement specific regulations on management and exploitation of the Area for the 1982 UNCLOS.

Peaceful mechanism for resolving maritime disputes

The United Nations Charter has stipulated the principle of peaceful settlement of international disputes. Accordingly, disputes must be resolved through measures such as negotiation, investigation, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, courts and regional and international organizations or any other peaceful means chosen by the parties themselves (12) . The 1982 UNCLOS reaffirmed the spirit of this principle, while skillfully combining peaceful measures to create a dispute settlement mechanism suitable to the specific characteristics of disputes between member states regarding the interpretation and application of the Convention.

Accordingly, UNCLOS 1982 gives priority to agreements on dispute settlement measures that the parties have agreed upon in advance. If there is no existing agreement on dispute settlement measures, UNCLOS 1982 requires the parties to negotiate directly through the provision of exchange of views as a compulsory measure. In addition, UNCLOS 1982 encourages the parties to use conciliation as a voluntary option to facilitate direct negotiations.

However, the mandatory exchange of views is not valid indefinitely. The Convention only requires the parties to have the obligation to exchange views within a reasonable period of time (13) . After that period, if the parties do not reach a solution to resolve the dispute, the judicial bodies will be the next choice. For more flexible options, the 1982 UNCLOS stipulates that the parties can declare to choose one of four judicial bodies, including: the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), the Arbitration established under Annex VII and the Arbitration established under Annex VIII (14) . In which, in addition to the ICJ, which is a court established alongside the United Nations since 1945, the remaining institutions are all newly established under the provisions of the 1982 UNCLOS. Notably, the 1982 UNCLOS creates an automatic default mechanism. Accordingly, if the parties do not make a declaration of choice of jurisdiction, or choose different agencies, the Arbitration established under Appendix VII is the compulsory competent authority to resolve the dispute.

This default mechanism provision ensures both flexibility in choosing the dispute settlement agency and efficiency when a party can use the right to unilaterally initiate an arbitration established under Annex VII to resolve disputes with another member state regarding disagreements related to the interpretation and implementation of the 1982 UNCLOS. The right to unilaterally initiate a lawsuit is provided on the basis that the 1982 UNCLOS is a comprehensive Convention, member states are not allowed to make reservations to any provisions when ratifying the Convention, and therefore, voluntarily bound themselves to the compulsory jurisdiction of the dispute settlement mechanism prescribed in Part XV of the Convention.

However, in order to create more flexibility for the dispute settlement mechanism, and also to overcome the limitation of the rigid provisions of the 1958 Dispute Settlement Protocol (which led to many countries not ratifying), the 1982 UNCLOS provided for additional exceptions and limitations. Accordingly, disputes related to the interpretation or application of the provisions of the Convention on the exercise of sovereign rights and jurisdiction of coastal states are naturally excluded from compulsory dispute settlement mechanisms of judicial bodies (15) . Disputes related to border delimitation, maritime boundaries, military activities of vessels, or being considered by the United Nations Security Council are also excluded by choice from compulsory dispute settlement mechanisms of judicial bodies (16) . Accordingly, if a member state makes a declaration excluding these three selected types of disputes, other states are not allowed to initiate lawsuits against these disputes to the judicial bodies as prescribed by the Convention.

Although some disputes are excluded by default or by choice from compulsory dispute settlement through judicial bodies, member states are still obliged to settle disputes by other peaceful means, including the obligation to exchange views. In particular, the 1982 UNCLOS provides that for these excluded disputes, a party may unilaterally request compulsory conciliation to make recommendations on dispute settlement measures.

It can be said that with flexible and creative provisions, UNCLOS 1982 has created a multi-layered dispute resolution mechanism, ensuring flexibility and freedom of choice for the parties regarding dispute resolution measures and agencies, while facilitating the process of dispute resolution of the parties. In particular, the dispute resolution mechanism of UNCLOS 1982 is the first pioneering mechanism to regulate the unilateral right of a member state to file a lawsuit before an international judicial body. Thanks to this provision, many disputes between countries at sea have been resolved and disagreements between countries have been narrowed. Since the birth of UNCLOS 1982, 29 maritime disputes have been resolved through ICJ, 18 disputes have been resolved through ITLOS and 11 disputes have been resolved through Arbitration established under Annex VII.

Sustainable values, towards the future

Not only creating a comprehensive and universal legal framework, a creative dispute resolution mechanism, promoting peace and stability at sea, the 1982 UNCLOS also has progressive provisions, linked to the orientation of sustainable and future-oriented sea and ocean governance. The obligation to cooperate is the focus of the Convention when it is mentioned 60 times in 14 different provisions in the Convention, including provisions on cooperation in the field of protection and preservation of the marine environment, cooperation in marine scientific research, cooperation in science and technology transfer, cooperation in semi-enclosed seas, cooperation in suppressing crimes at sea...

In the field of protection and preservation of the marine environment, the 1982 UNCLOS provides comprehensive regulations, assigning responsibilities and obligations of coastal states within the exclusive economic zone; at the same time, determining the obligation of cooperation between states within the high seas. In particular, Part XII of the 1982 UNCLOS is dedicated to regulating the protection and preservation of the marine environment with 11 sections.

In addition to Section 1, which stipulates general obligations applicable to states, Part XII of the 1982 UNCLOS has specific provisions on cooperation at the regional and international levels, technical assistance to developing countries, and assessment of the impact of sources of marine pollution. In order to develop regulations on preventing marine pollution at the national and international levels and determine responsibility for acts causing marine pollution, the 1982 UNCLOS classifies the causes of pollution from land sources, from exploitation activities in the Area, from vessels, from dumping and dumping into the sea, from air and atmosphere. In addition, the 1982 UNCLOS also has specific provisions for ice-covered sea areas and determines the relationship with other specialized international treaties in the field of environmental protection.

In the field of marine scientific research, the 1982 UNCLOS emphasizes the need to ensure harmony between the sovereignty and jurisdiction of coastal states on the one hand and the interests of the community on the other. Accordingly, the Convention stipulates that states and international organizations disseminate information and knowledge resulting from marine scientific research. At the same time, the Convention also requires states and international organizations to cooperate and facilitate the exchange of data and scientific information and the transfer of knowledge gained from marine scientific research, especially to developing countries as well as to enhance capacity building for developing countries in the field of marine scientific research (17) .

In particular, recognizing the importance of science and technology, and at the same time, overcoming the inequality between countries in this field, the 1982 UNCLOS dedicated Part XIV to regulating the issue of technology transfer. Accordingly, the Convention defines the principle of countries cooperating directly, or through international organizations, to actively facilitate the development and transfer of marine science and technology under fair and reasonable forms and conditions. The Convention pays special attention to the need for technical assistance of developing countries, landlocked countries or geographically disadvantaged countries, in the exploration, exploitation, protection and management of marine resources, protection and preservation of the marine environment, marine scientific research and other activities to be carried out in the marine environment suitable to promote the social and economic progress of developing countries. The Convention also encourages the establishment of national and regional marine scientific and technological research centers to promote and encourage marine scientific research aimed at the use and conservation of marine resources for sustainable development.

Towards the goal of conserving valuable marine genetic resources for sustainable development in the future, currently, member countries of the Convention are participating in the process of negotiating and signing an agreement on biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (18) . At the same time, along with the development of science and technology and new emerging issues, such as the negative impacts of climate change, rising sea levels, and the impacts of epidemics, member countries will continue to discuss to supplement the provisions of the Convention.

Vietnam - a responsible member of UNCLOS 1982

Immediately after the country's reunification, Vietnam actively participated in the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea; at the same time, issued a Declaration on territorial waters, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones, and continental shelves on May 12, 1977 (19) . Although it was announced in 1977, the content of this Declaration was completely consistent with the provisions of UNCLOS signed by countries in 1982. In 1994, Vietnam was the 63rd country to ratify UNCLOS 1982, before the Convention officially came into effect in December 1994. The National Assembly's Resolution ratifying UNCLOS 1982 clearly affirmed that, by ratifying UNCLOS 1982, Vietnam expressed its determination to join the international community in building a fair legal order, encouraging development and cooperation at sea (20) .

After becoming an official member of UNCLOS in 1982, Vietnam has issued many domestic legal documents to specify the provisions of the Convention in many fields, such as territorial borders, maritime, fisheries, oil and gas, marine and island environmental protection... In particular, in 2012, Vietnam issued the Vietnam Sea Law with most of the contents compatible with UNCLOS 1982.

In 2009, fulfilling its obligations under the 1982 UNCLOS, after 15 years of becoming a member of the Convention, Vietnam submitted its extended continental shelf boundary in the northern area to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf ( 21) . In addition, Vietnam also cooperated with Malaysia to submit to the CLCS the common extended continental shelf boundary in the southern part of the East Sea, where the two countries have overlapping, undelimited continental shelves (22) .

With the spirit of equality, mutual understanding and respect, and respect for international law, especially the 1982 UNCLOS, Vietnam has successfully delimited overlapping maritime areas with many neighboring countries. Along with maritime delimitation, Vietnam and China also reached an agreement on fisheries cooperation in the Gulf of Tonkin, thereby establishing a joint fishing cooperation area and joint patrols to prevent crimes and violations at sea (23) .

Up to now, the maritime delimitation agreements between Vietnam and neighboring countries have been implemented in accordance with the principle of peaceful settlement of international disputes, in accordance with international law, especially the 1982 UNCLOS, contributing to promoting peaceful, stable and developing relations between Vietnam and neighboring countries. In addition to maritime delimitation, Vietnam has also reached an agreement with Cambodia on historical waters in the undelimited maritime area between the two countries. At the same time, together with Malaysia, it has established a joint oil and gas exploitation area in the undelimited overlapping continental shelf area between the two countries.

In maritime areas that are still being encroached upon and have not been delimited, with neighboring countries such as the overlapping area with Cambodia, the tripartite overlapping area between Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand, or the potential overlapping area between Vietnam and Brunei, as well as between Vietnam and the Philippines (24) , Vietnam always respects the sovereignty and jurisdiction of coastal countries over their exclusive economic zones and continental shelves, while promoting negotiations to find fundamental and long-term solutions. Vietnam supports maintaining stability on the basis of maintaining the status quo, not taking actions that further complicate the situation, not using force or threatening to use force.

Particularly with the two archipelagos of Hoang Sa and Truong Sa, on the one hand, Vietnam affirms that it has sufficient historical and legal evidence to prove Vietnam's sovereignty over these two archipelagos; on the other hand, Vietnam determines that it is necessary to distinguish the issue of resolving disputes over the Hoang Sa and Truong Sa archipelagos from the issue of protecting the sea areas and continental shelf under Vietnam's sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction based on the principles and standards of the 1982 UNCLOS. On that basis, Vietnam has signed and implemented the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the East Sea (DOC), and is actively negotiating with China and member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Code of Conduct in the East Sea (COC).

Vietnam People's Navy soldiers before the flag salute on Truong Sa Island, Khanh Hoa Province _Photo: Vu Ngoc Hoang

On October 22, 2018, the Resolution of the 8th Central Conference of the 12th tenure on "Vietnam's sustainable marine economic development strategy to 2030, vision to 2045" was issued. The Strategy clearly defines that "The sea is a component of the sacred sovereignty of the Fatherland, a living space, a gateway for international exchange, closely linked to the cause of building and defending the Fatherland" (25) . In addition to the goals of developing a blue marine economy, conserving biodiversity, preserving and promoting historical traditions and marine culture, combined with the acquisition of advanced and modern science and technology, and the use of high-quality human resources, the Strategy defines a vision to 2045 that Vietnam will proactively and responsibly participate in solving international and regional issues related to the sea and ocean.

In this spirit, in 2021, Vietnam and 11 other countries founded the 1982 UNCLOS Friends Group to create an open and friendly forum for countries to discuss issues related to the sea and ocean, thereby contributing to the full implementation of UNCLOS (26) . Currently, Vietnam is and will continue to proactively and actively participate in multilateral forums, discussing emerging issues of the sea and ocean such as biodiversity conservation in areas beyond national jurisdiction, responding to the negative impacts of climate change on the sea and ocean, and managing activities at sea in the context of new non-traditional security challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, human trafficking, illegal migration, etc.

Often considered a “Constitution for the Oceans”, the signing of UNCLOS 40 years ago was a historic milestone in the development of international law, creating a comprehensive legal framework for peaceful and stable maritime governance, promoting cooperation between countries and sustainable development of seas and oceans. The United Nations - the multilateral organization with the most members in the world today - has repeatedly recognized the role of UNCLOS 1982 and emphasized the need to comply with the Convention in all activities at sea and ocean (27) . ASEAN in its high-level statements has also always emphasized the universal value and importance of implementing UNCLOS 1982 to maintain peace, stability and manage and peacefully resolve maritime disputes in the region. As a coastal country, an active and responsible member, Vietnam always affirms that the 1982 UNCLOS is one of the provisions of international law that plays a key role in the management and development of the national marine economy; at the same time, it is the basis for Vietnam to peacefully resolve maritime disputes with neighboring countries, towards peaceful and sustainable management of the East Sea./.

----------------------------

(1) Gabriele Goettsche-Wanli: “The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: Multilateral Diplomacy at Work”, No. 3, Vol. LI, United Nations, December 2014, https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/united-nations-convention-law-sea-multilateral-diplomacy-work

(2) See: List of countries that signed and ratified UNCLOS in 1982, https://www.un.org/depts/los/reference_files/UNCLOS%20Status%20table_ENG.pdf

(3) Full text of the four 1958 Conventions and one Protocol on the Law of the Sea, https://legal.un.org/avl/ha/gclos/gclos.html

(4) Article 2 of the Continental Shelf Convention stipulates that countries can determine the continental shelf to the limit according to the exploitation capacity. This is a criterion that depends entirely on the level of development of science and technology and the strengths of developed countries.

(5) The Protocol on Settlement of Disputes has been ratified by only 18 countries. In addition to granting compulsory jurisdiction to the ICJ, the Protocol also leaves open the jurisdiction of other courts and tribunals if the countries reach a common agreement. However, the ultimate goal is still to establish the compulsory jurisdiction of a judicial body to settle maritime disputes. See: “List of ratifying countries”, https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=08000002800332b0

(6) Trước khi có quy định của UNCLOS năm 1982, tại Tuyên bố Xan-ti-a-gô năm 1952, ba quốc gia khu vực Mỹ La-tinh, bao gồm: Chi-lê, Ê-cu-a-đo và Pê-ru, là những nước đầu tiên đưa ra yêu sách vùng đánh cá 200 hải lý với lập luận rằng đây thường là khu vực biển nông, nhiệt độ ấm, phù hợp với sự sinh trưởng và phát triển của các loài cá. Xem: SN Nandan: “The Exclusive Economic Zone: A Historical Perspective” (Tạm dịch: Vùng đặc quyền kinh tế: Một viễn cảnh lịch sử), https://www.fao.org/3/s5280T/s5280t0p.htm

(7) Thềm lục địa mở rộng có thể có chiều rộng đúng bằng thềm lục địa tự nhiên, hoặc bằng 350 hải lý kể từ đường cơ sở hoặc 100 hải lý kể từ đường đẳng sâu 2.500m. Chi tiết về các phương pháp xác định chiều rộng thềm lục địa pháp lý được quy định tại Điều 76 UNCLOS năm 1982

(8) Ủy ban Ranh giới thềm lục địa (CLCS) là một trong ba cơ quan được thành lập theo UNCLOS năm 1982 nhằm xem xét bản đệ trình ranh giới thềm lục địa ngoài 200 hải lý của các nước. Ủy ban bao gồm 21 thành viên, đại diện cho 5 khu vực địa lý

(9) Công ước dành riêng Phần X với 9 điều khoản từ Điều 124 - 132; hai điều khoản trong Quy chế của Vùng đặc quyền kinh tế (Điều 69, 70) và Điều 254 về nghiên cứu khoa học biển để quy định về quyền của các quốc gia gặp bất lợi về mặt địa lý và không có biển

(10) Quốc gia quần đảo, do đặc thù cấu tạo chỉ bởi quần đảo, nhưng bị chia cắt về mặt địa lý giữa các đảo khác nhau, nên được áp dụng quy chế riêng, quy định tại Phần IV, từ Điều 46 - 54. Theo đó, quốc gia quần đảo được áp dụng phương pháp đường cơ sở quần đảo, nối liền các điểm ngoài cùng của các đảo xa nhất và các bãi đá lúc chìm, lúc nổi của quần đảo, với điều kiện là tuyến các đường cơ sở này bao lấy các đảo chủ yếu và xác lập một khu vực mà tỷ lệ diện tích nước đó với đất, kể cả vành đai san hô, phải ở giữa tỷ lệ số 1/1 và 9/1. Ngoài ra, quốc gia quần đảo được áp dụng quy chế pháp lý đặc biệt với vùng nước quần đảo (vùng nước được bao bọc bởi đường cơ sở quần đảo)

(11) Cơ quan quyền lực đáy đại dương là tổ chức có chức năng tổ chức và kiểm soát các hoạt động tiến hành trong Vùng nhằm mục đích quản lý các tài nguyên của Vùng vì mục tiêu di sản chung của nhân loại trên cơ sở Quy định về cơ cấu tổ chức, chức năng nhiệm vụ của Cơ quan quyền lực đáy đại dương được quy định chi tiết tại Phần XI và Hiệp định thực thi Phần XI của UNCLOS năm 1982

(13) Điều 33 Hiến chương Liên hợp quốc

(13) Nghĩa vụ trao đổi quan điểm được quy định tại Điều 283 UNCLOS năm 1982. Thời gian hợp lý được xác định theo hoàn cảnh của từng vụ, việc cụ thể

(14) Quy định tại Điều 287 UNCLOS năm 1982. Trong đó, Trọng tài thành lập theo Phụ lục VII và Trọng tài thành lập theo Phụ lục VIII đều là các trọng tài vụ việc (ad-hoc arbitration). Trọng tài thành lập theo Phụ lục VII có thẩm quyền chung với mọi loại tranh chấp liên quan đến việc giải thích và áp dụng UNCLOS năm 1982, còn Trọng tài thành lập theo Phụ lục VIII chỉ có thẩm quyền với các tranh chấp liên quan đến nghiên cứu khoa học biển

(15), (16) Quy định tại Điều 297 UNCLOS năm 1982

(17) Điều 244 UNCLOS năm 1982

(18) Cho tới nay, quá trình đàm phán đã được tổ chức tại 5 phiên họp toàn thể liên chính phủ. Xem: https://www.un.org/bbnj/

(19) Toàn văn Tuyên bố được lưu tại cơ sở dữ liệu của Liên hợp quốc về yêu sách biển của các quốc gia, https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/VNM_1977_Statement.pdf

(20) Điểm 2, Nghị quyết của Quốc hội nước Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam về việc phê chuẩn Công ước của Liên hợp quốc về Luật Biển năm 1982 ngày 23-6-1994

(21) Việt Nam nộp đệ trình khu vực thềm lục địa mở rộng phía Bắc tới CLCS vào ngày 7-5-2009, https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_vnm_37_2009.htm

(22) Đệ trình chung giữa Việt Nam và Ma-lai-xi-a về ranh giới thềm lục địa mở rộng được nộp vào ngày 6-5-2009, https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_mysvnm_33_2009.htm

(23) Hiệp định hợp tác nghề cá ở Vịnh Bắc Bộ giữa Chính phủ nước Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam và nước Cộng hòa Nhân dân Trung Hoa, năm 2000, http://biengioilanhtho.gov.vn/medias/public/Archives/head/Cac%20nuoc%20bien%20gioi/UBBG.Viettrung09.pdf

(24) Sau khi Việt Nam nộp đệ trình thềm lục địa mở rộng khu vực phía Bắc, Phi-líp-pin gửi Công hàm bày tỏ quan ngại thềm lục địa của Việt Nam có thể tạo ra chồng lấn với thềm lục địa của Phi-líp-pin. Tuy nhiên, cho tới nay, khu vực chồng lấn chưa được xác định cụ thể. Tương tự, thềm lục địa mở rộng của Việt Nam cũng có thể tạo ra khu vực chồng lấn với Bru-nây

(25) Văn kiện Hội nghị lần thứ tám Ban Chấp hành Trung ương khóa XII, Văn phòng Trung ương Đảng, Hà Nội, 2018, tr. 81

(26) Nhóm bạn bè UNCLOS là nhóm đầu tiên Việt Nam khởi xướng, đồng chủ trì vận động thành lập (cùng Đức) và tham gia nhóm nòng cốt (bao gồm 12 nước là Ác-hen-ti-na, Ca-na-đa, Đan Mạch, Đức, Gia-mai-ca, Kê-ny-a, Hà Lan, Niu Di-lân, Ô-man, Xê-nê-gan, Nam Phi và Việt Nam). Đến nay, tham gia Nhóm bạn bè của UNCLOS có 115 nước, đại diện cho tất cả các khu vực địa lý

(27) Xem: Phát biểu của Chủ tịch Phiên họp lần thứ 76 của Đại hội đồng Liên hợp quốc Áp-đun-la Sa-hít (Abdulla Shahid), United Nations, ngày 29-4-2022, https://www.un.org/pga/76/2022/04/29/40th-anniversary-of-the-adoption-of-the-united-nations-convention-on-the-law-of-the-sea-unclos/

Nguồn: https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/quoc-phong-an-ninh-oi-ngoai1/-/2018/826103/cong-uoc-cua-lien-hop-quoc-ve-luat-bien-nam-1982--bon-muoi-nam-vi-hoa-binh%2C-phat-trien-ben-vung-bien-va-dai-duong.aspx

![[Photo] Party Committees of Central Party agencies summarize the implementation of Resolution No. 18-NQ/TW and the direction of the Party Congress](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/27/1761545645968_ndo_br_1-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man receives Chairman of the House of Representatives of Uzbekistan Nuriddin Ismoilov](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/27/1761542647910_bnd-2610-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] The 5th Patriotic Emulation Congress of the Central Inspection Commission](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/27/1761566862838_ndo_br_1-1858-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)