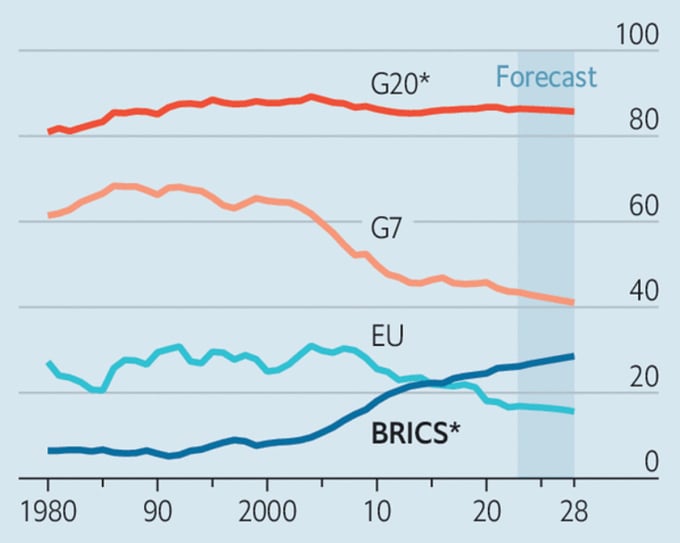

Accounting for 26% of global GDP and could reach 34% if expanded, but BRICS' weakness compared to the G7 is the large differences between its members.

In 2009, Brazil, Russia, India and China held the first summit of emerging economies on forming an economic bloc. South Africa was invited to join the following year, marking the completion of BRICS. At the time, analysts feared the bloc would soon rival the G7 (Britain, US, Germany, Japan, France, Canada and Italy).

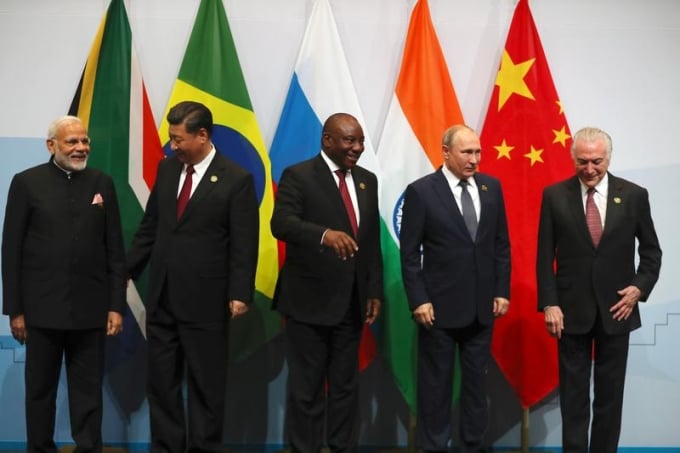

However, that has not yet come true, even though the BRICS's share of world GDP has increased from 8% in 2001 to 26% today. During the same period, the G7's share has decreased from 65% to 43%. On August 22, the 15th BRICS summit opens in Johannesburg, South Africa. The event brings together South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The summit will highlight how the bloc has emerged from the Ukraine conflict and rising tensions between the West and China. BRICS members, led by Beijing, are considering whether to expand the group, which some middle powers see as a good fit. More than 40 countries have signed up or expressed interest in joining.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Chinese President Xi Jinping, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Brazilian President Michel Temer at the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, July 26, 2018. Photo: Reuters

BRICS exists for a few reasons. It is a platform for members to criticize other institutions like the World Bank, the IMF and the UN Security Council for overlooking developing countries. India's foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, said the "concentration" of global economic power was "putting too many countries at the mercy of too few."

Membership also gives countries prestige. Brazil, Russia and South Africa have grown GDP by less than 1% annually on average since 2013 (compared to around 6% for China and India). Investors are not particularly interested in Brazil or South Africa’s prospects, but being the only Latin American or African country in the group gives them continental clout.

The bloc also provides support when its members are isolated. Jair Bolsonaro, former president of Brazil, turned to BRICS after his ally, Donald Trump, left the White House. Russia needs BRICS more than ever these days. At a meeting of foreign ministers, the Russian ambassador to South Africa told reporters that they joined the bloc to “make more friends.”

Russia would achieve this if China succeeded in bringing in more developing countries. The reason is almost Newtonian: the US rallying of Western allies forces China to seek a counter-balancing response through BRICS.

Share of global GDP of blocs over time. Source: Economist

With the world's second-largest economy, there is no other bloc that can compete with the G7. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization is largely European and Asian, and the G20 is too dominated by Western members. Therefore, BRICS is a good choice. A Chinese official compared Beijing's desire for a "big family" of BRICS countries to the "small circle" (i.e., a small number of large countries with dominant power) of the West.

BRICS has not yet announced an official candidate for admission. However, the Economist has counted 18 prospective countries, based on three criteria: having applied to join, being named as a candidate by South Africa (the host of this conference); being invited to the 15th conference as a "friend" of the bloc.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are keen to recalibrate their relationship with the US and move closer to China. Bangladesh and Indonesia, like India, are populous Asian countries that want to be shielded from Western criticism on political issues. Argentina, Ethiopia, Mexico and Nigeria are all among the largest countries on their continents.

In the unlikely event that all 18 countries were admitted, the population would increase from 3.2 billion (41% of the world) to 4.6 billion (58%), compared to 10% for the G7 members. The economic share of the “Big BRICS” would increase to 34%, still behind the G7 but double that of the EU. However, China would still be the mainstay, accounting for 55% of the 23 countries’ output (while the US accounts for 58% of the G7).

Even as membership is still being discussed, the bloc is tightening its existing ties. In addition to the annual summit of the big players, there are increasingly meetings of academics, companies, ministers, ruling parties and think tanks from members and countries friendly to them. “These meetings are often dull, but they help officials globalize their relationships,” argues Oliver Stuenkel of the Getulio Vargas think tank in Brazil.

The BRICS have also made more serious efforts. They have established two financial institutions, which the Russian Finance Minister once described as mini-IMFs and World Banks. One example is the mini-World Bank, the New Development Bank (NDB). Launched in 2015, it has lent $33 billion to nearly 100 projects. Since it is not limited to BRICS membership, the NDB has attracted Bangladesh, Egypt, and the UAE. Uruguay will soon be admitted.

An expanded "Big BRICS" would be a challenge to the West but not a mortal threat, according to the Economist .

Because this bloc has internal problems. While China wants to expand, Russia is economically weak, and Brazil, India and South Africa are skeptical. Unlike the G7, these five members are not homogeneous, differing greatly in politics, economics and military, so expansion will deepen the differences. That means, although the bloc could threaten the Western-led world order if it were larger, it would be difficult to replace it.

Consider the economic differences. The poorest member, India, has a per capita GDP of just 20% of that of China and Russia. Russia, a key OPEC+ member, and Brazil are net oil exporters, while the other three are dependent on imports. China actively manages its exchange rate, while the other four intervene less.

All of this complicates the bloc’s efforts to change the global economic order. The idea of a common BRICS reserve currency is stymied because no member would give up the power held by its central bank. They often defend their own power in other economic institutions.

The NDB has had a slow start. Its total lending since 2015 is only a third of what the World Bank has committed to in 2021. The World Bank is more transparent and accountable, notes Daniel Bradlow of the University of Pretoria in South Africa. The fact that the NDB issues loans mainly in dollars or euros somewhat undermines members’ claims that they are trying to reduce the strength of the greenback.

Internally, India may be a significant dissenting voice in some decisions. In the early days of the bloc, India thought that with Russia’s help, it could better deal with China, according to Harsh Pant, vice president of the Delhi-based think tank Observer Research Foundation.

But now Russia is relying on China. And India worries that some candidates, like Cuba and Belarus, could become mini-Russians, too, in the service of China. According to the Economist , India is racing China to take leadership of developing nations. But it also doesn’t want to be a troublemaker. So it’s treading carefully, wanting to discuss the eligibility criteria for new members more thoroughly.

Phien An ( according to The Economist )

Source link

![[Photo] Many dykes in Bac Ninh were eroded after the circulation of storm No. 11](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/15/1760537802647_1-7384-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Conference of the Government Party Committee Standing Committee and the National Assembly Party Committee Standing Committee on the 10th Session, 15th National Assembly](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/15/1760543205375_dsc-7128-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] The 18th Hanoi Party Congress held a preparatory session.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/15/1760521600666_ndo_br_img-0801-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)